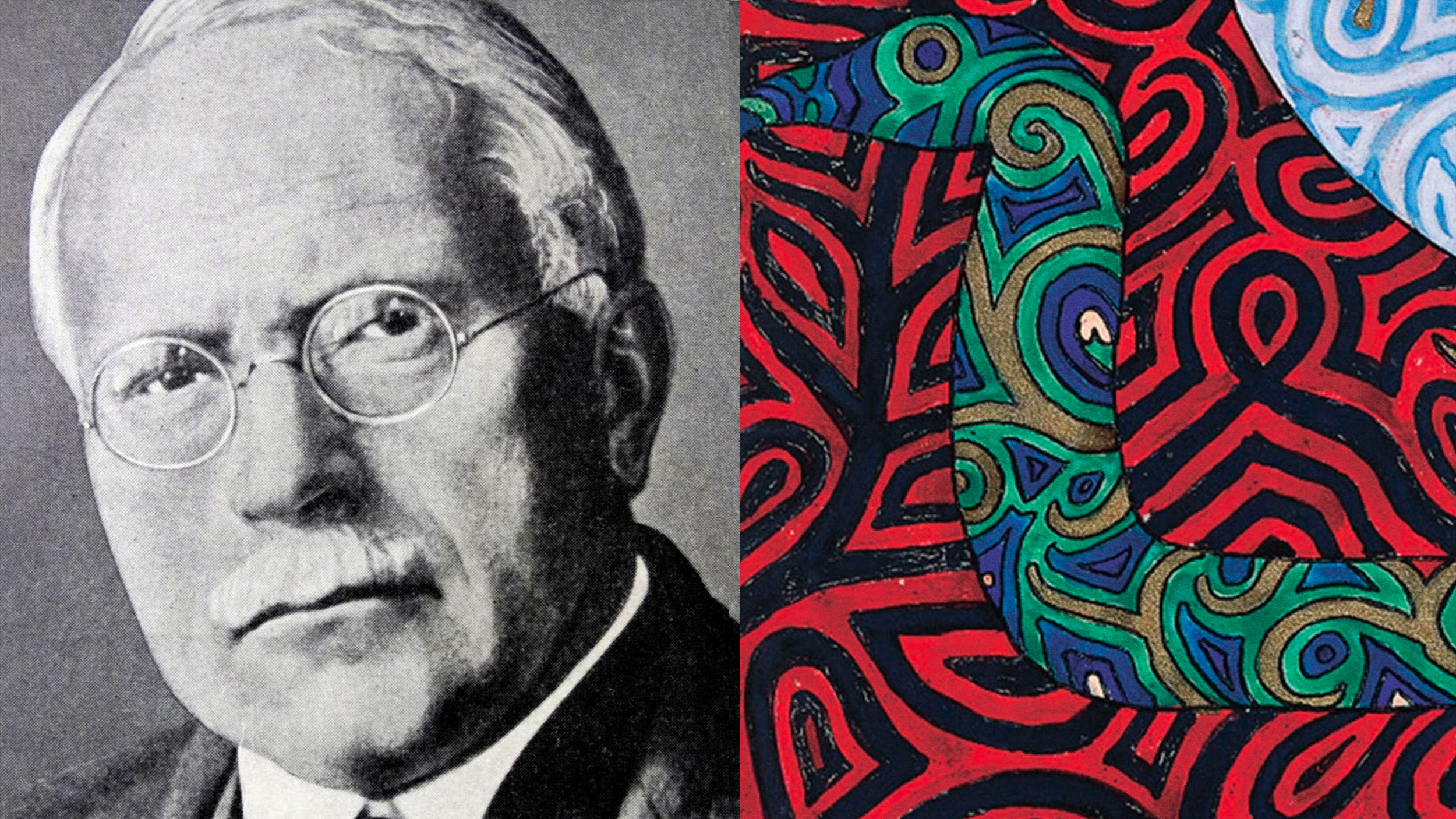

Mini-personalities: Why Carl Jung believed your “complexes” lead their own inner lives

- Carl Jung proposed that complexes are clusters of feelings, memories, and thoughts around specific emotional themes, often operating outside our conscious awareness.

- Effectively acting as autonomous entities, he believed complexes can influence our behavior and thought patterns.

- Jung suggested that by “assimilating” parts of the unconscious into the conscious mind, individuals could achieve better psychological balance and self-awareness.

“Wow, that’s probably been there for years,” once said a physical therapist as he ran a thumb over a hardened knot in my back. I was surprised. I had noticed muscle tension but never the particular knot that was contributing to it. The physical therapist said it could be causing tightness and mobility problems across my body in subtle yet significant ways.

A psychological complex — at least as the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung understood it — is a similar phenomenon. It is defined as a cluster of feelings, memories, and thoughts centered around a specific emotional theme that manifests like a knot in your psyche, often escaping your awareness such that it “behaves like an animated foreign body in the sphere of consciousness,” as Jung wrote in his Collected Works.

Like knots, he believed complexes can emerge from traumatic or stressful experiences. For example, someone who grew up with an emotionally absent and hyper-critical mother might — in their adult relationships, especially with women — oscillate between seeking maternal validation and fearing judgment, often projecting their unresolved emotions onto female peers and partners.

In a 1984 paper published in The Psychoanalytic Review, the psychotherapist John Ryan Haule outlined what Jung believed were the key characteristics of a complex:

- It has a sort of body with its own physiology so that it can upset the stomach, breathing, heart

- It has its own willpower and intentions so that it can disturb a train of thought or a course of action just as another human being can do

- It is in principle no different from the ego which is itself a complex

- It becomes dramatized in our dreams, poetry, and drama

- It becomes visible and audible in hallucinations

- It completely victimizes the personality in insanity

Illuminating complexes

Like much of Jung’s work, complexes have not been scientifically validated in the ways that other psychological concepts and tests have, like operant conditioning or the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. One reason is that it would be impossible to study complexes directly. Jung believed, after all, that complexes primarily exist in the personal unconscious, a subdivision of the psyche we cannot access directly in everyday waking life.

Still, Jung and other psychiatrists did conduct indirect experiments on complexes in the early 20th century. These were word-association tests where a participant was asked to listen to a series of 100 words — like “angry” and “family” — and to “answer as quickly as possible with the first word that occurs to your mind.” The researchers measured their response times. After repeating this process a second time, the researchers asked the participants about their feelings and thoughts toward the words to which they took relatively long to respond.

Whether these studies reveal anything useful about the nature or existence of complexes is debatable. Jung believed they did.

“This application of the experiment shows that it is possible to strike a concealed, indeed an unconscious complex by means of a stimulus word; and conversely we may assume with great certainty that behind a reaction which shows a complex indicator there is a hidden complex, even though the test-person strongly denies it.”

Today, Jung’s “analytical psychology” exists closer to the fringes of psychology than it does to the mainstream, though some clinicians still treat complexes as a psychological reality. It is maybe no wonder. The basic idea — that our lives can be influenced by a cluster of emotions and thoughts orbiting around a psychological theme — is something many people already treat as reality. You hear it in everyday conversations, like when someone says that a power-hungry short person has a “Napoleon complex,” or when someone jokes that the real reason a man leased a big, flashy car is to compensate for a natural, compact-class endowment.

But what’s less intuitive about complexes is the high degree of autonomy that Jung believed they can possess — as if they function like “mini personalities.”

Autonomous “splinter psyches”

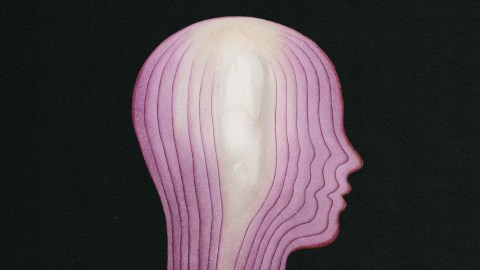

Jung dedicated his life to studying the nature of the self. He framed the self as both the center and totality of the psyche, which includes two broad realms: the conscious (the ego and the persona) and the unconscious (the personal and the collective). To Jung, the main aim of life is to develop a balanced psyche through individuation: the process of becoming the most complete and authentic version of yourself.

Individuation requires recognizing unconscious psychological content — including complexes — and lifting them to the conscious surface, a process Jung called integration. This is difficult, however, because Jung believed complexes splinter off from the conscious mind to “lead a separate existence in the dark realm of the unconscious, being at all times ready to hinder or reinforce the conscious functioning,” Jung wrote in his Collected Works.

Jung believed that complexes splinter away from the conscious mind because they originate from conflicts — like shock, upheaval, inner strife, and mental agony — and that we are unwilling or unable to assimilate the psychological fallout from these events into our conscious mind, or ego. As such, complexes are “‘skeletons in the cupboard’ which we do not like to remember and still less to be reminded of by others,” Jung wrote.

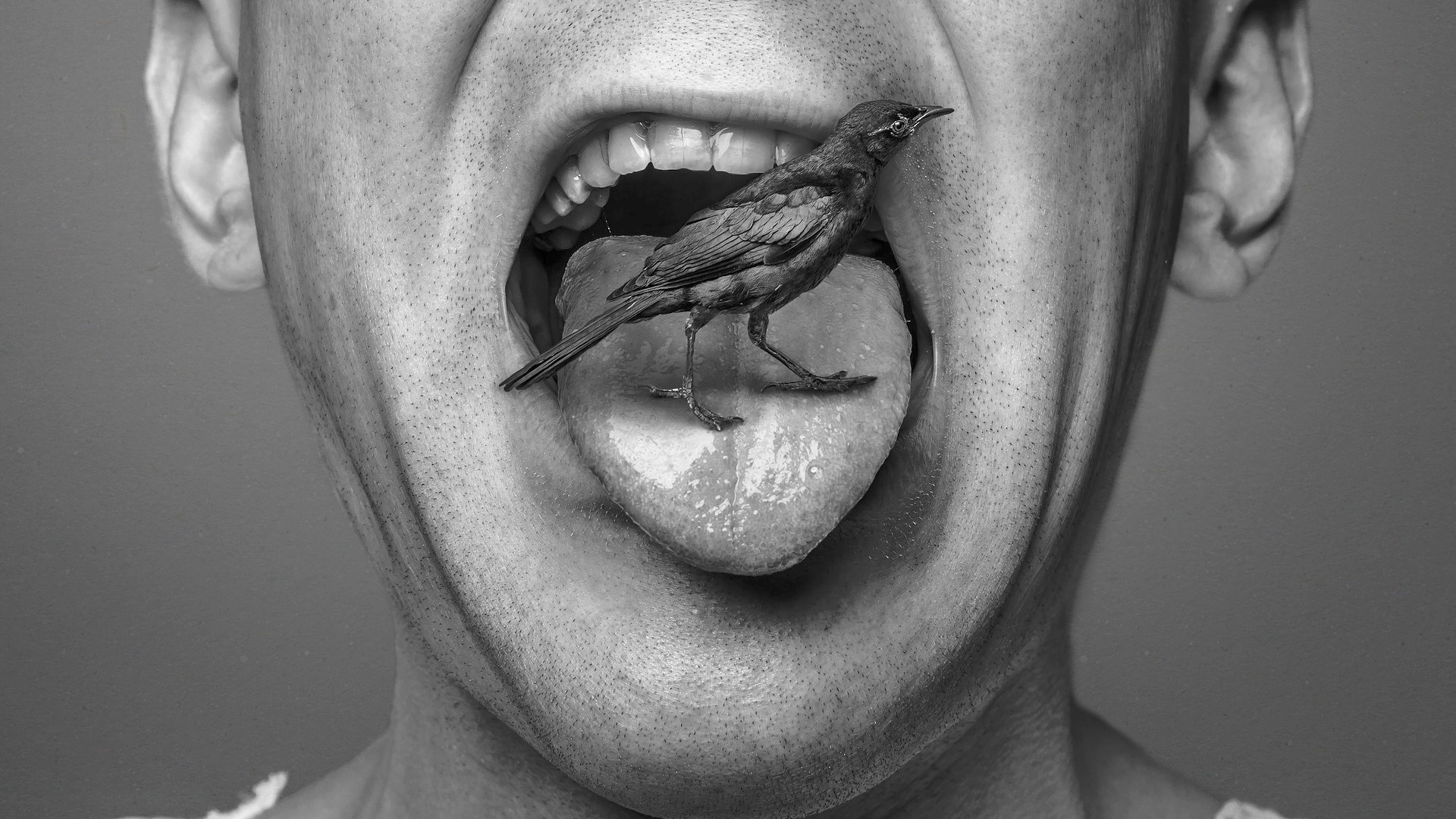

Often lurking below conscious awareness, he believed these tangled webs could lead autonomous lives. “The complex interferes with the conscious will and disturbs its intentions,” Jung wrote. “That is why we call it autonomous.” The therapist Richard Schwartz once described stumbling upon the existence of autonomous complexes, which he called “discrete and autonomous mental systems,” during a session with a 23-year-old patient with bulimia, who before vomiting would hear:

“…a confusing cacophony of voices that seemed to carry on conversations inside her head. When I pressed her to differentiate the voices, she found, to her own and my surprise, that with relative ease she could identify several voices that regularly participated in heated conversations with each other. One voice was highly critical of everything about her, especially her appearance. Another defended her against this criticism and blamed her parents for her problems. Another voice made her feel sad, hopeless, and helpless; and still another kept directing her to binge.”

“I found her inner life fascinating, both because her report was so similar to the reports of other bulimics I had treated, and because, as I listened to her, I became aware of somewhat similar voices within me.”

Still, other therapists, including some of Jung’s contemporaries, have criticized the description of complexes as “autonomous,” pointing to a lack of scientific basis. Jung wrote:

“The term ‘autonomous complex’ has often met with opposition, unjustifiably, it seems to me, because the active contents of the unconscious do behave in a way I cannot describe better than by the word ‘autonomous.’ The term is meant to indicate the capacity of the complexes to resist conscious intentions, and to come and go as they please.”

Complexes and the supremacy of will

The theoretical autonomy of complexes complicates the idea of free will: If unconscious forces can sometimes rise up and control our behavior — as described by people who “black out” in a fit of rage, or become temporarily “possessed” by a particular emotion — it is arguably more accurate to say, as Jung did, that we can not only have complexes but also “complexes can have us.”

“The complex must therefore be a psychic factor that, in terms of energy, possesses a value that sometimes exceeds that of our conscious intentions, otherwise, such disruptions of the conscious order would not be possible at all,” Jung wrote. “And in fact, an active complex puts us momentarily under a state of duress, of compulsive thinking and acting, for which under certain conditions the only appropriate term would be the judicial concept of diminished responsibility.”

On the extreme opposite side of becoming “possessed” by complexes were Jung’s experiments with confronting them face-to-face through active imagination, a meditation practice where he entered vivid daydreams and had conversations with the dream characters he encountered. Jung believed this practice enabled some form of contact not only with complexes but also with archetypes of the collective unconscious, which he described as an inherited layer of the psyche that houses universal patterns or symbols that humans can tap into (and often do through myths, art, and dreams). He thought this process could be therapeutic: By illuminating unconscious aspects of the self, you can diminish the ability of complexes to steer your thoughts and behaviors from the depths of your mind.

Jung readily admitted that such experiments reached beyond the realm of science and into that of literature, mythology, and theology. Complexes remain theoretical. Today, therapists outside of Jungian analysis and depth psychology might consider them to be fiction. Other disciplines also have different names for psychological concepts that are somewhat similar to complexes, like “schemas” in cognitive psychology or “core beliefs” in cognitive behavioral therapy.

To Jung, however, complexes were as real as knots in the back.

“Every human mind contains much that is unacknowledged and hence unconscious as such, and no one can boast that he stands completely above his complexes,” he said in a lecture. “Those who persist in maintaining that they can are not aware of the spectacles upon their noses.”