Meet the 3rd bestselling poet in world history

In September 1923, Alfred A. Knopf brought out a slim, hundred-odd page volume. The publisher did little to promote it, yet its first print run (some twelve hundred copies) sold out within a month—unheard-of for a poetry volume, then and now.

Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet was a slow but steadily growing burn, one that has continued, year on year, for ten decades.

Interspersing twenty-six short prose-poetic pieces with original illustrations, The Prophet has made Gibran the third-bestselling poet in history—behind Shakespeare and Lao Tzu. To date, The Prophet has sold more than 100 million copies worldwide (over 10 million in the United States alone) and has been translated into more than a hundred languages.

Yet The Prophet has always been and remains uniquely troublesome, and to call it the bestselling “poetry book” of its century might be misleading. Is it poetry? Or is it (in today’s language) Inspirational Fiction, wisdom text, a spiritual guide of New Age wellbeing or self-help? Perhaps (to deploy a paradox, Gibran’s favorite device) it is all these things and none of them.

Gibran wrote once of his desire “to write a book that heals the world.” The Prophet was that dream’s fruition. Yet his other work—eight English language collections and more books, poems, and other writings in his native Arabic—is largely ignored in the Anglosphere. The Prophet is thus a bestseller with an almost anonymous author. Gibran’s book has outlived him in more than one sense. Though it has had the kind of afterlife of which he himself can only have dreamed, there is in this a strange irony. Gibran was so successful in his likely aim—absorbed into the figure of “The Prophet,” imitating the unknown authors of scripture—that, for many readers and lovers of his book, he remains irrelevant.

It is a very different story in Arabic, where Gibran is held to be a crucial modern innovator, a transitional bridge between the conventions and strictures of a more classical tradition and a newer, freer, romantic sensibility. In Gibran’s case, the adage of the prophet without honor in his home country is inverted. In the West (where Gibran made his home and sought recognition) academic and “literary” opinion regards his concerns and their treatment as utterly anti-modern. He is, indeed, heretically retrograde: fancily faux-Biblical, extravagantly overwritten, vague, naïve, sentimental, and whole lot of other things, terms often directed in baffled rage at Gibran’s apparently undeserved popular appeal. The year 1923, after all, saw the debuts of Wallace Stevens and other modernist high priests in the United States and came hot on the heels of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land and James Joyce’s Ulysses the year before. In his adopted tongue, at least, Gibran was an artist out of time.

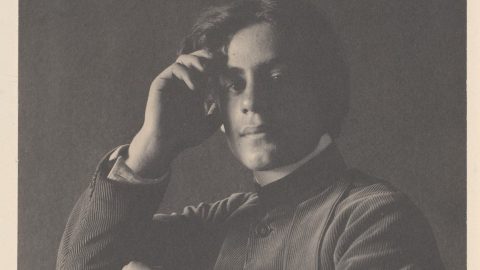

He was born Gibrān Khalīl Gibrān bin Mikhā’īl bin Sa’ad, in 1883, in the mountain town of Bsharri in modern day Lebanon, then part of the Ottoman Empire. Raised a Maronite Christian by tolerant parents in a country riven by religious and ethnic factionalism, Gibran’s mind was exposed early to a diversity of worldviews, and he wove them into his work. When he was twelve, he emigrated to Boston with his mother and siblings, leaving behind his father, who had become an increasingly violent drunkard. They lived in the immigrant districts of Boston’s South End, where Gibran went to public school with Chinese and other immigrant children.

Gibran was a dreamy, beautiful, and artistically talented boy, both in writing and drawing, and he came to the notice of other artists and social workers in the city. It was through admirers, for whom he was something of an “exotic,” that Gibran got his first exposure to Western and avant-garde arts: Wagner, Whitman, Nietzsche. He returned to Lebanon at fifteen for four years of schooling, then made his way back to Boston in 1902. In 1911, he moved into a small studio in New York where he stayed for the rest of his life, writing and drawing––and, increasingly, drinking––for long, late hours in what came to be known as his “hermitage.” Before that, in 1908, Gibran trained at the Académie Julian in Paris, and ultimately produced over 700 visual works in his lifetime, seeing himself in the same poet-artist lineage as his hero, William Blake––whose writings he called “so far the profoundest things done in English…the most godly.”

Gibran had published two English works—and more Arabic ones—before The Prophet, both also published by Knopf. They shared the same form of prose poems written in aphoristic, oracular style. Knopf himself did not particularly seek to market The Prophet, expressing bafflement at its success: “I haven’t met five people who ever read Gibran.” Each year, though, more copies sold. By 1938, with an American populace in need of spiritual guidance in the face of economic depression and political instability, the book sold over 100,000 copies. During the war, it was distributed to soldiers in a pocket-sized Armed Services Edition. By 1957, the book had sold a million American copies. The 60s were its apogee—at its height, 5000 copies were selling a week—and it became, in effect, a counterculture alternative to the Bible.

A sampling is enough to give a sense of Gibran’s register of language and address, as well as The Prophet’s (virtually non-existent) narrative. It opens:

Al-mustafa, the chosen and the beloved, who was a dawn onto his own day, had waited twelve years in the city of Orphalese for his ship that was to return and bear him back to the isle of his birth.

Before the prophet’s departure, however, the townspeople gather to see him off. “A seeress” named Almitra requests:

Yet this we ask ere you leave us, that you speak to us and give us of your truth. And we will give it unto our children, and they unto their children, and it shall not perish.

And so, Al-mustafa obliges, each chapter being a sermon based on different questions about the basic and essential matters of human life: love, marriage, children, food, work, houses, business, law and order, beauty, education, faith, death. The tone of these lines—the grandiloquent epithets, some archaic diction, rarefied Biblical cadences replete with Biblical ‘Ands’ and Whitmanian deployment of repetition, both terse and ripe, and humorlessly sincere—give a good flavor of the whole. Alongside the Christian influence of his upbringing and the language of the King James Bible, Gibran drew on the Islamic tradition and Sufism that he had also observed in Lebanon, alongside Buddhism, Hinduism, Blake, Nietzsche, Whitman, and the Transcendentalist, Romantic and Symbolist writers.

What, then, of this prophet’s philosophy? It will certainly read differently for different people, but there are a few clear threads that read as very modern indeed, for good reason. Gibran played a hardly insignificant role in shepherding us toward the contemporary miasma of “spirituality without religion.” What he managed, for many readers, was to write the sacred text for modern values, which is sometimes a suspicion of all values in and of themselves.

In Al-mustafa’s teaching, the real and essential “truths” as to how we should live our lives cannot, in fact be taught. This is the essential, and characteristically paradoxical, teaching of The Prophet. The prophet we seek tells us that we do not need him.

“The teacher,” Gibran writes, “does not bid you enter the house of his wisdom, but rather leads you to the threshold of your own mind.” It seems a strange message for a book of apparent wisdom, and yet it is one entirely fitted for the twentieth century reader (justifiably) full of doubts about the nature of authority—and not merely of the religious sort. From his teachings on the nature of children (“Your children are not your children…And though they are with you yet they belong not to you”) to the nature of love (“All these things shall love do unto you that you may know the secrets of your heart, and in that knowledge become a fragment of Life’s heart”) the same refrain recurs: that truth comes only from within.

If all this sounds woo-woo, vague and mystical, it’s because it probably is—but only in the same way that Gibran’s inspirations were too. The message—that everything also contains the elements of its opposite, and that oneself is both irreducibly alone and inconceivably part of a larger whole, that we do not learn, but mysteriously “discover” our inner selves—may be obvious or meaningless depending on one’s sensibility. It is also, for many, a profoundly, mysteriously, bafflingly true fact about the experience of living. Such simple and bottomless truths are so hard to express that they can seem obvious—and so become clichés upon utterance. Gibran’s book is one such attempt to express and revivify these truths. Whether he succeeds or not is subjective, but (to follow the number one rule of criticism) he ought not be criticized for not writing the sort of work he was not attempting to write.

Perhaps a way to see The Prophet afresh today is instead to reverse the trend of killing Gibran the author from his work, and to bring him properly to the picture. Many accuse him of pandering to an America that was spiritually exhausted, curious, hungry for rejuvenation with “Oriental” spiritualities, but still wanted flattering and to be spoken of in ways it could understand. As the Arabic literature scholar Nadeem Naimy, nephew of Gibran’s friend Mikhail Naimy, writes: “To be an emigrant is to be an alien. But to be an emigrant mystical poet is to be thrice alienated.” If his book is read as the work of a Lebanese Christian from a majority Muslim nation, struggling to free itself from a crumbling empire, living in an adopted country where he would forever be seen in one or another form as other, we can begin to place it in more solid ground.

The othering of the young Kahlil by enthusiastic artistic circles in Boston, and later New York, in which he was treated by many as “the prophet” avant la lettre, must have left some complex imprints on him. On the one hand, he clearly internalized the philosopher-poet-priest image such patrons projected onto him. It became an inseparable part of his identity, his sense of artistic calling. On the other, this strangely self-observant, self-consciously “Eastern mystic” image is likely to have further complicated his relationship to his Arabic and Lebanese heritage. “I’m a false alarm,” he told a friend—disavowing, for once, his own grandiosity. His end, precipitated by alcoholism, speaks to this inner malaise. He died at 48 in 1931, of cirrhosis among other complaints.

Yet the tortured attempt to speak across culture, resolving a crisis of identity in universal terms is still meaningful. It will only become more so as migration and intercultural confusions become the inescapable human trends of a warming century. Two contemporary readers of Gibran, the actress Salma Hayek, who produced an animated feature of The Prophet in 2015, and the doyenne of Instapoets Rupi Kaur, who wrote a foreword for The Prophet’s 2019 Penguin edition, both likened encountering the work to a wisdom-filled conversation with their grandfathers—from Lebanon in Hayek’s case, and in Kaur’s, India.

Indeed, the success of popular poets, like Kaur, on Instagram and elsewhere in what Global modern literature and media scholar Aarthi Vadde dubs “the digital literary sphere” is equivalent to the word of mouth success of The Prophet, independent of the literary establishment. This is not to mention the many successful novelistic careers launched via web publishing and self-publishing ventures—including, now, Tik Tok. As Vadde points out: “If the novelists strive to entertain, the poets aim to inspire. Each group builds massive followings that operate entirely outside the professional literary circles that dictate prestige.” Kaur’s work is shared and spread, by millions, freely. It proves that there is more than one way for poetry to mean. In his early, democratic virality, Gibran certainly proved prophetic.

Gibran’s poetry lives publicly in a way poetry largely ceased to do in the West throughout the twentieth century. His verses on love and marriage have been vows at weddings for the “spiritual but not religious;” read as solace by the incarcerated; recited at Mandela’s funeral. It must also be one of the most oft-given books in the world, presented both in times of celebration and sorrow.

There is no doubt that Gibran is a godfather of the “New Age,” and that it was his sincere—if grandiose—wish “to write a book that heals the world.” What is often sought in “inspirational” texts, whether the Gospel of John or The Secret, is not “inspiration” so much as authority—something that will bolster or expose what was already within us by the affirming voice of an “other.” As a text, this is what The Prophet is essentially about. As the poet himself put it, “No man can reveal to you aught but that which already lies half asleep in the dawning of your knowledge.”

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story failed to indicate that Lebanon, a majority Muslim country, has long also been home to other large religious communities. It also erroneously suggested that The Prophet was the only poetry collection released in a pocket-sized Armed Services Edition.

This article appeared on JSTOR Daily, where news meets its scholarly match.