Is eudaimonic happiness the best kind of happiness?

- There are two types of happiness, hedonic and eudaimonic.

- While both support life satisfaction, research shows they serve unique purposes and are expressed in different brain regions.

- Eudaimonic happiness also appears to be more sustainable and seems to cultivate certain health benefits.

There’s a common perception that entrepreneurs and small business owners are overworked and stressed out. Both of those things can be true on occasion. At the same time, 94% of small business owners say they are happy with their lives, and 81% attribute this happiness to their entrepreneurship. The former value easily tops employees’ self-reported happiness. In a 2012 survey of 11,000 graduates of the Wharton MBA program, respondents running their own businesses ranked themselves the most content. “Entrepreneurship” even dominated “income” as a predictor of happiness.

The reason for this may be that entrepreneurship stokes a type of happiness called “eudaimonic happiness.”

There are two popular conceptions of happiness in psychology, hedonic and eudaimonic. You experience hedonic happiness through pleasure and enjoyment, like when scarfing down your favorite dessert, watching your beloved sports team win a big game, or hitting a jackpot in the casino. On the other hand, eudaimonic happiness is derived from activities that provide meaning or purpose, like volunteering for a cause you care about, raising children, or striving to make your business a success.

Both eudaimonic and hedonic happiness contribute to overall life satisfaction, but eudaimonic seems to provide a far more sustained effect. That’s because hedonic forms of happiness tend to provide only fleeting bursts of well-being, and the more hedonic activities you engage in, the more their positive effect on mood becomes muted. This partly explains why lottery winners generally aren’t significantly happier than people who have never won. After the initial excitement of winning life-changing wealth, their happiness mostly returns to baseline unless they utilize their newfound wealth to engage in eudaimonic pursuits — such as nurturing a hobby, starting an exercise program, or learning a language. These sorts of goal-driven activities, which realize personal talents and potential, evoke happiness that tends to stick around, raising overall well-being.

Again, all this isn’t to say that hedonic happiness is worthless. For a quick, mood-boosting pick-me-up, partying with friends or playing hours of mindless video games is fantastic. On the other hand, basing one’s well-being purely around hedonic happiness requires repeated, and often more stimulating, triggers. This is one aspect of what researchers term the “hedonic treadmill,” the observed tendency of humans to return to a fairly stable level of happiness despite experiencing positive or negative events.

Interestingly, cues of hedonic and eudaimonic happiness seem to stimulate different parts of the brain. In a 2019 study, researchers found that subjects in an fMRI brain scanner cued with hedonic events “showed enhanced activity in frontal medial/middle regions and anterior cingulate cortex.” On the other hand eudaimonic events prompted “increased activity in the right precentral gyrus.”

“Hedonic and eudaimonic happiness activate similar neural correlates. However, both kinds of happiness are also associated with distinctive brain areas serving distinctive functions,” the researchers wrote.

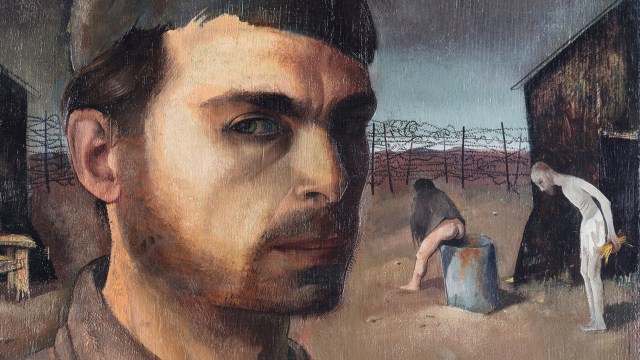

Another fascinating physiological difference between eudaimonic and hedonic happiness may arise in the immune system. In a 2013 study published to the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, subjects who characterized their lives as having “a sense of direction and meaning” had lower expression of genes tied to inflammation and higher expression of antibody and antiviral genes compared to subjects who described their happiness as more founded in hedonic pursuits.

Lead author Barbara Fredrickson of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, told Greater Good Magazine that there may be an evolutionary explanation:

“My guess is that eudaimonic pursuits build more and more helpful social resources relative to hedonic pursuits. So perhaps when hedonic pursuits become unbalanced by [too few] eudaimonic pursuits, our immune systems gear up for the same immune threats we’d encounter if we were lonely or otherwise socially isolated.”

This article was originally published on RealClearScience. It was written by Ross Pomeroy, a regular contributor to Big Think.