How Michelangelo’s David turned Renaissance Italy on its head

- Michelangelo’s David was initially supposed to be set atop the Florence Cathedral but was instead placed in the Palazzo Vecchio.

- Some historians suspect the placement of the statue — a well-known anti-Medicean symbol — may have been politically motivated.

- Transcripts of the committee that oversaw its installation reveal a rift that had been growing between Florentine republicans and Medicean sympathizers.

On January 25, 1504, a small committee of influential Florentines came together to decide on a location for a massive, brand-new statue of the Biblical hero David. Its creator, Michelangelo, had begun working on the 17-foot-tall sculpture under the impression that it would be placed on the rooftop of the Florence Cathedral. When builders proved unable to get the 12-ton block of solid marble off the ground, the committee assigned it a new home inside the city’s town hall, the Palazzo Vecchio.

Moving David proved cumbersome for numerous reasons, including the fact that the statue was extremely heavy. Forty strong, young men had to be recruited to haul the figure from Michelangelo’s workshop to the entrance of the Palazzo. Although it was only a half-mile away, the journey took four days. Once at its destination, David went on to replace another large Biblical statue, one made of bronze and sculpted by Donatello.

Even more problematic than transporting the statue were the fierce discussions that preceded its physical relocation. Transcripts from the committee’s meeting, collected in a volume from the archives of the Duomo, show that up to nine different locations for the statue were initially considered. Of these, the Palazzo and the Loggia dei Lanzi pitted the participants against one another. After everyone had a chance to speak their mind, votes were cast, and the Palazzo was selected.

Up until recently, these transcripts received little to no attention from Renaissance historians. They were read only to trace the statue’s provenance, and never analyzed for any deeper, hidden meaning. This, according to Saul Levine, was a grave mistake. Tackling the text with a thorough understanding of the time in which it was written, the critic unearthed a previously overlooked conflict fought between the city’s rulers — one in which Michelangelo’s David played a small but incredibly important role.

David as the personification of Florence

When the administrators of the Palazzo unveiled David to the public, the statue was considered somewhat controversial. Not so much in style — Michelangelo had not only adhered to but improved upon the traditions of Renaissance sculptors — but in presentation. With the town hall behind him, the hero looked as though he were preparing for battle. His gaze, deliberate or not, was fixed in direction of Rome, the place to which Florence’s recently deposed rulers — the Medicis — had fled.

To unpack the full story that was being told by this provocative setup, we must first explore the symbolism behind each individual image, starting with David. According to University of Virginia history professor Paul Barolsky, there was a longstanding tradition in Italy of revering the Biblical figure as the patria, a father to and protector of both society and culture. Aiming to depict him as a guardian, Michelangelo rendered David taller, more handsome, and more muscular than Bible passages suggested.

A similar vision of David can be found in the work of another famous Florentine, Niccolò Machiavelli’s book The Prince. Describing how David “rejected” the weapons Saul offered him and chose to fight with his own sling and knife instead, Machiavelli turns the character into a metaphor for the city-state, and his story an allegory for how to defend it. “In conclusion,” he said, “the arms of the others either fall from your back, or weigh you down, or they bind you fast.”

Given that Machiavelli was still writing The Prince when Michelangelo had completed David, the philosopher’s introduction to the statue must have resonated with him on a personal level. Barolsky wrote that he can easily picture Machiavelli standing in the piazza and looking up at the hulking statue: “Machiavelli, I would suggest, exploited the powerful, gigantic image of Michelangelo’s David, who personified the city’s capacity to defend itself with its own arms.”

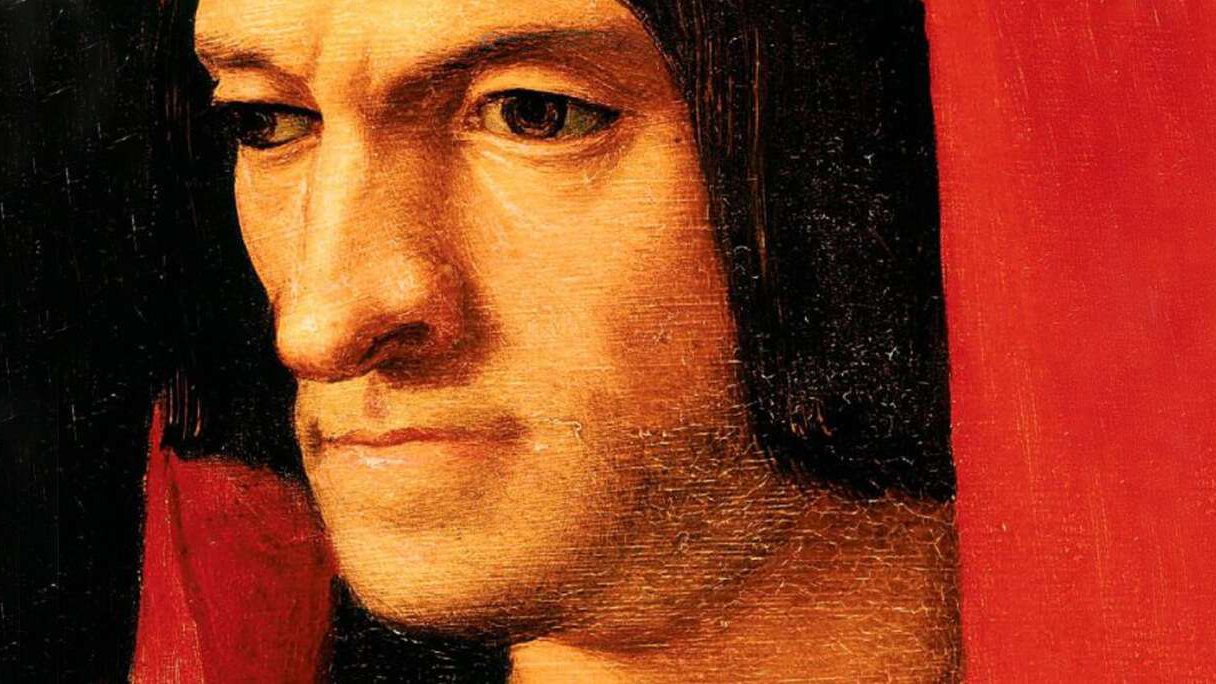

Goliath as the overthrown Medici family

If David represented Florence, who was Goliath? Michelangelo’s decision to exclude David’s main adversary from the scene was as surprising as it was suspicious. Few if any Renaissance painters had done this before, probably because it did not make a lot of sense. Without Goliath, onlookers would have no frame of reference with which to perceive David’s most important trait: his short stature. Consequently, their clash would be robbed of its gravitas.

In his article, Levine suggests Michelangelo’s Goliath was missing in action because the people whom the evil giant was meant to represent were absent from Florence as well. Just a couple of years prior, the Medicis — whose family had ruled the city for generations — were ousted during an uprising led by a friar named Girolamo Savonarola. Determined to reclaim their seat of power, they fled to Rome, trailed by the stone-cold gaze of David.

Fear for the Medici family’s wrath was so widespread among republicans during this time that Levine feels confident in proclaiming they are the faction that Michelangelo’s unseen Goliath is meant to symbolize. Having established some context for the transcript, his close reading hints at a rift between republicans looking to assert their dominance of Florence and Medicean sympathizers wanting to prevent their former lords from falling victim to propaganda without risking their own careers.

Unwilling to display an anti-Medicean icon in front of the Palazzo, the sympathizers — led by architect Giuliano de Sangallo — urged the committee to place David inside the Loggia, indoors and hidden from public view. Rather than stating their treasonous motivations outright, Levine thinks the sympathizers hid behind a politically neutral excuse: an unfounded fear that continuous exposure to the elements would cause Michelangelo’s masterpiece to deteriorate faster than if it were moved indoors.

A clash between republicans

The republicans, seeing David as a symbol of their government and its ability to withstand foreign threats, wanted the statue to be placed near the Palazzo: the building that housed their nascent government. Speaking to the rest of the committee, Francesco Guicciardini — recorded in the transcripts as the “Herald of the Signoria,” Florence’s current ruler — said the statue would be of “great comfort to the distinguished one” if placed outside his window.

In the same opening remarks, Guicciardini suggested David should replace Donatello’s statue of Judith and Holofernes, a “deadly sign” that had also been a prominent symbol of Medici rule. The Herald made more allusions to the Medici days, adding that the Donatello piece “was placed in its position under an evil constellation” and that, since then, “things have gone from bad to worse.” Case in point: control over Pisa had been lost to other city-states.

“It was because the David was so pointedly an anti-Medicean symbol that the meeting was called,” Levine concluded, “and conversely, the very need for the meeting reaffirms the politically controversial nature of the work.” While other scholars have argued the transcripts are too ambiguous to yield such definitive statements, Levine’s article raises important questions about the timing and placement of Michelangelo’s David, which may well have been a lot more meaningful than previously thought.