The extraordinary journey of Leonardo da Vinci’s most mysterious portrait

- In or around 1490, Leonardo da Vinci painted a portrait of a young Italian woman named Cecilia Gallerani, the mistress of Ludovico Sforza, duke of Milan.

- In her 2022 book, What the Ermine Saw: The Extraordinary Journey of Leonardo da Vinci’s Most Mysterious Portrait, Eden Collinsworth covers the origin of the portrait and the many hands it passed through over the centuries.

- The painting depicts Gallerani with a hint of a sly grin, her hair covered by a fine veil as she holds as an ermine whose features and countenance are curiously similar to her own.

Some 530 years ago, a young Italian woman—not much older than a girl, really—sat for her portrait.

It was a customary practice in Europe to commission a noblewoman’s portrait in anticipation of marriage— marriage being a transactional event with political or monetary value. The setting was a sprawling, opulent, Milanese castello, but the young woman’s simply styled dress revealed that she was neither noble nor soon to be married. Instead of being depicted as something akin to an object, she would be well and truly the portrait’s significant subject.

In a time when her sex was expected to harbor unexpressed opinions, the young woman diverted herself during the long stretches of sitting for her portrait by enlisting a circle of learned men with whom to enjoy intellectual conversation. Often they would do this in Latin—a devilishly complicated language whose alphabet is derived from the Etruscan and Greek alphabets and features a nominative, a vocative, an accusative, a genitive, a dative, and an ablative. Some days, the young woman would recite poetry to the men or orate long passages by memory; on other days, they would debate philosophical issues in respectfully low voices so as not to disturb the concentration of the painter, whose focus was forensically trained on the purpose at hand.

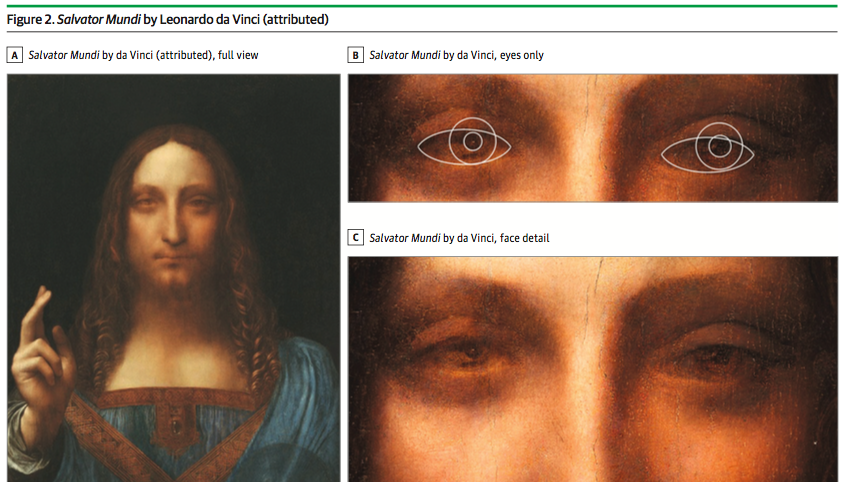

The painter was not just an artist. Indeed, he eluded any number of categorizations, but if there were a central knot of his being, it was curiosity. His fascination with science often informed the methods of how he worked; by studying the anatomy of the human eye, he had gained an understanding of the relationship between light and the size of the pupil, noting that “the pupil of the eye changes to as many different sizes as there are different degrees of brightness” and that in “the evening and when the weather is dull, what softness and delicacy you may perceive in the faces of men and women.” To benefit from this discovery, he would sometimes paint during overcast days or the early evenings when his enlarged pupils would have a sharper focus.

He was in his early thirties and strikingly handsome: tall, lean, with auburn curls flowing past his shoulders and a neatly trimmed beard. He had a perfectly straight, Grecian nose and deep-set, soulful eyes. There was a brio in his style of clothes, which were convention flouting in the best possible way. While most of his male contemporaries wore long garments, he dressed in rakishly short tunics.

As for his character, it was hard to read. He wasn’t thought to be broody as much as self-absorbed. There was a meditative nature about him, and his facial expression often rested in the unsettling border between open and not, making a reading of his thoughts difficult. He appeared most content when left on his own with his notebooks; on the other hand, he could offer himself to conversation with disarming ease and infectious charm. The combination of these two traits enabled him to portray the interior life of the subjects he painted while revealing very little of his own.

The painter’s way of working required time, and his refusal to be rushed with a commissioned work often frustrated his patron, but so admired was he—so unrivaled were his talents—that he was granted as much time as was required. That said, the young woman and her retinue thought it odd that as they passed his easel while filing out of his studio after each of the sittings, they could see that no brushstrokes had been made on the wood panel where there was meant to be an emerging image. Unbeknownst to them, the painter had already conceived the portrait. In order to capture the fluidity of the young woman’s grace before painting her, he had investigated the mechanics of how her head and shoulders would move as she turned. To illustrate his understanding, he drew eighteen rapid compositional sketches of a model’s head in a revolving sequence.

Just as the painter took a systematic approach to his working methods, so too did he pay fastidious attention to its preparations. The wood panel on which he would paint the portrait was small—a mere twenty-one and three-eighths inches high and fifteen and a half inches wide. So that it would remain impenetrable to worms, he instructed his assistant to wash it thoroughly with a solution of brandy mixed with sulfurous arsenic and carbolic acid. To fill the panel’s tiny holes and close any of its thin vein-like cracks, it was covered with a thin paste of alabaster. The panel was sealed by applying a lacquer of cypress resin and mastic. Once the lacquer dried, a flat iron rasp was used to smooth away any remaining asperities. Only then did the assistant prime the wood panel with a layer of white gesso—a binder of sorts, mixed with a combination of chalk from bone and gypsum. This was the immaculate surface on which the painter made a preparatory drawing using charcoal powder. The drawing was meant to accomplish nothing more than outline a contoured likeness of the young woman. The rest—the remarkable—was still to come.

It was not the assistant who had moved the panel onto an easel, but the painter so that he could adjust it at his eye level. Under the easel was a centered table, reached easily from either direction. On the table were palettes and shallow cups of colors mixed with precisely calculated formulas. The formulas included certain minerals and seed oils judiciously selected. Nearby were paintbrushes. Some had a slight dusking of chalk on their tips applied the night before to prevent insect damage. The larger brushes were made of hog’s bristles held together by a band of lead; the delicate ones were formed with squirrel hair and goose quill. A number of both kinds had been made with longer handles whose utilitarian purpose was to provide enough distance between the panel and the painter, enabling him to view the entire image without stepping back from it.

Accepting the commission to paint a portrait of the young woman would have obliged the artist to create a flattering impression of her. In this case, there would be no need to enhance reality. She was flawlessly beautiful. In a concession to one of the contemporary fashion trends at the time, gum arabic—a natural gum of the hardened sap from acacia trees imported from the East—smothered her long, shiny hair, which, wrapped around her face, gave her the appearance of a glistening lure. Running across her high forehead was a narrow long fillet holding in place a transparent veil that framed her delicate features. She was radiant: part child, part woman, with lips softened by a suggestion of innocence and clear eyes that had already learned much of life but were eager to see a great deal more of it.

The painter thought her too young to comprehend the world outside the castello, but he admired her intelligence and something she had that he did not—an extensive knowledge of Latin. There were days when he would grant himself the pleasure of listening to the poetry she recited, but none of her silken words would charm the charcoal outline on the wood panel into becoming the painted portrait for which he had been commissioned. That would require an entirely different language, one understood only by him and only when everything else in the studio fell away but his entire concentration. He was ambidextrous. His habit was to draw with his left hand but to use both hands when he painted.

It matters not at all which of his two hands reached for which brush resting on the table under the easel that held in place the wood panel. What matters is that five centuries ago this simple gesture led to the creation of a portrait that, even now, does something very little else can do. It astonishes.

The painter was Leonardo da Vinci. “Learn how to see,” had been his advice. “Everything connects to everything else.”

It is clear from the young woman’s entrancing gaze that something—or someone—has caught her attention. Still, she shows not the slightest sign of strain in the fleeting moment of turning away from the direction she was going in order to look back at that other person. There is a deep intimacy passing mutely between the young woman and someone we cannot see, and whoever that person is, they are more important than you—or for that matter anyone—will ever be.

Had your eyes told you these things as they studied the portrait, they would not have failed their assignment.

The young woman—with her sublime grace and guiltless beauty—seems to be relaying an unspoken message to just beyond the place we are standing. It is for this unseen person that the beginning of a smile plays across the corners of her mouth and passes over her cheeks to reach her eyes.

And what of us?

We are left with a multitude of unanswered questions about the enthralling young woman far away in time but exerting extraordinary power, and whose portrait is made more cryptic by an odd-looking creature cradled in her arms. The creature, too, is suggestive; its tiny claws grasp at a lush cloak that drapes around her as though holding secrets in its dark folds. With the creature’s half-turned head facing the same direction as the young woman, and its eyes fixed on the same object, their slender bodies appear almost as a single serpentine figure. There is something slightly erotic suggested by the serenity with which the young woman is languidly caressing the creature’s neck.

She is known simply as Lady with an Ermine. The year she was painted is believed to be 1490, though even that date is disputable.