Mother of Invention

Wouldn’t it be ironic if the origin of big, bad, brawny Jackson Pollock’s drip and splatter paintings were a wifely homemaker, mother, and grandmother from Brooklyn? And wouldn’t it be true? Gary Snyder Fine Art in New York City presents the work of Janet Sobel, whose early 1940s drip paintings inspired Pollock to explore the possibilities of that style and essentially found the Abstract Expressionist school. Rather than rise likewise into fame and fortune, Sobel moved with her husband and family to Plainfield, New Jersey, and enduring obscurity. Gary Snyder brings Sobel back to the big city and the big stage she deserves.

Born in the Ukraine in 1894, Sobol emigrated to America in 1908, married, and raised five children. She didn’t pick up a brush until the age of 43. With no training, she developed her unique style, often labeled as “outsider” or “folk” art, of painting simple figures and covering them with a rhythmic pattern of dripping paint. Max Ernst and Andre Breton embraced her as a fellow surrealist. Peggy Guggenheim included Sobol in her Women show at her Art of This Century gallery in 1945. At a 1946 one-person show at Guggenheim’s space, Pollock and critic Clement Greenberg saw Sobel’s work together. “Pollock (and I myself) admired these pictures rather furtively,” Greenberg later confessed. “Later on, Pollock admitted that these pictures had made an impression on him.” Pollock took that impression and leapt into notoriety, while Sobel’s husband packed the car for Plainfield, a fate she dutifully accepted. The rest, as they say, is history.

Not until an exhibition at Gary Snyder Fine Art in 2003 was Sobel’s work seen by the public again. Scholars have since tried to resurrect the “mother” of Abstract Expressionism, but sadly, Sobel remains a well-kept secret. Although an outsider from the academy, Sobel was embraced by many critics during her time in the spotlight. In 1944, educational philosopher John Dewey wrote of Sobel’s work in his characteristically florid style, “The quality I myself seem to feel most vividly is that of the interblending of the abundant life of vegetation with the sparser life of human beings in a kind of brooding maternal wholeness.” That “brooding maternal wholeness” is what endures in Sobel’s paintings and drives exhibitions such as this in an attempt to give that different voice a chance to be heard at last.

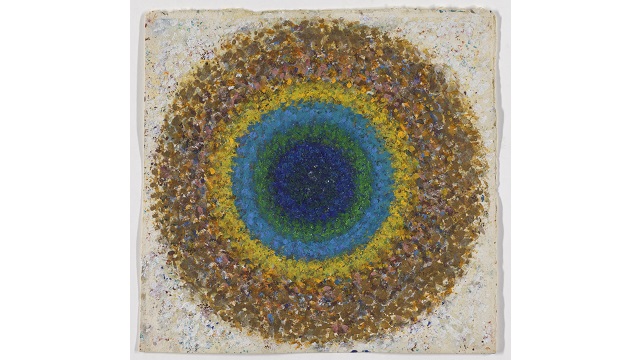

When you look at works such as Sobel’s untitled 1944 painting shown, the temptation is not to see the vegetation like drip pattern blending with the figure as much as to see the dripped paint obscuring the figure—just as circumstances conspired to obscure the figure of Janet Sobel for more than half a century. Gary Snyder Fine Art’s exhibition allows us to see the figure behind the technique again—not by parting the lattice-like patterns like a curtain, but by illuminating the scene for us to peer through to the artist herself.

[Image: Janet Sobel, Untitled (JS-032), c. 1944, oil on caning]

[Many thanks to Gary Snyder Fine Art for providing me with the image above and press materials for Janet Sobel at Gary Snyder Project Space: Drip Paintings and Selected Works on Paper, running now through February 27, 2010.]