6 great books with wildly unreliable narrators

- Unreliable narrators — characters whose presentation of a story is marked by biases or outright falsehoods — play pivotal roles in many celebrated novels.

- Such narrators can distort reality, often leading to unexpected twists, challenging readers to decipher the true nature of events.

- From Gone Girl to Lolita, explore some of literature’s most compelling narratives, shaped by the intriguing and complex device of unreliable narration.

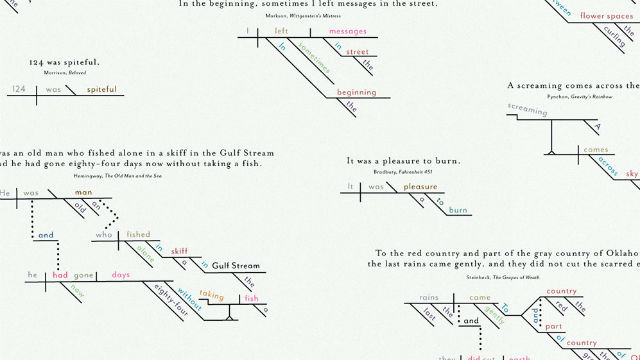

Some readers tend to accept that everything the narrator says is true. This may be the case in novels where the narrator is an omniscient being floating high above the action. But when the story is told from the first-person perspective, it’s often a mistake to think that the narrator is describing reality in a fair and accurate manner, as if they lack the kinds of biases, blind spots, and not-always-respectable motivations that most of us possess.

Here, we look at six books where you’d do well to take the narrator’s tale with a grain of salt. Several of these works are extremely controversial. This is partly due to the ill-advised tendency to presume that the author is endorsing everything the narrator says, even though usually the opposite is true. Be careful if you want to avoid spoilers; being on the list is a bit of a spoiler in itself.

A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess

“What’s it going to be then, eh?”

A dystopian black comedy disowned by its author and made into an (in)famous film by Stanley Kubrick, A Clockwork Orange is narrated by a 15-year-old lover of classical music, “milk-plus,” and “ultraviolence” known as Alex. The events of the novel — which explores themes of free will, maturity, and moral responsibility — are told from his perspective.

This narrative choice is part of what has made the book so infamous. Alex enjoys his crimes, is incredibly smug about his actions, and sometimes portrays himself as a victim. In one disturbing scene involving a sexual assault — a scene that was actually toned down for the film — it is initially difficult to tell what is going on because Alex buries the extent of his heinous crimes under slang and a nonchalant attitude.

If his viewpoint is taken as objective, the novel can appear to glorify the violence and destructive tendencies it condemns. This isn’t what was intended by the author, of course. It’s a fact that’s easier to pick up on when the book’s (often-cut) final chapter is included, in which Alex matures and forgoes his life of violence. But even without it, the book is a fascinating dive into a worldview of violence, drugs, and Beethoven through the eyes of somebody who fully embodies it.

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest by Ken Kesey

“This is what I know. The ward is a factory for the Combine. It’s for fixing up mistakes made in the neighborhoods and in the schools and in the churches, the hospital is.”

Another book with an arguably more famous movie, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is the story of what happens in an Oregon mental hospital ward when a nonconformist criminal feigns madness in hopes of getting out of chain-gang work. He quickly upends the ward’s routine and earns the ire of one of the great villains of American literature: the tyrannical Nurse Ratched. The novel explores themes of conformity, mental health, and how societal pressure can be as incontrovertible as law.

Unlike the film version, the novel is told from the perspective of one of the hospital’s residents, Chief Bromden. Also unlike the film, this version of the Chief is explicitly suffering from schizophrenia and depression. His narration varies between descriptions of events grounded in facts and sections that are obviously hallucinations. The former includes descriptions of the abuses inflicted on the mentally ill and American Indians. The latter includes the hospital staff “curing” Santa Claus, visions of oozing slime, and the ward’s walls opening up to reveal a vast slaughterhouse.

By the novel’s end, it is easy to wonder what happened and what did not happen. However, it is clear that something is happening, which makes it all the more frightening. The fact that many of the abuses noted in the book really took place and were based on Kesey’s experiences in MK-ULTRA adds to the horror.

Life of Pi by Yann Martel

“If you stumble at mere believability, what are you living for? Isn’t love hard to believe?”

Life of Pi is a 2001 novel by Yann Martel. Unlike many works featuring unreliable narration, this book begins by noting that what follows is mostly fiction. The story that follows examines the relativity of truth, religion, and absurdity.

The novel follows a young Indian boy named Pi as his family departs India for a new life in Canada. The ship they are taking goes down in a storm, leaving Pi trapped in a lifeboat alongside several animals. Among them is a 450-pound tiger named Richard Parker. What follows is a story of how Pi hopes to get out of this situation and how the events affect his religious worldview. Along the way, they meet an army of meerkats, cannibalistic plants, and a zebra with a broken leg.

Looking back on the story’s events, several characters question not only what really happened, but discuss what that even means. No matter what “really” happened in that lifeboat, the result is an excellent read.

Arabian Nights

“Quoth the bird, “I tell thee but what I saw and heard.””

One Thousand and One Nights, commonly referred to as Arabian Nights, is a collection of short stories from the Golden Age of Islam. While many editions of the work exist, they all share the common element of being framed as a series of stories told by Scheherazade, a clever young woman and able storyteller, to her husband King Shahryar, who plans to have her executed but continues to stay his orders so he can hear the endings of her 1,000 tales. After nearly three years of excellent stories, he lets her live as his queen.

A few of these stories — The Seven Viziers, The Three Apples, and The Hunchback’s Tale — include early versions of the unreliable narrator trope. The first story contains several short tales exploring the idea of unreliable narration and the idea that a storyteller could be misinformed. It provides the quote at the beginning of this section. The second is an early detective story where the characters do not have all the information. The last is a courtroom comedy in which a dozen people on trial for murder try to explain how an unfortunate fellow met his end.

These stories are some of our earliest examples of explicitly unreliable narration. This doesn’t mean that the stories are unenjoyable, though. Rather, these fun stories provide a look at how a curious tool in the writer’s kit has aged. Given the age of the text, free-to-read versions exist.

Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn

“When I think of my wife, I always think of her head. I picture cracking her lovely skull, unspooling her brains, trying to get answers. The primal questions of any marriage: ‘What are you thinking?’, ‘How are you feeling?’, ‘What have we done to each other?’.”

Gone Girl is a 2012 crime thriller and psychological drama exploring the disappearance of a housewife from the perspective of the missing woman and her husband. The novel explores the different ways that two people can see a marriage and how external viewers, such as the media, can decide that a given narrator is lying. Full of twists and turns, the story repeatedly leaves the reader wondering what exactly happened. It was made into a film in 2014.

The story begins by reflecting on the marriage of Amy and Nick Dunne, of North Carthage, Missouri. Nick’s section begins shortly after finding his wife missing. Amy’s comes from a series of diary entries from an earlier part of their lives together. However, not all is as it seems.

Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

“The following decision I make with all the legal impact and support of a signed testament: I wish this memoir to be published only when Lolita is no longer alive.”

Lolita is a novel by Russian-American author Vladimir Nabokov. The story is told from the perspective of Humbert Humbert, a self-pitying abuser who recounts the events of his life. The story is most famous, and infamous, for its depiction of Humbert’s sexual fixation on his landlady’s daughter Deloris, whom he calls Lolita.

Humbert Humbert, which is the character’s nom de plume, describes his life as he awaits his trial. In many cases, it is clear that he is not giving the reader the full story and is actively trying to make himself come off as less of a monster than he is, or even as sympathetic to a jury. Several scenes in the novel approach surrealism. In others, Humbert admits how wonderfully convenient certain plot points are. The frequent references to other works — Humbert’s first love is named similarly to Poe’s Annabelle Lee — also imply that his descriptions are less than factual.

As you might have guessed, a novel focusing on a pedophile has proven extremely controversial over the past 70 years. The fact that he is an unreliable narrator often escapes people, especially those who saw the movie. The choice of telling the story from the point of view of the repulsive Humbert, who tries to depict himself as debonair, doesn’t help. This also provides a powerful metaphor: We never hear the victim’s voice without the filter of her abuser. It might even be said we never see or hear from Deloris herself, but only the version of the girl in Humbert’s mind: Lolita.