The happiest country in the world is… Finland? Really?

- For four years running, Finland has been named the happiest country in the world.

- Finland’s happiness scores have surprised many, not least of all the Finns.

- The lesson isn’t to copy-paste Finnish customs but to find ways to build perseverance and trust into our lives.

If we asked you to picture the happiest place in the world, what would you imagine? Would you envision a lounger placed before a crystal blue ocean? A bustling downtown filled with shoppes and upscale eateries? A neighborhood where people aren’t afraid to just get up and dance?

You likely didn’t think of Finland — a place where the winters are crushingly cold, the people famously introverted, and the local cuisine leans heavily on rye flour and salty licorice. But for four years running, the World Happiness Report has named it the happiest country in the world.

It isn’t the richest country on the list nor the most visited tourist destination. So, what’s so special about Finland?

Is the secret in the sauna?

While having 2 million saunas in a country of 5.3 million people likely doesn’t hurt life satisfaction, per capita sauna allotment isn’t a metric for the world’s happiest country. Since 2012, the World Happiness Report has used Gallup World Poll data to rank worldwide national happiness. It does this by comparing survey results from more than 160 countries, with an average sample size of about 1,000 per country.

The report’s main life evaluation question is what is known as the Cantril ladder. Respondents are asked to think of a ladder with ten rungs. The best possible life sits at the top of the ladder; the worst doesn’t even have a foot on it. They’re then asked to rate their current lives on that 0-to-10 scale. The researchers compare the results and estimate the extent that certain factors contribute — things like generosity, social support, and life expectancy.

(Sidebar: Other poll questions inquire about the positive and negative emotions respondents have experienced recently. For example, did they laugh a lot yesterday? Feel worried? And so on. The World Happiness Report weighs life evaluation questions more as they provide a “complete and stable” comparison. However, you may find it uplifting to learn that the data show positive emotions to be three times as frequent globally than negative ones.)

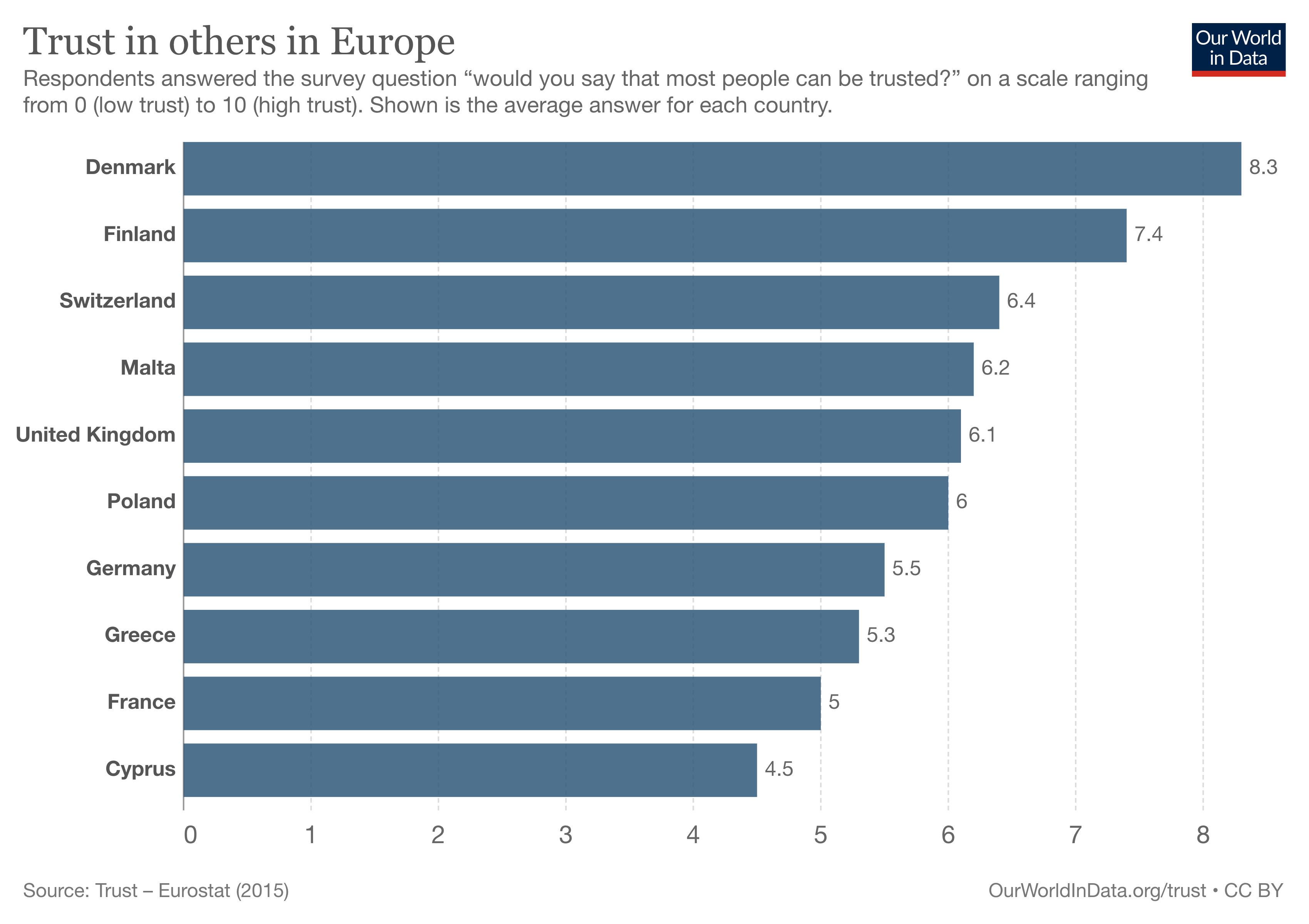

In the most recent report, which looked at the soul-crushing year of 2020, World Happiness researchers also emphasized the link between trust and well-being.

The reason, as the researchers put it, is that: “Trust and cooperative social norms not only facilitate rapid and cooperative responses, which themselves improve the happiness of citizens, but also demonstrate to people the extent to which others are prepared to do benevolent acts for them.

“There is a happiness bonus when people get a chance to see the goodness of others in action and to be of service themselves.”

The “happiest” country in the world

With that methodology in mind we can begin to see how Finland, which at first blush doesn’t seem a contender for the title, can be crowned the happiest country in the world. While it doesn’t elicit the images of escapism people generally associate with happiness — opulent homes, worry-free lives, and sun-warmed, well, anything — the Finns have worked hard to embrace and institutionalize practices that make day-to-day life more satisfying.

“This Finnish happiness we hear about is not about dancing or smiling or being outwardly happy,” Anu Partanen, author of The Nordic Theory of Everything, told the BBC. “If that’s your idea of happy, then no, they are not the happiest. These studies are about the quality of life … Are you living the best one? Can you control your life? Do you have choices? Can you spend time with your family? Do you feel safe? Can you be productive in society?”

Two Finnish concepts serve as potential drivers of this quality of life: sisu and a sense of communal trust.

Sisu is difficult to pin down, especially in English where it has no good equivalent. Determination, perseverance, and willpower have been used as translations, and while they touch on the concept, they don’t encompass it. Its been described by psychologist and sisu coach Emilia Lahti as a “universal capacity” that contributes to an “action mindset” and allows people “to overcome a mentally or physically challenging situation.”

In other words, sisu is that inner strength that helps a writer plug away at a challenging book or a runner push through the wall to finish a marathon. When aggregated to the national level, it’s the on-tap grit that allows the Finns to get it done. Sisu is often credited as the critical cultural trait that allowed the country to outlast the much stronger Soviet army during the Winter War.

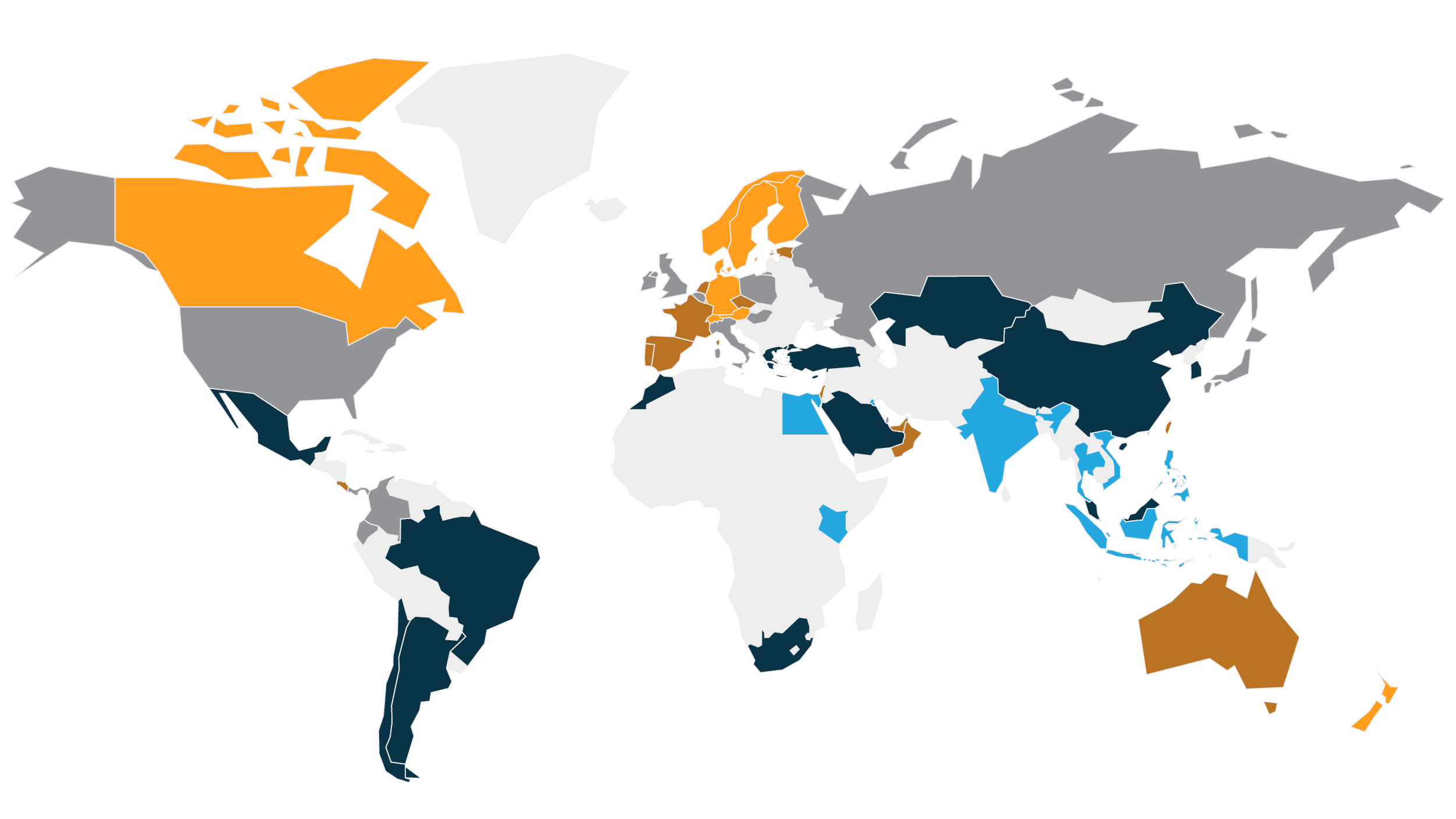

Looking toward their communal mindset, the Finns have worked hard to build trust into their administrative and political models. The results speak volumes. The Finns have some of the highest levels of trust in the world, both in one another and in their government. And as Partanen’s quote suggests, the desire to be a productive member of society is not only strong but has cultivated the country’s powerful social programs. Today, Finland enjoys a low poverty rate, scores high in markers of health, leads the way in gender parity, and has developed a top-ranking education system.

The paradox of happiness: Finland edition

How do sisu and trust translate into the happiest country in the world? Let’s start with trust.

Research by Paul Zak, founding director of the Center for Neuroeconomics Studies, shows that trust prompts people’s brains to release oxytocin, aka the “love hormone.” Not only does a brain awash in oxytocin make us feel better, but it also promotes prosocial behaviors and makes us feel more connected to others.

Here, Finland seems to have tapped into a happiness feedback loop. By seeing trust as a cornerstone of their national identity, they pursue communal accomplishments and social programs. Those prosocial behaviors deepened the pool of community trust, which promotes more prosocial behaviors. The output is happiness or, at least, more contentment in life.

As Minna Tervamäki, voted Finland’s most positive person in 2017, told the BBC: “I have very contradictory feelings about the happiness survey. Finnish people read it and laugh, like, ‘What? Us?’ What comes to my mind is that Finnish people are content more than happy.”

Sisu’s role in Finland’s happiness is more roundabout. That’s because, as positive psychologist Tal Ben-Shahar explains, people that pursue happiness directly often end up being less happy than those who don’t.

“If I wake up in the morning and say to myself, I want to be happy, I’m going to be happy no matter what, I am directly pursuing happiness,” Ben-Shahar writes in his book Happier, No Matter What. “This deliberate pursuit to be happy reminds me how important happiness is to me — of how much I value it — and therefore hurts more than it helps.”

By making sisu and not happiness their golden standard, the Finns don’t expect to be happy. They expect themselves to work hard to overcome whatever mental and physical challenges they face. And they expect that process to be difficult, open to failure, and a bit of pain now and then.

But in doing so, they turn their attention away from happiness and toward the pursuits that make life more meaningful. That generates more happiness than can be achieved if happiness is the direct goal.

“I don’t think there’s a point before one is unhappy, after which one is happy,” Ben-Shahar told us in an interview. “Rather, happiness resides on a continuum. It’s a life-long journey, and knowing that, we can have realistic rather than unrealistic expectations about what is possible.”

The happiest country is in the eye of the beholder

With all that said, a proviso: Happiness is a notoriously complicated emotion to study. Ben-Shahar defines it as wholebeing, a combination of whole person and well-being. But even he admits that this definition is designed to get at a type of happiness.

“Happiness is like beauty,” he writes. “You know it when you see it, or experience it.”

As psychologist Frank Martela points out, if the World Happiness Report looked at different metrics, they would receive different results. If they factored in GDP per capita — a flawed metric of happiness, but still — Luxembourg would be higher on their list. Had they weighed expressions of positive emotions more, Paraguay and Costa Rica would cinch it. And if they looked toward mental health, Finland would be paired with the U.S. as both countries have a similar share of the population with depression.

“What is vague and qualitative is open to many explanations,” Carl Sagan once wrote.

Given this, the lesson from Finland and the World Happiness Report isn’t that happiness is the Finnish way. We don’t need to fill our lives with saunas, reindeer sausage, and at-home drinking sessions in our underwear. (Unless you’re into it.) It’s not even that sisu is the be-all and end-all of happiness.

It is that happiness isn’t about perfection; it isn’t about living a gilded life free of worry and struggle. It is, at least in part, about finding the resilience to pursue the things that make life challenging and rewarding, and discovering ways to foster more trust among our neighborhoods and society at large. Whatever forms those pursuits may take are up to the individual, neighborhood, and society seeking them.

Who knows? That may allow other countries to end Finland’s reign as the happiest country in the world. A change that would probably make the Finns pretty happy, too.

Learn more on Big Think+

With a diverse library of lessons from the world’s biggest thinkers, Big Think+ helps businesses get smarter, faster. To access Tal Ben-Shahar’s full class for your organization, request a demo.