Kurt Vonnegut on the 8 “shapes” of stories

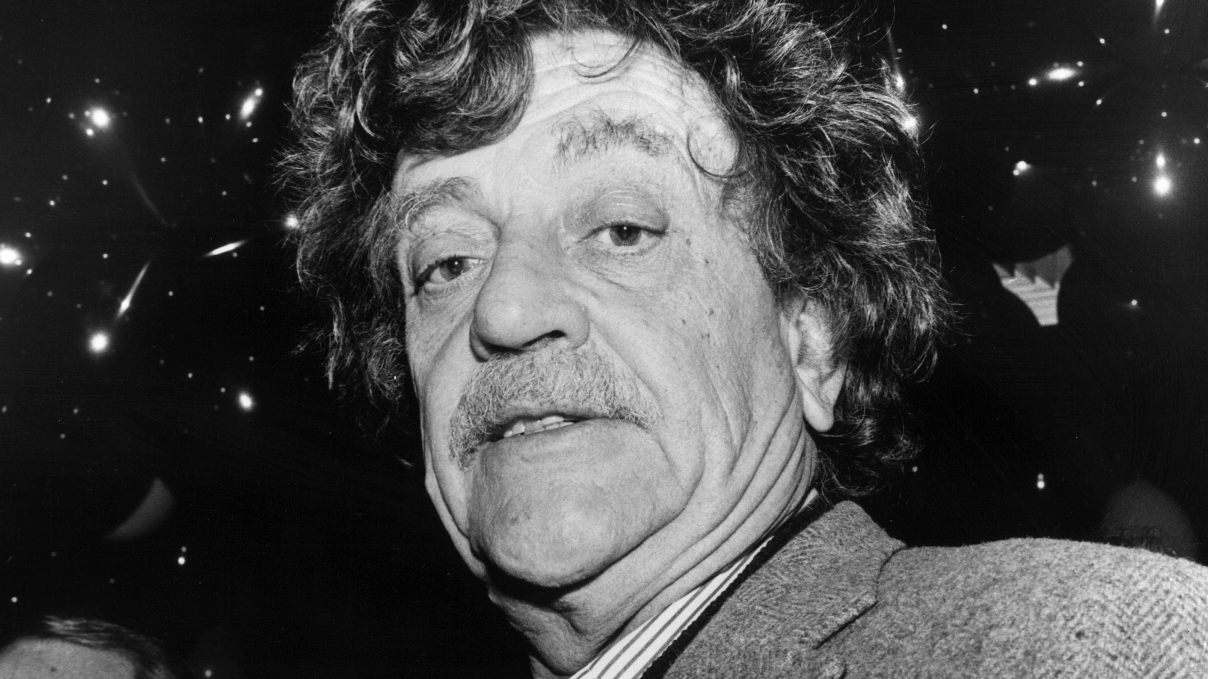

- Kurt Vonnegut wrote a master’s thesis on the shapes of stories that he submitted to the anthropology department at the University of Chicago, which rejected it.

- The late Indiana-born author said it was his “prettiest contribution” to the culture.

- Vonnegut half-jokingly defended his “scientific” approach to literary criticism over his career, but noted that great stories can’t be easily plotted on a diagram.

Stories have very simple shapes, ones that computers can understand.

This was the basic idea behind the master’s thesis that Kurt Vonnegut submitted to the anthropology department at the University of Chicago. It was rejected, however, “because it was so simple and looked like too much fun,” Vonnegut said.

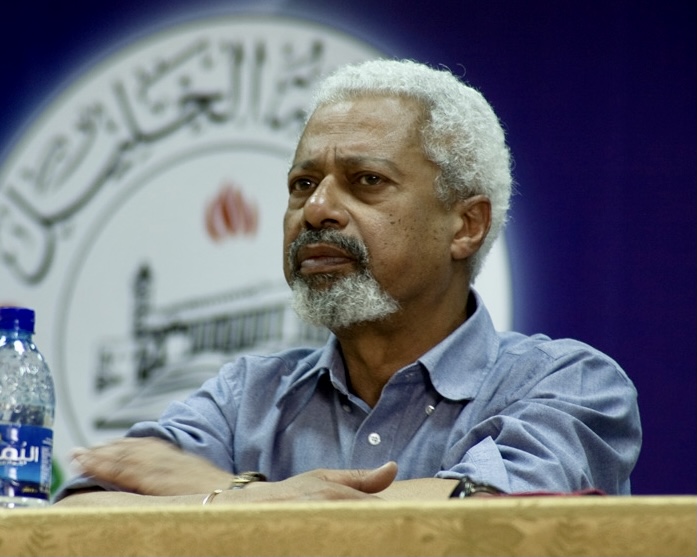

The late American author is best known today for using his dark, dry and decidedly Midwestern sense of humor to satirize American culture and politics in novels like “Slaughterhouse-Five”, “Cat’s Cradle”, and “Sirens of Titan.” But in his autobiography, Palm Sunday, Vonnegut claimed that his “prettiest contribution” to the culture is his theory on the shapes of stories.

“I have tried to bring scientific thinking to literary criticism, and there has been very little gratitude for this,” Vonnegut joked during a lecture at Case Western Reserve University in 2004.

The system involves two axes: the Y-axis represents good and bad fortune, the X-axis represents the beginning and end of a story. Vonnegut explains his system in the video below.

From “boy meets girl” to “man turns into a cockroach”, Vonnegut plots out a handful of story shapes on his diagram and explains why some of these patterns keep showing up in storytelling. To get a better visual sense of the story shapes, check out this great infographic created by graphic designer Maya Eilam.

So, does Vonnegut’s theory actually have useful application in literary criticism?

“I think perhaps it does,” Vonnegut said. “I think this rise and fall is, in fact, artificial. It pretends that we know more about life than we really do. And what’s perhaps a true masterpiece cannot be crucified on a cross of this design. Well, alright. Let’s try ‘Hamlet.'”

Vonnegut describes how Hamlet’s experiences throughout the play can’t easily be classified as good or bad. For example, Hamlet speaks with a ghost who claims to be his father. But Hamlet (and, by extension, the audience) never definitely learns whether this ghost really his father or a demon who’s impersonating him. Ambiguities like this make the story of “Hamlet” difficult to plot on Vonnegut’s diagram. But they also make the story great.

“I have in fact told you why this is respected as a masterpiece. We are so seldom told the truth. In Hamlet, Shakespeare tells us we don’t know enough about life to know what the good news is and what the bad news is, and we respond to that. Thank you, Bill.”

If this isn’t nice…

Real life is too complex to plot on a diagram in any meaningful way. But Vonnegut suggested that learning to see life’s ebbs and flows in stories might help you appreciate when things are good in your life. He concluded his lecture with a bit of advice he picked up from his uncle.

“What uncle Alex found objectionable about so many human beings is that they so seldom noticed it when they were happy,” Vonnegut said.

His uncle made a habit of noticing the good times: When Vonnegut and his family would be drinking lemonade under a tree on a summer day, his uncle would suddenly exclaim, “Wait a minute, stop! If this isn’t nice, I don’t know what is!”

“It was very good advice,” Vonnegut said. “And I’ve taken it up, and I hope that you will take up this habit, too — of noticing when things are really awfully nice, and saying: ‘If this isn’t nice, I don’t know what is.'”

This story was originally published on Big Think in December 2019. It was updated in June 2022.