Spillback: How often do humans give animals diseases?

- COVID-19 has provided a stark example of animals passing a dangerous disease to humans, an event called “spillover.”

- Less understood and studied is the phenomenon of “spillback,” when humans pass diseases to animals.

- A research team discovered 97 such cases in the scientific literature and warned that more research and monitoring are needed to protect wildlife from humans and vice versa.

Zoonosis: Much of humanity has grown intimately familiar with this term over the past two years. It describes an “infectious disease caused by a pathogen that has jumped from an animal to a human.” After originating in some creature, likely a bat, and then potentially infecting an intermediary species, perhaps a pangolin, raccoon dog, mink, or fox, SARS-CoV-2 leapt into humans and spread across the world, causing the disease COVID-19. We are the virus’ primary hosts now. Thanks, wild animals!

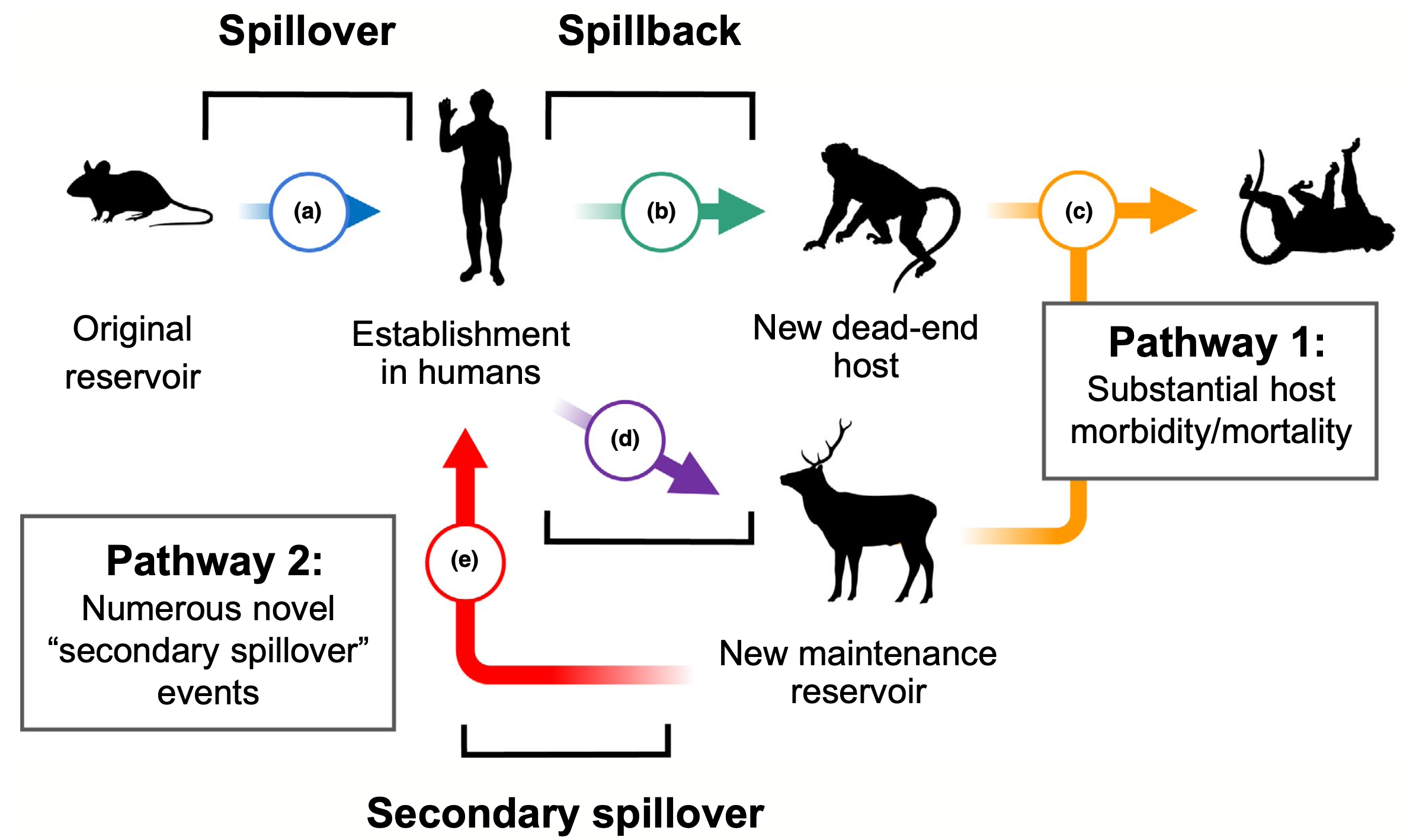

But infection is a two-way street. Yes, pathogens like coronaviruses can “spillover” from animals to humans, but they can also “spillback” from humans to animals.

Spillback

This concept was the focus of a recent review published in the journal Ecology Letters. With all the attention zoonoses have been receiving of late, an international team of experts in ecology, microbiology, and infectious disease sought to shine a light on when and how humans pass diseases to animals, a process called reverse-zoonosis or spillback.

Reviewing the scientific literature, they found 97 documented instances. Roughly half of these occurred in captive settings like zoos, where humans are regularly in contact with wild animals and are far more likely to notice their maladies. Sixty percent of the total cases were in non-human primates like chimpanzees and gorillas, which are closely related to us and thus more susceptible. Elephants, long-lived birds, hoofed animals, and rodents were some of the other creatures affected.

Obviously, the 97 cases were limited to just those that had been scientifically recorded, so they unquestionably constitute an undercount of all human-to-animal disease transmissions. For example, five snow leopards have died from COVID-19 in U.S. zoos, but their spillback cases were reported in the popular press, not the scientific literature, and thus did not make the researchers’ count. All of these big cats likely contracted the disease from their caretakers.

Moreover, a significant amount of spillback could occur in the wild as humans interact with animals, but we may simply not notice, perhaps due to a lack of monitoring or because human-to-animal infections rarely cause noticeable effects. Squirrels, for example, are known to transmit numerous viruses to humans, but there isn’t any mention in the scientific literature of humans passing pathogens to them. Surely, considering how often we interact with these ubiquitous rodents, we have infected them with something.

Spillover to spillback to spillover again

When we do pass our diseases to animals, it is often through one of three routes: wildlife spending time near our copious, concentrated sewage and runoff; wildlife picking up any parasites living on us or in us; or wildlife breathing in one of our respiratory pathogens.

What happens after that varies. A spillback could trigger a massive die-off, putting the animal population at risk. Alternatively, the animal could become a reservoir for the pathogen, where the pathogen could potentially mutate and perhaps even spillover back into humans. We have already passed SARS-CoV-2 into mink populations in Spain and white-tailed deer in North America. Scientists are concerned that, at some point, these animals could seed us with a new form of the virus that evades our hard-earned immunity.

As the COVID-19 pandemic has made clear, monitoring and researching zoonotic disease is immensely important, especially as Earth grows more crowded and its denizens more connected. “Ongoing increases in human population density, epidemic and pandemic risk, human-wildlife contact, and anthropogenic stressors on animal health stand to drive up the rate of human-to-wildlife pathogen transmission over the coming decades,” the researchers warn.