When prairie dogs brought monkeypox to America

- Monkeypox, a relative of smallpox, is endemic in West and Central Africa.

- Currently, there are outbreaks of monkeypox in several countries around the world.

- In 2003, prairie dogs caused a rash of cases across the Midwest.

For Molly Hinshaw, the question was obvious: Was there a prairie dog involved?

In 2003, Hinshaw was a dermatology resident doing her rotation at the Medical College of Wisconsin’s Froedtert Memorial Lutheran Hospital in Milwaukee. One day, she told Big Think, a patient had arrived presenting unusual skin lesions.

She had recently seen a presentation at the University of Wisconsin-Madison from Erik Stratman, a dermatologist at Marshfield Clinic. In his lecture, Stratman described a mystery case that had come into the clinic: a mother and daughter who had fallen ill and presented with skin lesions caused by a pathogen that their typical tests failed to reveal. A lesion from the mother’s hand had been biopsied and sent to Stratman’s colleagues to see if they could identify the culprit. Thanks to a call mid-presentation from a colleague who caught the virus on camera (with an electron microscope), Stratman was able to add a big reveal to his talk: the cause was an unidentified orthopoxvirus.

As Hinshaw had suspected, the patient confirmed contact with a prairie dog. So, she immediately contacted Stratman to let him know the news: His mystery virus wasn’t just at Marshfield.

Modern monkeypox

Still in the grips of SARS-CoV-2, the world is finding itself faced with yet another rapidly spreading outbreak, this time of a heretofore geographically contained pathogen, monkeypox. As of June 2, there have been 643 confirmed cases of monkeypox outside of its usual stomping grounds in West and Central Africa. The virus has been detected in at least 30 countries, including much of Europe, Australia, Canada, and the U.S.

Typically, monkeypox is transmitted through contact with broken skin, mucosal membranes like the eyes, nose, and mouth, or the respiratory tract. It may spread from infected animals by bites, scratches, and butchering. It can also be caught from materials contaminated by lesions, like bedsheets.

So far, most cases have been detected in young men who self-identify as having sex with men, leading experts to speculate that the close contact inherent in sex could be a driver of the outbreak. Large respiratory droplets are believed to be the primary mechanism of human-to-human transmission. Unlike the aerosolized transmission of SARS-CoV-2, these larger droplets don’t travel far or float long, meaning close contact is likely needed. There is currently no evidence of sexual transmission per se through semen or vaginal fluid.

As of June 2, the U.S. has 21 confirmed cases of monkeypox. But this isn’t our first rodeo with the virus, and certainly not our largest (yet). Because in 2003, a chain of transmission spanning Ghana to Texas to Illinois and ending with pet prairie dogs brought monkeypox all across America.

A strange family tree

When monkeypox first arrived in Wisconsin, it only had been two years since 9/11 and the anthrax attacks, Janet Fairley tells Big Think. So, when these strange lesions showed up at Froedtert, there was fear that someone had weaponized one of our greatest and most ancient foes: smallpox.

That is why Fairley had been called in to take a look. She had been vaccinated against it. Now the head of dermatology at the University of Iowa, Fairley and her colleague Mary Beth Graham examined the patient and took biopsies of his lesions, sending them off to the CDC, which identified monkeypox.

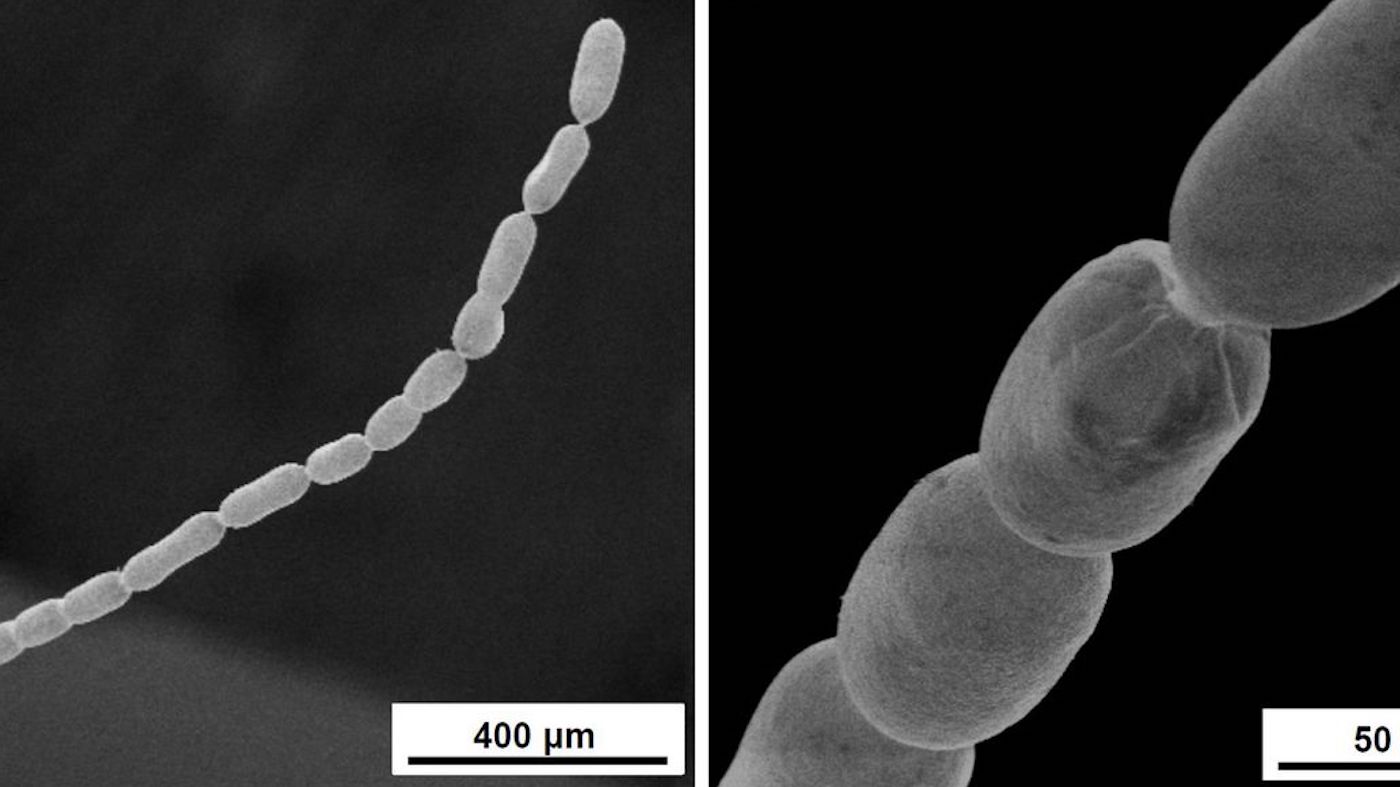

Monkeypox is an Orthopoxvirus, a genus of large, complex, oblong viruses with distinctive dumbbell-shaped cores that includes two notable relatives: Variola, the cause of smallpox, and Vaccinia, a virus of mysterious provenance used in smallpox vaccines. Monkeypox is now considered the most significant Orthopoxvirus infection of humans, considering that its fearsome cousin, smallpox — so deadly it was worshiped in multiple cultures as a deity — was eradicated from the wild.

According to the ECDC, the virus was first isolated from monkeys being used as subjects in polio vaccine research, which lent the virus its misleading name. While it can cause disease in monkeys, the actual animal that plays host to the virus is still unknown, with rodents being prime suspects.

In 1970, the virus was spotted in humans for the first time in the Democratic Republic of the Congo nine months after smallpox had been wiped out in the region. Because we no longer vaccinate against smallpox, our bodies lack immunity to the disease — and possibly cross-immunity to monkeypox, as well. Perhaps this is why monkeypox cases have risen markedly over the past two decades. The first cases reported outside of Africa occurred in 2003.

From West Africa to Wisconsin

Determining the chain of transmission — the path a virus takes through a community — hopefully all the way back to the very first infection is the job of epidemiologists. They use this information not only to figure out where an outbreak came from, but to find other potentially exposed people in an attempt to snuff out the outbreak.

According to an article in the New England Journal of Medicine, whose authors included the aforementioned Stratman, Fairley, and Graham, the 2003 outbreak unfolded in this way: The patient in Milwaukee, a meat-inspector and part-time exotic animal dealer, had recently sold prairie dogs to the mother-daughter duo who also had fallen ill.

The dealer, in turn, had purchased the animals from a Chicagoland distributor, whose shipment of prairie dogs — which arrived from Texas — was kept in close proximity to giant Gambian rats, the Associated Press reported at the time. A subsequent 2004 journal paper tied this all together, pointing to Ghana as the original source of the Gambian rats. By the time the outbreak ended, there were 72 confirmed or suspected monkeypox cases across several U.S. states.

Thus, epidemiologists were able to reveal a chain stretching back in time from Wisconsin to West Africa. “There was nothing I had seen more like Sherlock Holmes in today’s world than the Wisconsin Public Health epidemiology team,” Stratman says.

To prevent further spread of monkeypox, at least 30 people were given the smallpox vaccine. The outbreak led to an African rodent importation ban that stands to this day.

The current fight

There would not be another monkeypox case in the U.S. until 2021, when two separate cases were found in travelers coming from Nigeria, where the virus is endemic. But now, public health officials are faced with the largest outbreak of the virus since 2003. Thankfully, our arsenal of weapons has expanded since then. Most importantly, there is now a vaccine officially approved for monkeypox. We should not expect monkeypox to shatter society like COVID did.