Why are flood myths so common in stories from ancient cultures around the world?

- World mythologies are full of floods, plagues, resurrections, trickery, and patricide.

- There are three main theories for why these structural and symbolic similarities exist.

- Regardless of which theory is true, they shed light on the beliefs we all share today.

As the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss notes in “The Structural Study of Myth,” there is an “astounding similarity between myths collected in widely different regions.” From the city-states of ancient Greece to the hunter-gatherer tribes of the Amazon rainforest, cultures everywhere have preserved suspiciously similar stories about heroes slaying monsters, talking animals playing tricks on each other, and jealous (usually male) siblings fighting to the death.

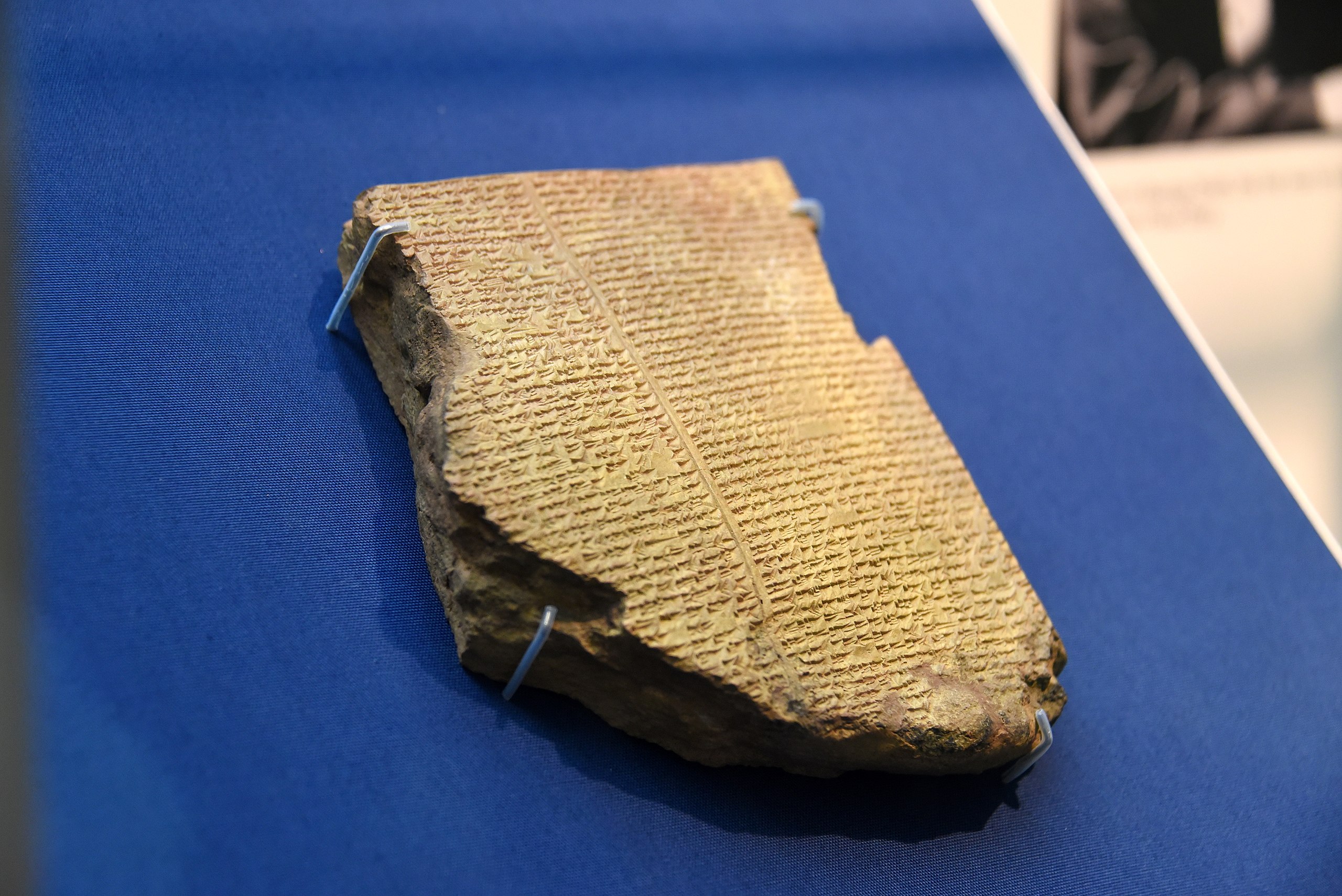

Especially common in world mythologies are stories about world-ending floods and the chosen individuals that managed to survive them, like the biblical Noah and Utnapishtim, the ark builder in the Epic of Gilgamesh, a text thought to be even older than the Abrahamic religions. In Aztec mythology, a man named Tata and his wife Nena carve out a cypress tree after being warned of a coming deluge by the god Tezcatlipoca, while Manu, the first man in Hindu folklore, was visited by a fish that guided his boat to the peak of a mountain. The list goes on.

This all begs the question: Why is there such astounding similarity between the oral traditions of geographically separated peoples? Anthropologists, psychologists, and archaeologists have spent years looking for an answer. To this day, however, there still isn’t a theory that everyone agrees with.

Some argue that these similarities are evidence of cultural transmission in the distant past before human migration really got underway. Others maintain that they developed independently as the result of comparable experiences. Others still believe that it has something to do with the way our brains work. Which of these, if any, is correct?

The world’s oldest flood myth

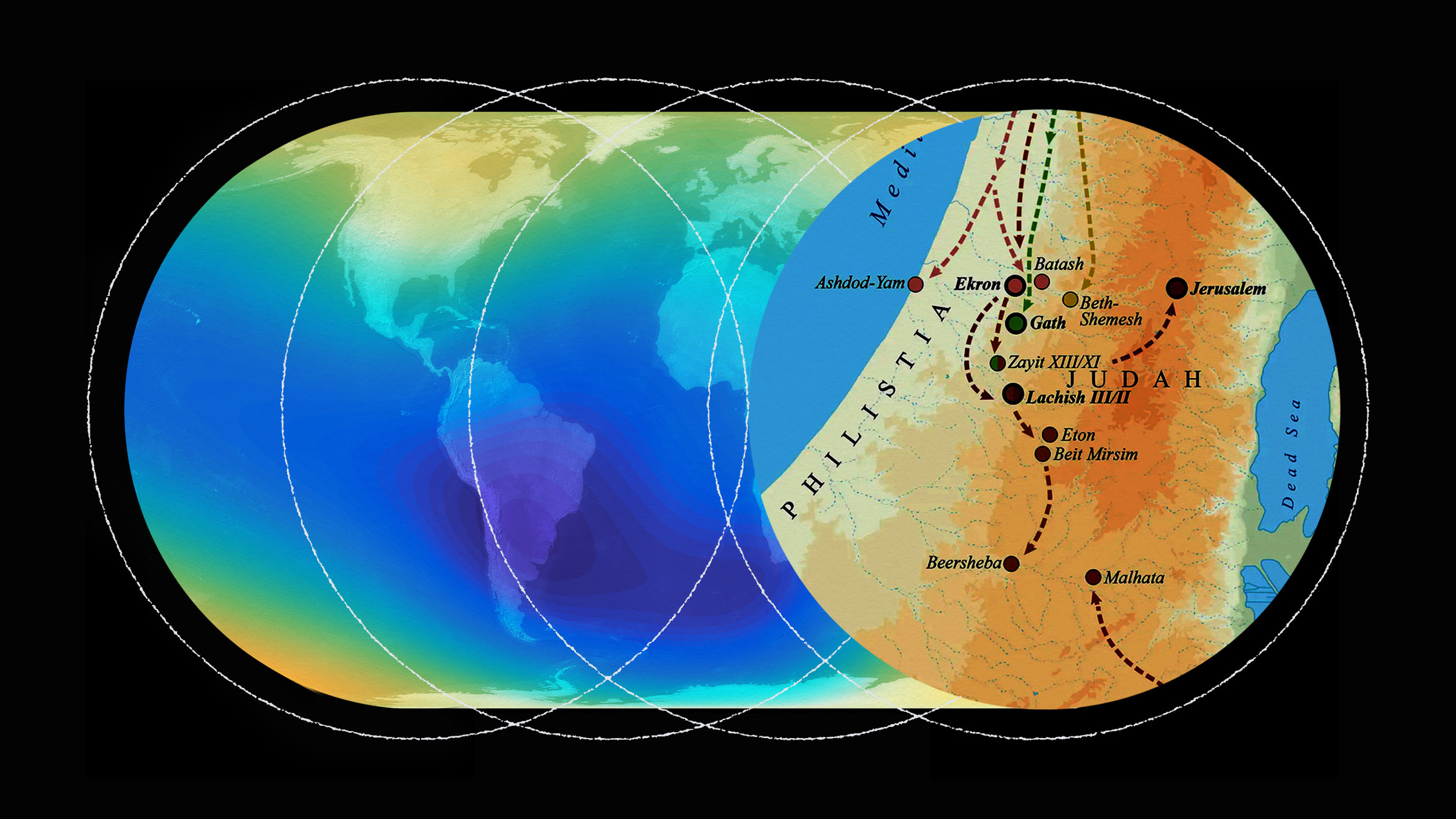

Archaeological research suggests that our species originated in Sub-Saharan Africa, then spread to the rest of the world via the Middle East. This means cultures that are geographically separated at present would have been able to exchange beliefs and practices back when they lived in roughly the same area. Therefore, patterns in world mythology could help us better understand patterns in early human migration and vice versa.

There is no shortage of research on this topic. Anna Rooth, author of “The Creation Myths of the North American Indians,” analyzed small narrative details in more than 300 Native American creation myths and found that many of those details also showed up in myths from Eurasia. This led her to the conclusion that, “because of the special combination of detail-motifs, these myths must be considered to have a common origin.”

In “Oedipus-type Tales in Oceania,” William Lessa writes that legends resembling the famous Greek tragedy are distributed across a “continuous belt extending from Europe to the Near and Middle East and southeastern Asia, and from there into the islands of the Pacific,” but are entirely absent from central and northeastern Asia, Africa, Australia, and the Americas, suggesting a lack of cultural transmission between these regions.

It has been argued that flood myths have a common origin as well. The oldest myth we know of comes from Babylon and is mentioned by Eusebius Caesarea, a historian of early Christianity who mentions the lost works of the Babylonian historian Berosus, who in turn talked about lost Babylonian records that allegedly dated back to the empire’s founding at the dawn of civilization itself.

According to Berosus, a great flood took place during the reign of Xísouthros, a Sumerian king who supposedly lived sometime around 2900 BC. Warned of the deluge by a god, Xísouthros built a ship for his family, friends, and various animals — motifs that should sound familiar. Considering he also used birds to locate land after the rain had ended, it’s not unlikely that this legend was the basis for Gilgamesh and Noah.

Yu the Great

But the Babylonian template does not apply to every flood myth around the world, and as the anthropologist Clyde Kluckhohn writes in his article, “Recurrent Themes in Myths and Mythmaking,” ethnographers have been “careful to discriminate explicitly between those that may have this derivation from the oldest and most influential flood myths from the Near East and others that seem definitely ‘aboriginal.’”

Because the aforementioned flood myths of India and Mesoamerica resemble their Mesopotamian counterparts only insofar as they involve gods, boats, and heavy rainfall, it’s been argued that they developed independently of one another. Any similarity between them, the argument goes, is due to the fact that they are based on comparable but nonetheless separate historical events. In other words, while the story of Xísouthros was inspired by a flood that took place in Mesopotamia, the Aztec and Hindu versions were probably inspired by floods that took place elsewhere.

This hypothesis has been picking up steam in recent years as modern research has improved our understanding of the ancient world and its geology. As recently as 2016, for example, a study in Science presented evidence that a landslide in China’s Jishi Gorge would have sent over half a million cubic meters of water down the Yellow River per second, placing much of the country under water.

What’s notable about this study is that it proposes that this particular catastrophe — which the researchers estimate happened around 1920 BC — served as the inspiration for several Chinese flood myths that emerged during the same time period.

This would explain why one myth involving the legendary founder of the Xia dynasty, Yu the Great, is fundamentally different from other flood myths. Whereas Noah, Utnapishtim, and Tata — to name just a few — build their vessels to avoid drowning, Yu relies on his ingenuity to stop the flood itself, draining the lowlands and turning chaos back into order all by himself, without the help of a god.

Myth and mind

A more questionable theory holds that myths resemble one another not because they originated in the same place or were inspired by similar events, but because — on a subconscious level — every human brain makes sense of the world in the exact same way.

This theory was popularized by depth psychologist Carl Jung, who took issue with the still largely unchallenged notion that myths are metaphors used to explain physical processes. Jung felt that using gods and spirits to represent rising tides and growing crops would have been too big of a leap in logic for primitive humans. “Humans,” Robert Segal writes of Jung’s ideas in his book Theorizing about Myth, “must already have the idea of god within their minds and can only be projecting that idea onto vegetation and the other natural phenomena they observe.”

“Anything psychic,” Jung himself further clarifies in Psychology of the Unconscious, “brings its own internal condition with it, so that one might assert with equal right that the myth is purely psychological and uses meteorological or astronomical events merely as a means of expression. The whimsicality and absurdity of many primitive myths often makes the latter explanation seem far more appropriate than any other.”

Regardless of which theory is true — perhaps there is some truth in all of them — distinctions between the myths are not trivial. Instead, they are what allow anthropologists to discern how one ancient culture might have differed from another in terms of their belief systems, social structures, and family dynamics. Ultimately, they shed light on the beliefs we all share today.