What is a villain?

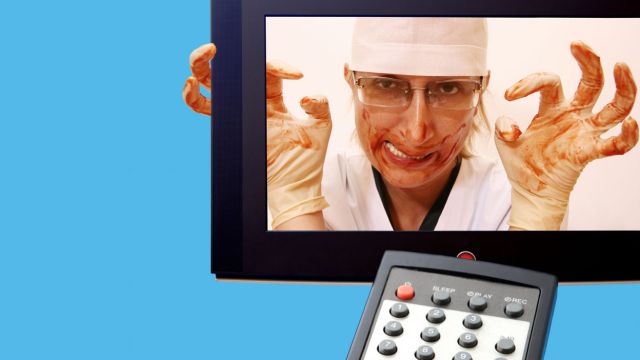

Image courtesy of Shutterstock

“The villain,” say Chuck Klosterman in his rambling, rollicking, yet oddly coherent book I Wear The Black Hat, “is the person who knows the most but cares the least.” This, then, is a fascinating book about everybody’s temptation by villainy, a subject about which we know the least and care the most.

The book forms its definition of villainy by tracing the theme from Newt Gingrich to Darth Vader to Snidely Whiplash to O.J. Simpson to Bill Clinton, passing through The Eagles, Machiavelli, Charles Bronson, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and more on the way (including a somewhat abortive attempt to include Hitler).

Klosterman, who writes the column, The Ethicist for The New York Times, and who has written several other books, seems to be obsessed with pop culture to the point of compulsion, but the immediacy and informality of his style brings the reader in on that compulsion too. The book, which, if I’m honest, I did not have high hopes for, turns out to be as much a study in a sort of meta-self-exploration as it is about villainy.

It’s greatest success is that, in discussing a theory of an abstraction, villainy, the treatment via the many personal fixations and feelings of the author does not get in the way. In fact, this treatment magnifies the reader’s ability to check the book’s suppositions against his own intuitions, since Klosterman’s total inability to ignore his intuitions becomes infectious.

Klosterman is so comfortable switching back and forth from the intellectual realm to the popular realm that he does his readers the enormous service of forcing them to reject the divide between the intellectual and nonintellectual completely.

For example, on one page he offers this criticism of the ubiquity of espoused relativism in our culture: “It’s possible that context doesn’t matter at all. It seems like it should matter deeply, because we’ve all been trained to believe ‘context is everything.’ But why do we believe that? It’s because that phrase allows us to make things mean whatever we want, for whatever purpose we need.”

A mere two pages later he is positing, with just as much seriousness, that “The most villainous move any person can make is tying a woman to the railroad tracks.”

Klosterman was prompted to write I Wear the Black Hat, because, as the title suggests, he finds himself identifying with and rooting for the villain in most situations. As he describes it in terms of Star Wars, little boys (and, let’s be honest, this is a book that is largely aimed at a male audience) love Luke Skywalker, but as they get older they begin to prefer Han Solo, who acts like a bad boy but is on the side of good, and eventually find themselves most compelled by Darth Vader, villain extraordinaire.

That seems like a fair assessment of the general feelings towards those characters to me (and reflects my own experience). So the central question the book is left with is this: Why do we like the people we, ourselves, identify as bad?

The book offers a partial answer to the question. Those who know the most and care the least have a level of confidence that looks liberating, and that liberation is attractive. The amorality that villains get to have by “wanting to be bad” looks easy.

So the question that the book is valuable for raising turns out not to be “Do we see villainy in ourselves?” It turns out to be “Do we want to?”