Progression bias: Your dating standards are likely lower than you think

- A 2021 review explored the existing literature on romantic relationships to see whether there is evidence for a so-called “progression bias.”

- The authors referred to progression bias as a tendency to make decisions that sustain relationships rather than dissolve them.

- The review suggests that people are far less selective than they might think, and that biological and social factors tend to make pro-relationship decisions easier for us than choosing to break up.

When you consider the obstacles a couple needs to overcome to form a serious romantic relationship, it is a wonder people end up together at all. To start a relationship, two people need to meet, find each other reasonably attractive and sane, overcome any first-date awkwardness, establish a bond, and agree to keep the relationship going. Sure, ending a relationship isn’t easy, especially when children are involved. But it seems more straightforward than building one.

One fundamental assumption underlying the idea that it’s harder to start a relationship holds that people are generally picky when dating. Whether it is having checklists or deal-breakers, people tend to conceptualize dating as a trial period for assessing their partner for a more serious long-term relationship. And it is, to some extent.

But a recent review suggests we might not be as selective as we think. Published in the journal Personality and Social Psychology Review, the paper offers evidence that people are more likely to make pro-relationship decisions at nearly every step of a relationship — from agreeing to a first date to maintaining a marriage — even at points where we might think our selectiveness would nudge us toward breaking up.

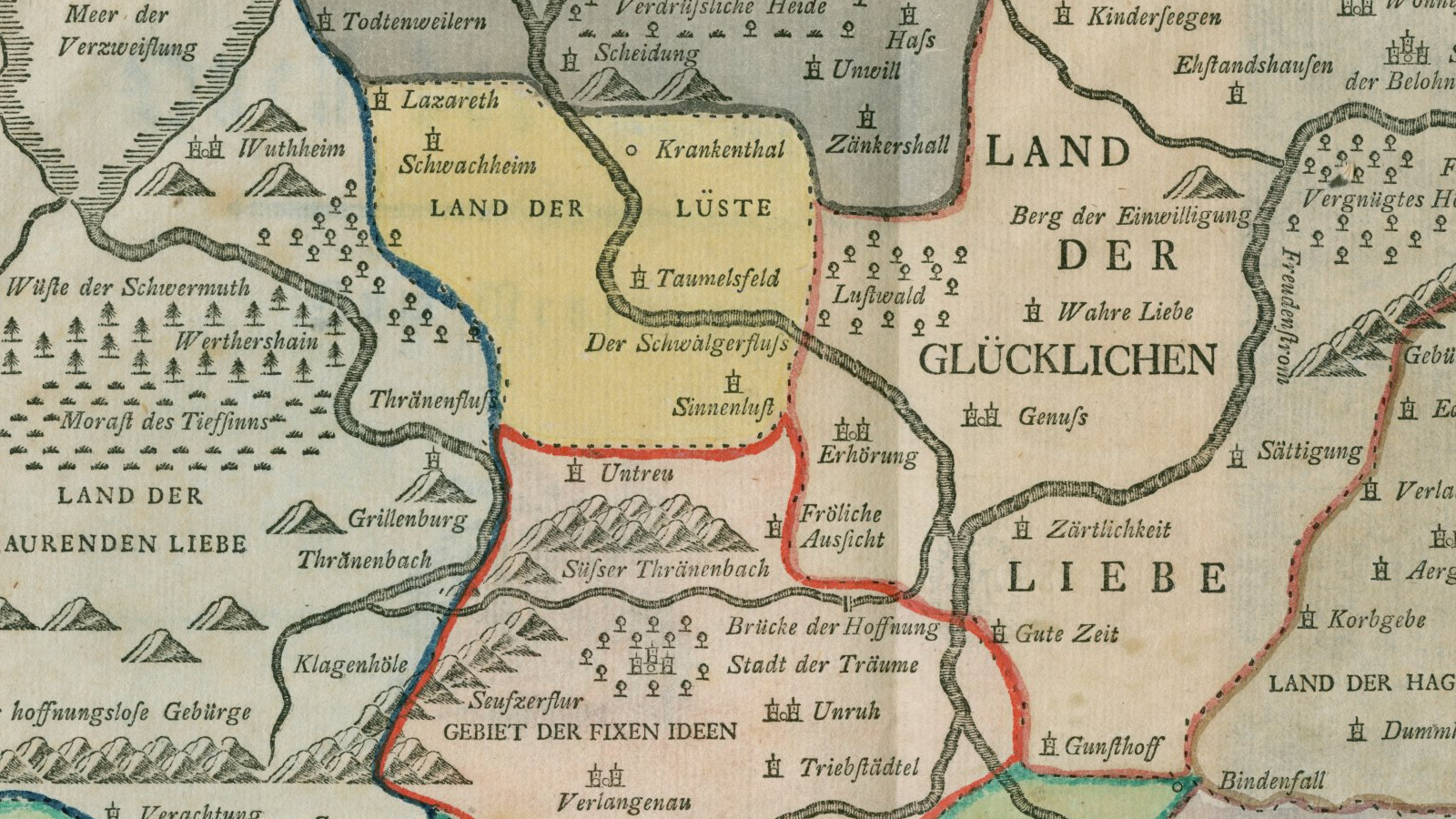

A progression bias in romantic relationships

The main thesis of the paper is that people have a so-called progression bias in romantic relationships, meaning they tend to make “decisions that serve to initiate, advance, and maintain romantic relationships” rather than choices that lead to “dissolution (e.g., rejecting or breaking up with suitors).”

The progression bias contradicts two common claims in relationship science. One claim says that people tend to make pro-relationship decisions only when the risk of rejection is low; the pain of getting turned down outweighs the potential benefits of pursuing a relationship. Another holds that people do tend to lean toward pro-relationship decisions, but only when the relationship is well-established, such as a married couple who chooses to work on their rocky relationship instead of giving up on it.

“We propose that, in fact, these [pro-relationship] biases are present as soon as any romantic interest has developed, such that they play an important role in propelling fledging dating partners toward established partnerships,” the researchers wrote.

Evidence for the progression bias

The paper reviewed dozens of studies within the existing literature on romantic relationships, finding evidence for the progression bias in three broad “turning points” in relationships: early-stage dating, investing in a relationship, and deciding whether to stay or leave.

In terms of early-stage dating (which includes choosing whom to date), the results of multiple speed-dating studies suggest that we are willing to date people who do not live up to our preconceived standards. Live interactions likely play a role in the process. For example, a 2011 study asked participants to evaluate written profiles of potential suitors and then meet in person. After the live interaction, the romantic interest expressed by the participants wasn’t associated with how well they matched with the suitors’ written profiles.

“In other words, although people discerned between potential partners who did versus did not meet their ideals when evaluating them ‘on paper,’ that selectivity vanished after a single interaction with the person,” wrote the researchers behind the recent review.

Not only are people less selective than they might think, but studies also suggest that we tend to form significant bonds with partners much earlier than previously thought — sometimes within a few months — and that these bonds continue to grow even when signs of incompatibility are clear. These emotional and psychological attachments tend to coincide with more logistical relationship investments: mixing social circles, moving in together, and getting married — decisions that couples often gradually slide into rather than pursue through conscious deliberation. Altogether, investments make breaking up increasingly difficult as the relationship grows.

Another factor that likely nudges people to make pro-relationship decisions is a lack of alternatives. For example, a 2019 meta-analysis found that a lack of appealing alternative people to date was, along with relationship investments, the top predictor of relationship commitment.

Why are we pulled toward pro-relationship decisions?

The review suggested that the progression bias is underpinned by a combination of biological and social mechanisms, among other potential contributors. On the biological side, sex, infatuation, and pair-bonding elicit physiological rewards that help reinforce our relationships, while also making it painful to end them. From a social perspective, it can pay to be in a relationship, whether that means pleasing your family, being perceived by your peers as having achieved an important life milestone, or avoiding the stigma of being single.

Albert Einstein once quipped: “Falling in love is not at all the most stupid thing that people do, but gravitation cannot be held responsible for it.” He was joking, sure. But within us there does seem to be a sense of gravity that constantly tugs us toward decisions that land us and keep us in long-term relationships, even if those relationships fall short of our preconceived ideals.

The review could not definitively determine whether that is because breaking up or being alone is too difficult or whether it is because humans are “satisficers—not maximizers—when it comes to mate search.” It is likely a combination of both, the ratio of which changes from person to person. What seems clear about relationships is that, at each fork in the road, choosing to keep it going is often the easiest option.

The researchers concluded:

“In sum, some theoretical perspectives and cultural narratives seem to portray daters as discerning consumers of the people they date. Dating is often conceptualized as a process of exhaustively searching through warehouses of potential partners, comparing each person’s qualities with a set of ideals and methodically rejecting or abandoning each option whose criteria do not match. We suggest that we might get closer to understanding the nature of human relating by considering that romantic connection has a certain gravity that is so far difficult for researchers to predict, but nevertheless compels the progression of romantic relationships.”