From Poe to Mao: piecing together the evolution of detective stories

- Critics concur that the modern detective story was developed by Edgar Allen Poe.

- Where western crime fiction was concerned with solving crimes, Russian books asked why these crimes were being committed in the first place.

- In Maoist China, detective fiction acquired both a revolutionary and counter-revolutionary taste.

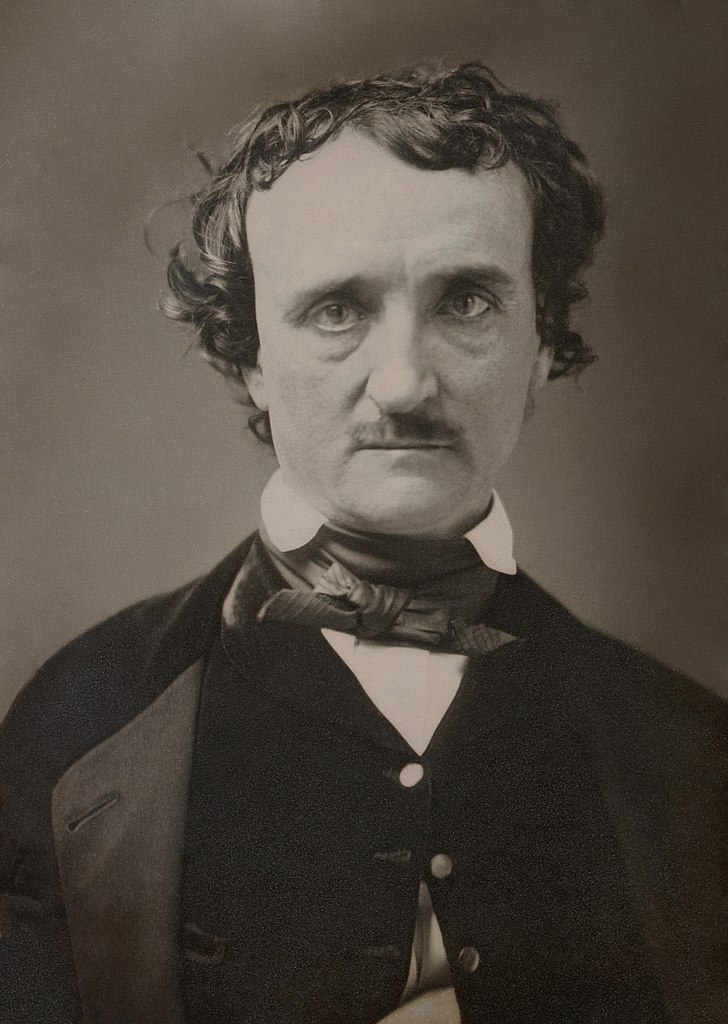

Many literary critics trace the development of the modern detective story back to The Murders in the Rue Morgue, a 1841 short story by the American author Edgar Allen Poe. Poe’s writing often centers around mysterious or macabre subject matter, and The Murders in the Rue Morgue is no exception. Published in a magazine that Poe edited himself, the story begins when two Parisian women are brutally murdered by an unseen subject speaking an unknown language.

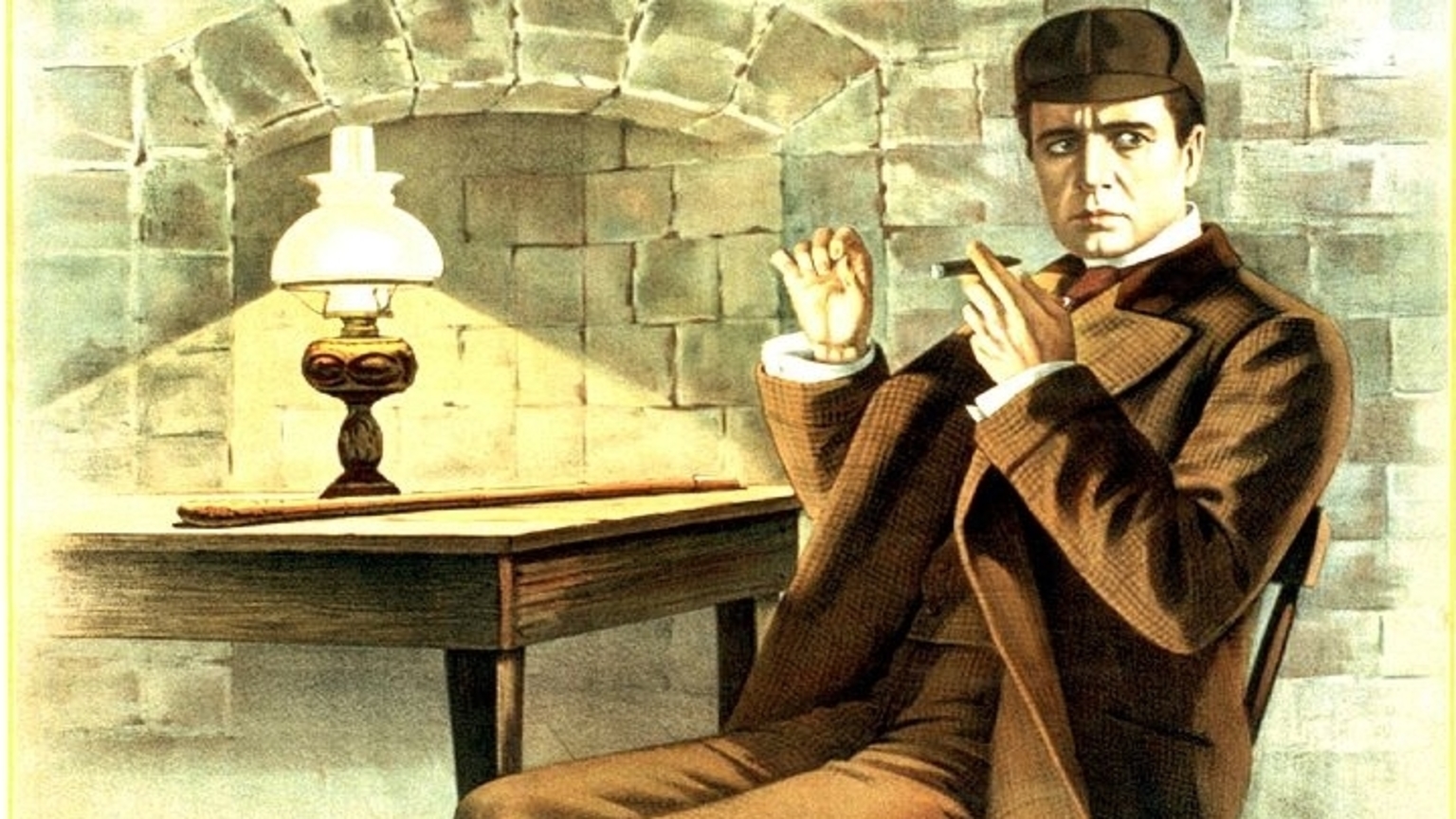

The Murders in the Rue Morgue has shaped the detective genre in more ways than one. The most obvious of these has to do with character. The story’s unlikely protagonist, an armchair detective named Auguste C. Dupin who solves the case by thinking outside the box, was a major inspiration for Arthur Conan Doyle’s own Sherlock Holmes. The story’s narrator, a friend of Dupin’s who never ceases to be amazed at the detective’s deductive reasoning, found a spiritual successor in Doyle’s Dr. Watson.

Poe also provided the detective genre with a conceptual framework. The author famously referred to The Murders in the Rue Morgue as a “tale of rationication.” The critic A.E. Murch explains the meaning of this term when he writes that the primary interest of detective stories “lies in the methodical discovery, by rational means, of the exact circumstances of a mysterious event or series of events.” Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes books are tales of rationication as well, as is Ryūnosuke Akutagawa’s In a Bamboo Grove.

“The true detective story as Poe conceived it is not in the mystery itself,” adds Columbia University drama professor Brander Matthews, “but rather in the successive steps whereby the analytic observer is enabled to solve the problem that might be dismissed as beyond human elucidation.” The identity of the criminal is less important than the process through which this identity is revealed; fittingly, the culprit of The Murders of the Rue Morgue — spoiler alert — is an escaped orangutan.

The whodunit vs the whydunit

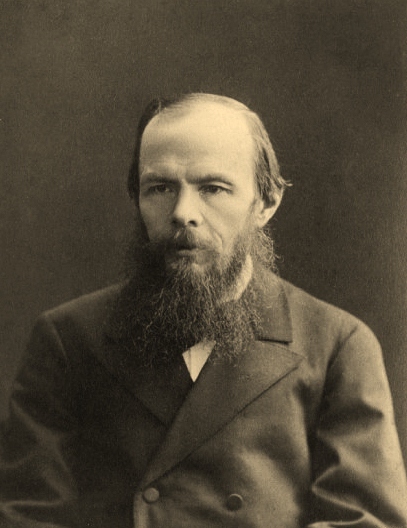

Poe’s focus was on the plot structure of a criminal case, not the emotional consequences or philosophical implications of the crime itself. These equally fascinating aspects of the detective genre were being explored in another part of the world: Russia. Crime fiction was incredibly popular during the late nineteenth century; examples include Nikolai Sokolovsky’s Prison and Life, Nikolai Timofeev’s Notes of an Investigator, and — last but not least — Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment.

Despite its title, Crime and Punishment is rarely characterized as a crime story. When the novel was first published in 1866, it was read within a realist rather than speculative context. However, the religious and socioeconomic undertones of Dostoevsky’s book should not distract from its use of genre tropes. Nor should those tropes — as scholar Claire Whitehead, author of The Poetics of Early Russian Crime Fiction, told the North American Dostoevsky Society — take away from the book’s deeper meaning.

Whitehead points out several similarities between Crime and Punishment and more straightforward crime fiction. Sokolovsky’s Prison and Life follows a judicial investigator working criminal cases, but also features close encounters with incarcerated individuals similar to those we find in Dostoevsky’s oeuvre. Shkliarevsky’s 1872 story Why Did He Kill Them? is about a man who strangles his wife and shoots his mistress, only to find himself in an existential predicament not unlike Raskolnikov’s.

American and European crime fiction tends to follow the familiar “whodunit” format. Russian crime fiction, on the other hand, can be organized under the term “whydunit.” These formats, explains Whitehead, represent two different attitudes toward criminal justice: “whilst the ‘whodunit’ accuses an individual, the ‘whydunit’ points the finger of guilt at broader, more collective social forces.” Unsurprisingly, authors like Dostoevsky were a major influence on Russia’s socialist revolutionaries.

The detective story in Maoist China

Detective stories are a cultural universal because no society is devoid of crime and every human loves a good mystery, among other possible explanations. The aforementioned story In a Bamboo Grove was first published in Japan in 1922. Inspired by Poe, its mystery is set in feudal Japan and relates the violent death of a young samurai through the conflicting testimonies of several witnesses, including his wife and a bandit. The story was famously adapted into a film by Akira Kurosawa.

China’s detective stories are likewise inspired by the Western model. During the early 20th century, Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes books were translated into Cantonese. So great was the demand for this genre that one translator, Cheng Xiaoqing, created a Sherlock of his own. Cheng’s hero, Huo Sang, could interact with Chinese culture in ways his British counterpart never could. He is joined by a narrator-accomplice named Bao Lang, and sometimes pitted against a nemesis known as the South-China Swallow.

The Huo Sang series enjoyed tremendous success during China’s Republican period, but disappeared from print once Mao Zedong rose to power in the 1940s. The reasons for this were both manifold and scarcely explained by government decision-makers, but mainly revolved around communist ideology. Cheng was inspired by Western, capitalist source material. On top of that, crime fiction was believed to have no place in a society which attempted to become (and professed to be) free of criminal activity.

One of Cheng’s successors, Qiu Xiaolong, emigrated to the US to avoid persecution following the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989. Here, he penned a series of books about Chen Cao — a police inspector from Shanghai who previously worked as a poet and translator. Cao’s strong moral compass causes him to walk a fine line between rebellion against and obedience to the society in which he operates, not unlike contemporary American productions such as Mindhunter or even The Batman.