Scientists find a new way to measure gravity

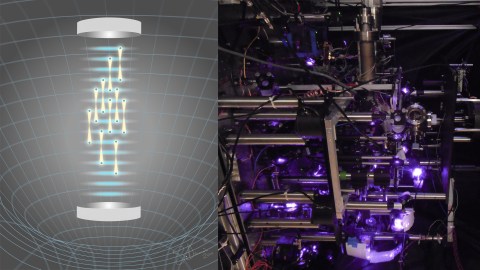

Credit: Sarah Davis / Victoria Xu

- Scientists use lasers that suspend atoms in air to measure gravity.

- This method can be more precise and allow for gathering of much more information.

- Portal devices using this technique can help find mineral deposits and improve mapping.

You drop something and it falls. That’s how you know there is gravity, right? Scientists at the University of California, Berkeley, improved upon this age-old test to find a new and potentially more useful way to measure gravity using lasers suspending atoms in midair.

The usual approach to measuring gravity involves making something fall, preferably in a long shielded tube or tower, and then measuring it as it flies by with an instrument. While this classic method connects to our everyday experience of gravity, it has limitations. For one, the opportunity to understand gravitational effects is very brief during such a test. There are also other forces, like magnetic fields, at play, possibly affecting the results.

The new technique developed by a team of researchers, led by physicist Victoria Xu, doesn’t rely on making anything fall. Instead it pinpoints the differences in atoms in a superposition state.

Superposition is the physics principle that says a system can be in multiple states until it’s measured.

What the researchers figured out is a process that starts by releasing a cloud of cesium atoms in a small chamber. Then they used flashing lights to split some of them into superposition states. Once the atoms were taken apart in this way, lasers were employed to keep them in fixed positions.

One atom in each pair was suspended a few micrometers higher than the other. This allowed the scientists to measure the wave particle duality of each atom’s wave as it was being affected by gravity.

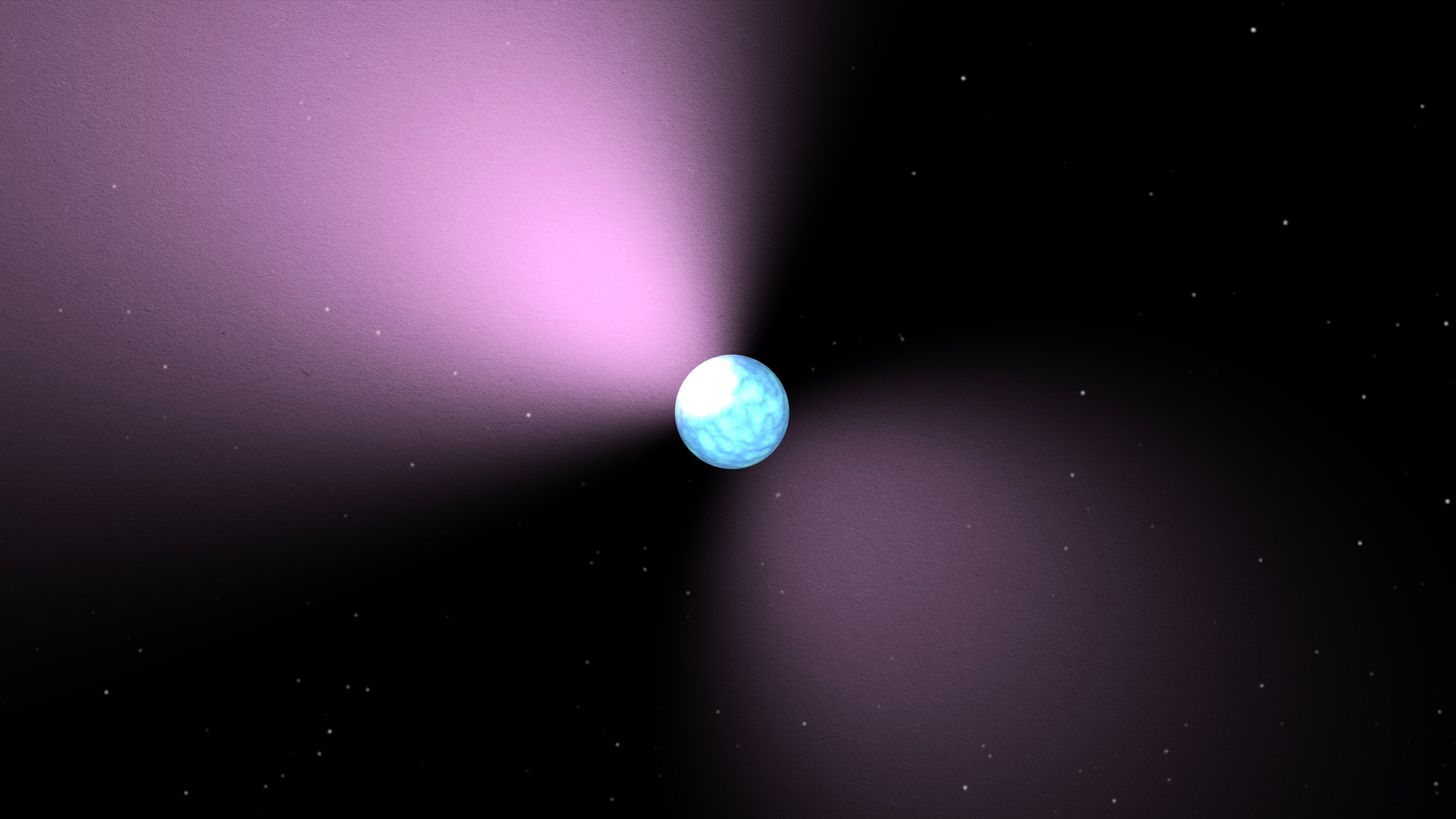

“Atoms in a spatially-separated quantum superposition are suspended against Earth’s gravity, using the standing wave formed by an optical cavity. “

Wave particle duality is the quantum mechanics idea that every particle can act as a particle or a wave.

Measuring differences in duality between the atoms in a pair, with each one being at a varying distance from Earth, allowed the researchers to quantify the effects of gravity on the atoms.

The advantage of this technique is that it can potentially help gather a lot of new information, with implications for a wide range of fields, even the search for dark matter. Not having the atoms zipping through the air aids in the collection of significantly more precise measurements of gravity as well as the gravitational attraction between objects and more.

It is also easier to protect these much smaller measuring devices from interfering magnetic fields.

Another cool thing – this type of approach makes it easier to create portable gravity-measuring devices. That way they can be taken to different places on Earth to look for mineral deposits and for improved mapping.

“Laser light (purple) shines into our ultra-high vacuum chamber to laser-cool atoms to less than half a millionth of a degree above absolute zero. A pair of mirrors mounted inside the vacuum chamber enhance flashes of light which kick, suspend, and interfere the atoms. “

The study’s co-author Holger Müller laid out some of the benefits:

“Let’s say you don’t want to measure the gravity of the entire Earth, but you want to measure the gravity of a small thing, such as a marble,” he said to Science News. “We just need to put the marble close to our atoms [and hold it there]. In a traditional free-fall setup, the atoms would spend a very short time close to our marble — milliseconds — and we would get much less signal.”

The initial reviews on the study were positive, with physicist Alan Jamison of MITcalling it “very impressive.”

Check out the new study “Probing gravity by holding atoms for 20 seconds” in the journal Science.