Mapping love: How 27 different types of love manifest in the body

- A research group at Aalto University in Finland conducted a study to explore how different types of love are experienced in various parts of the body.

- Surveying 558 native Finnish speakers, they identified 27 distinct types of love, which encompassed feelings for humans, non-human entities, and abstract ideas.

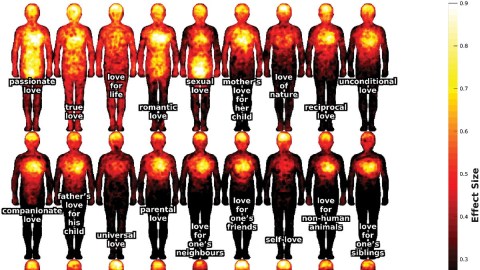

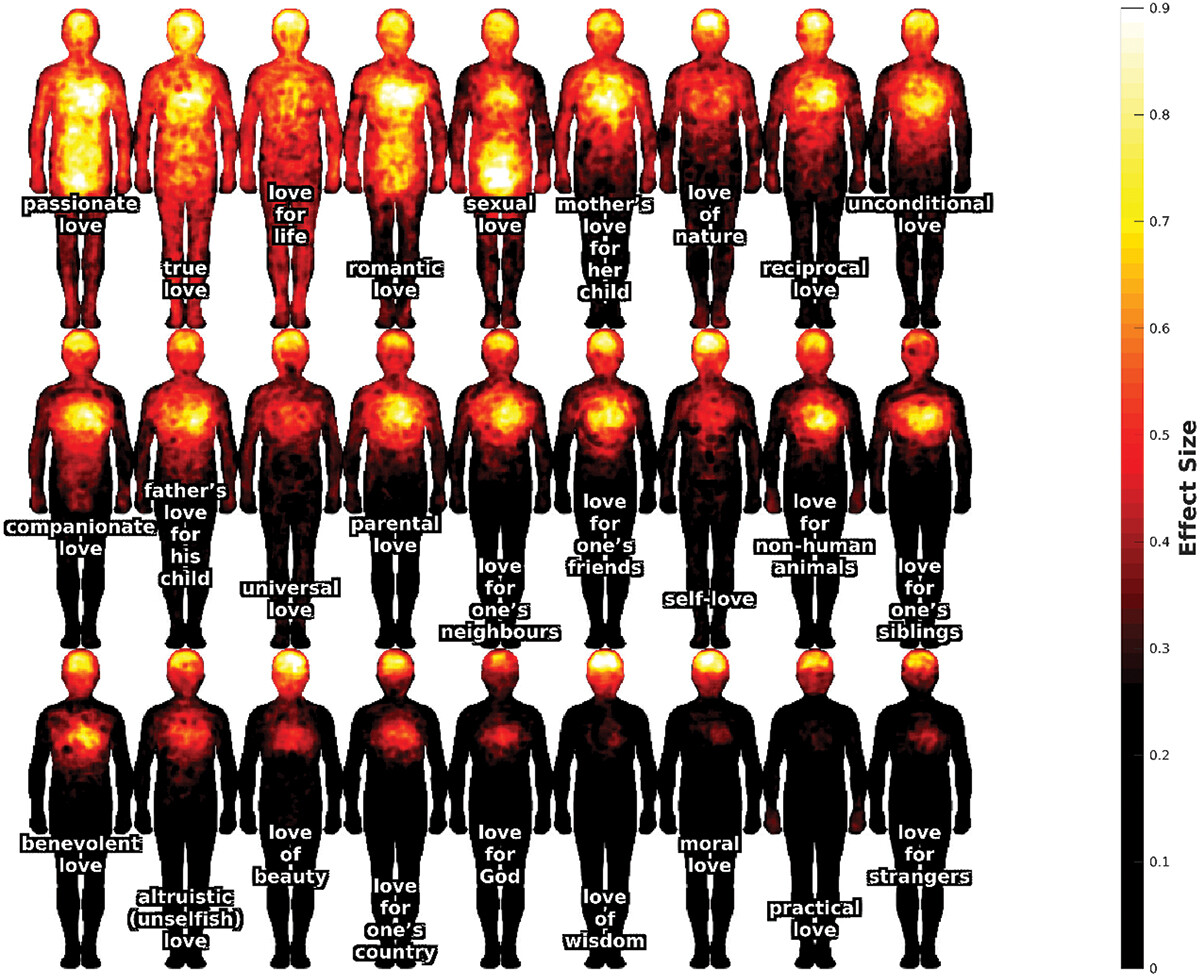

- The study revealed that while some types of love, like passionate love, were strongly felt throughout the body, others, such as love for wisdom, were felt less intensely and primarily in the head.

“All you need is love,” John Lennon once crooned. But what types of love do we experience, and where do we perceive them in the body? According to a recent study led by a research group at Aalto University in Finland, different types of love — from passionate love to love of animals to love of God — are experienced in different parts of the body, with varying degrees of magnitude and meaning. Given that the researchers differentiated and measured 27 specific types of love, it might be the case that “love” can be thought of as an umbrella term for a highly nuanced spectrum of human experience.

Mapping love across the body

For the study, published in Philosophical Psychology, 558 native Finnish speakers responded to questions about where they felt different types of love in their body, and how strongly and frequently they perceive these feelings in daily life. The 27 love types included feelings for humans (e.g. self, siblings, neighbors), non-human living objects (e.g. animals, nature), and ideas (e.g. wisdom, one’s country).

Why these 27 types in particular? Building on the “prototype theory of love” popularized by Beverley Fehr and other psychologists, the researchers maintain that the conceptual borders of love are indefinite or “fuzzy,” and that people tend to think of certain types of love as being more “prototypical,” or closer to the core of the concept (e.g. romantic love, parental love).

“We chose types of love known to be highly prototypical, and further included less prototypical types, which are nevertheless well known in philosophical and (Christian) theological literature,” Pärttyli Rinne, a visiting postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Neuroscience and Biomedical Engineering, and lead author of the study, told Big Think.

The goal of the study was not to identify and define every single type of love that humans experience, which would be difficult if not impossible given the subjective nature of love and the difficulty of defining these feelings through language alone. “We don’t believe in the construction of a rigid taxonomy for types of love: the plasticity of human experience and imagination ensures that, in principle, anything can be loved,” Rinne said.

Rather, the study aimed to answer three main questions about different types of love:

- Where are different types of love felt in the body?

- How are the feelings associated with different types of love related to emotional valence, bodily and mental experience, and controllability?

- How similar are different types of love in relation to each other, in body and mind?

The researchers conducted three experiments. One was a self-report task where participants colored feelings of love onto a rendering of a human body on a screen. Another involved showing participants terms for different love types on a screen in random order and then asking them how strongly they felt each type in the body or mind, how pleasant each type felt, the extent to which they could control each one, and other questions. A third task asked participants to rate how similar the love types were to one another.

Topographically, different love types seemed to manifest in different parts of the body, and in different levels of strength. True love, passionate love, and love for life were experienced most strongly in the body. Meanwhile, love for wisdom, moral love, and practical love were experienced relatively weakly. In general, the strongest love types were experienced widely throughout the body, and all love types were felt in the head.

Love types in varying strengths and locations

“We didn’t expect that all the love types would be felt in the head,” says Rinne. “In general, feelings of love are more prominent in the upper body, but chest area activations wane when we move from more strongly felt to more weakly felt loves. Why are even the most weakly felt loves such as love of wisdom, moral love or love for strangers nevertheless felt in the head? Maybe people associate these types of love with rational thinking or deliberate cognitive processes, or maybe there are pleasant sensations in the head, perhaps pleasant thoughts. This should be investigated further.”

The interpersonal love types felt most strongly in the body were true love and passionate love. The strongest “nonhuman” love types were love for life and love for nature. The weakest interpersonal love type was love for strangers, while the weakest type for ideas was practical love. Interestingly, love for life and love for nature scored as highly as love for family and friends overall, and more highly than love for self. Although self-love was rated as the most controllable love type, participants reported experiencing it infrequently compared to less controllable love types like family and friends.

The only case where love for self was felt more strongly than love for life and nature was under the “touch” measure, perhaps hinting at the social nature of self-love.

“It appears that in love, salience, valence, and the dimension of touch go hand in hand,” Rinne says. “The strongest feelings of love appear in close interpersonal relationships. Prototypically, love indicates that the positive feeling associated with the interpersonal relationship is subjectively very important, highly pleasurable, and involves physical intimacy (not necessarily sexual). The more weakly felt and abstract types of love are less associated with physical touch.”

Indeed, the results suggest a link between mind and body in more ways than one.

“What’s interesting [about the results] is that there was a very strong correlation between bodily salience, mental salience, and valence — that is, the more strongly a type of love is felt in the body, the more strongly it is also felt in the mind, and the more pleasurable it is.”

The study represents a step forward in the scientific understanding of love, which Rinne says has been shortchanged by the sole focus on romantic and parental love in both neuroscience and psychology research.

“Considering how important love is for human life and culture, there is still surprisingly little scientific knowledge of love. We hope to contribute to the growth of the science of love, not only to promote theoretical understanding, but also to facilitate public, cultural discussion.”