7 essential strategies for adopting new technologies

- The integration of transformative new technology can lead to a substantial competitive advantage — but done poorly, it can be costly and ineffective.

- From “nudge theory” to agile iteration, there are key steps all companies should consider when piloting new tech.

- For anyone thinking about tech integration, the selective wisdom of Steve Jobs and Jeff Bezos is invaluable.

This is a boom time for radical new tech. Companies can deploy drones, genomics, augmented reality, generative AI, consumer robotics, and 3D printing with relative ease. In theory these technologies are a blessing — each innovation is a chance to boost efficiency, to dream up new business models, and to find a competitive advantage over rivals. But new tech is a double-edged sword. Integration can be expensive and perilous: Mess up the adoption and jobs are on the line.

Fortunately, there are tried and tested principles to smooth the process of adopting any new technology. These seven essential concepts can help your company avoid common pitfalls, and fully benefit from the most transformative era in the history of human enterprise.

#1. Overcome inertia with “nudge theory”

Companies have an in-built resistance to adopting new technology. Senior managers are wary of punishment if the implementation goes wrong. The benefits may be hard to quantify. Research published by the Harvard Business Review offers ways for advocates to galvanize reluctant senior managers.

By applying the principles of “nudge theory,” says the research, it’s possible to persuade holdouts. “Many of these techniques play on core facets of human programming, such as the human fear of missing out. For example, comparing commercial progress or digital strategy with competitors can be an effective method to highlight the cost of inertia. It’s also important to make it clear that tech-driven strategy is the new standard. Instead of asking, ‘Do you want to adopt technology?’ the question should be, ‘Which technology do you want to adopt?’”

The study advises companies to imagine scenarios in which the technology is not adopted. Schedule regular meetings to discuss the initiative, so it becomes an unavoidable topic of conversation; talk to managers one by one, to prevent groupthink; and avoid binary framing, in which a new technology is all or nothing, as this prospect can intimidate conservative thinkers.

Making the business case alone may not be enough to generate support — in which case, additional time may be required. “Humans take time to change and so it takes a much longer-term approach to shift their mindset.”

#2. Focus on the consumer

Steve Jobs was used to being insulted. One attack stung more than most. During a Q&A session in 1997 he was asked by a furious developer why he had discontinued a much admired programming language called OpenDoc in favor of the supposedly inferior Java.

“You can’t start with the technology and try to figure out where you’re going to try to sell it. I’ve made this mistake… and I’ve got the scar tissue to prove it.”

Steve Jobs

His reply is now folklore: “One of the things I’ve always found is that you’ve got to start with the customer experience and work backwards to the technology. You can’t start with the technology and try to figure out where you’re going to try to sell it. And I’ve made this mistake, probably more than anybody else in this room. And I’ve got the scar tissue to prove it. As we have tried to come up with a strategy and a vision for Apple, it started with ‘What incredible benefits can we give to the customer? Where can we take the customer?’ Not starting with, ‘Let’s sit down with the engineers and figure out what awesome technology we have and then how are we going to market that.’”

The counterintuitive implication here is clear: Don’t build outwards from the tech, but backwards from your consumer.

#3. Test in a defined “use-case”

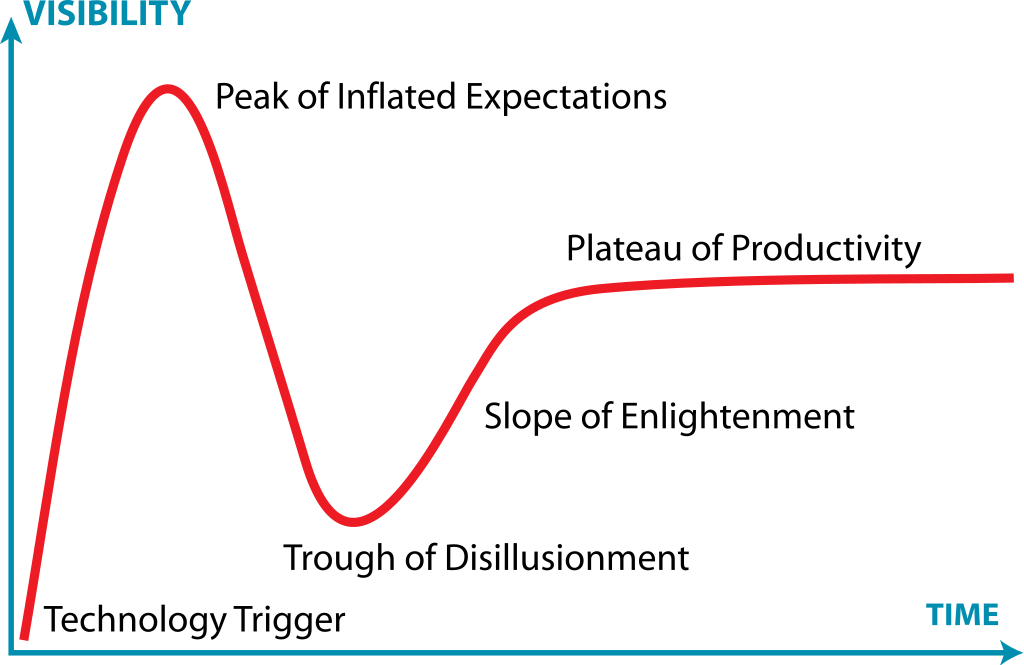

One option for evaluating any potentially transformative new technology is to apply the Gartner Hype Cycle, designed by the eponymous advisory company to answer one essential question: Is the hype real?

The Gartner Hype Cycle graphically represents the various phases through which technologies evolve — from “technology trigger” to “plateau of productivity.” It’s no hard-and-fast solution but it does highlight several important considerations, including this one: Timing is always crucial. Test a technology too early, for example, and it may fail due to immaturity, not lack of potential.

This potential roadblock has been examined by professor Torbjorn Netland, Head of Chair of Production and Operations Management (POM) at ETH Zurich. Netland studied Ikea’s use of autonomous drones to stock-take in warehouses. “If Ikea [had] tested drones at the peak of hype in 2016 their test would have failed. The drones were too expensive and not robust.” The key here, he says, is to test the new technology in a defined use-case that addresses a real problem, then iterate, and evaluate. Over time, IKEA successfully identified the benefits and drawbacks of the drones while the drone vendors iteratively improved the technology to fit IKEA’s use case.

#4. Keep going despite lack of information

All management decisions are made in a fog of uncertainty — but new technology is in a class of its own when it comes to lack of clarity. You’re guaranteed to be missing all the performance data and benchmarks you’ll need, but that should never be a barrier to progress. The secret is to keep moving.

“If you’re good at course correcting, being wrong may be less costly than you think, whereas being slow is going to be expensive for sure.”

Jeff Bezos

Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon, put it this way: “Most decisions should probably be made with somewhere around 70% of the information you wish you had. If you wait for 90%, in most cases, you’re probably being slow. Plus, either way, you need to be good at quickly recognizing and correcting bad decisions. If you’re good at course correcting, being wrong may be less costly than you think, whereas being slow is going to be expensive for sure.”

#5. Know your RoI timeline

What’s your return on investment timeline? Successful adoption of a new technology demands this information: Without it, you can’t budget for the time needed.

For example, at some point in the not-too-distant future, quantum computers could revolutionize many sectors, from battery technology to statistical forecasting and drug discovery. Here’s the thing: Commercially widespread and useful quantum computing is not here yet, and the hardware is inherently fragile, awaiting the breakthroughs required for reliable iteration. Success is by no means guaranteed. Consequently, investing in quantum computing is a long-term game, so the market participants are positioned to cope with prolonged development costs.

Infleqtion, maker of the Hilbert quantum processor, works with NASA and DARPA, the U.S. military research arm. This funding model, supplemented by patient early stage investors such as Innovate UK, means Infleqtion can focus on the long-term development of Hilbert. If you know your RoI timeline you can conserve cash to last the course. If your projections are too short-term you’ll run out of resources before payback.

#6. Iteration, iteration, iteration

New technology is never complete. There’s always an upgrade. In his book The Evolution of Everything, science writer Matt Ridley chronicles how inventions are the result of cumulative improvements, and almost never big-bang leaps. So it’s not just Thomas Edison and his thousands of experiments to create a light bulb, but decades of subsequent improvements, via halogen, neon, and organic LEDs. A basic concept can remain stable while performance soars — for example, a 5G mobile phone network is up to 200,000 times faster than a 2G data connection.

At companies such as Google, Spotify, Microsoft, and eBay, the dominant philosophy is “cloud native” software. A main feature is the ability to update code without going offline, so individual improvements can be tested as and when they are ready. At one point Amazon revealed it deploys new code every 11.6 seconds. In this way, the software evolves over time, rather than in big leaps.

#7. Fully integrate and adapt

Even if your implementation of a new technology is correct, the financial metrics may move in the wrong direction, temporarily. Researchers at the University of Cambridge studied industry data from the UK and 24 other European countries between 1995 and 2017, and found that at low levels of adoption, robots have a negative effect on profit margins. At higher levels of adoption, robots can help increase profits.

“Intuitively, we thought that more robotic technologies would lead to higher profit margins, but the fact that we see this U-shaped curve instead was surprising,” said co-author Dr Philip Chen.

“Initially, firms [adopt] robots to create a competitive advantage by lowering costs,” said his co-author Professor Chander Velu. “But process innovation is cheap to copy, and competitors will also adopt robots if it helps them make their products more cheaply. This then starts to squeeze margins and reduce profit margin.”

The research suggests that only after the technology was fully integrated into the business model could its power to develop new products — and drive profits — be fully exploited. The bottom line: Be agile and adapt your business model concurrently with the adoption of new technology.