Should you get your PhD?

You’ll be investing 5-to-7 years of your life. What will you get back?

“An investment in knowledge pays the best interest.” –Benjamin Franklin

Recently, a number of people — of widely different ages and levels of education — have contacted me for advice on whether or not pursuing a PhD in astrophysics, physics or science-in-general is right for them. This is the season of acceptances, rejections and big decisions, after all. Of course, I can’t tell you whether a path is the right one for you or not, but there are certain questions I think everyone should ask if this is, in fact, something you’re considering. It’s a difficult proposition that requires you be honest with yourselves in ways we don’t often think about.

I’m going to be speaking mostly from my own experiences, both from what I’ve lived and from my peers, mentors and students, but I think this might be of interest to a broad audience as well.

First off, there are many, many bad reasons that people think of when it comes to getting a PhD. Here are some of the most common that I’ve run across:

- Do not get a PhD in science (or any field) because you think it will make you smarter. It won’t. A degree — a piece of paper — never made anyone smarter, and you are not the exception. You will gain some skills and knowledge, but those won’t make you smarter, and likely won’t make you even feel smarter.

- Do not get a PhD because you think being a professor would be a great career choice. Getting a PhD is no guarantee that you will get a professorship, and even if it were, the promise of this future reward is not enough incentive on its own.

- Do not go after a PhD because you have dreams of money or glory or respect. Any of these accolades are rare for PhDs, and those that get them almost universally were recipients of a tremendous amount of luck in addition to whichever of their talents and merits were honed and cultivated by their PhD work.

- Definitely do not pursue a PhD because you majored in something in college, you don’t know what to do next, and graduate school seems like the next logical step.

It may seem obvious to you that these are bad ideas, but let me elaborate a little further. A PhD is not evidence that you are a genius. In fact, the vast majority of people with PhDs are not of any extraordinary intelligence, but merely people who did the hard work necessary to earn a PhD.

There are plenty of brilliant people who get them, of course, but there are also plenty of people of average or even below-average intelligence who get them. All a PhD signifies, at the end of the day, is that you did the work necessary to earn a PhD. There are many people who have PhDs who will dispute this, of course. There are plenty of people who are insecure about their lives, too, and base their entire sense of self-worth on their academic achievements and accolades. You probably have met a few of them: they are called jerks.

Image credit: Warner Bros. Pictures.

Being a professor is a great job in many ways. It’s certainly one of the most competitive jobs out there: the last time I was on a hiring committee, we had over 200 applications — from qualified, job-hunting PhDs — for a single opening. Jon Katz is very pessimistic about your chances at landing a permanent professorship, and he’s not wrong. But the hope of a job some ten years down-the-road is a horrible reason to embark on an endeavor of this magnitude. I’m also one of the rarest breeds out there: someone who was a professor, was offered a tenure-track position, and turned it down. You get just one life, and there are no do-overs. If you get to the end and you haven’t lived it the way you want… whose fault is that?

There are a few PhD scientists who have become rich, powerful, and famous. But if you’re pursuing a PhD in science because you want to be rich, aren’t there about a bajillion careers out there that are more lucrative?

If you want to be powerful, do you really think a PhD will help with that?

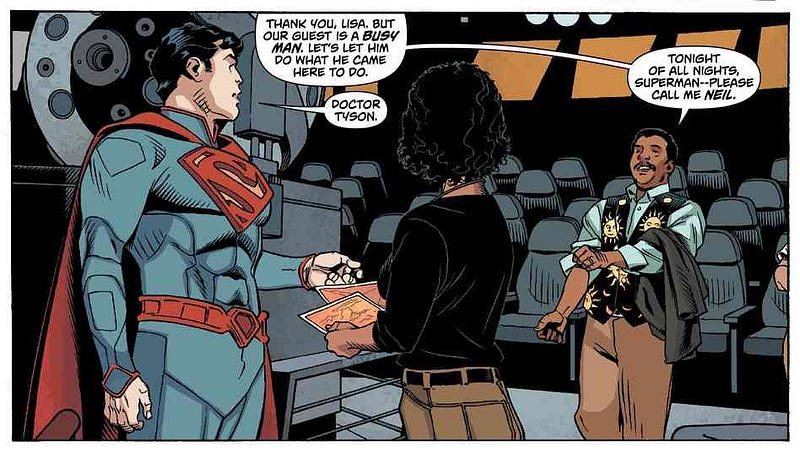

If you want to be famous, can you name even five famous living scientists? (And if you name me, you automatically lose.)

If you want to be the next Nobel-prizewinning physicist, the next Carl Sagan or Neil de Grasse Tyson, or the next Albert Einstein, you’re more than welcome to try. While a PhD might be a de facto requirement to achieve those things (although, surprise, Neil didn’t get one on his first try), it certainly isn’t any sort of guarantee to get you there.

And this last one — the “I don’t know what to do next so I guess I’ll try grad school” — is the most common cause of grad-school-burnout I’ve ever seen. This isn’t to say that there aren’t some people who enter grad school with this mindset and wind up doing very well for themselves; I’ve known a few who’ve graduated with their PhDs and went on to some substantial amount of success. But there’s no better recipe for getting a graduate student to quit graduate school than putting someone who doesn’t have the right internal motives into that situation in the first place.

Now, in every scientific field, graduate school requires a tremendous amount of hard work to get your PhD. Mine — in theoretical astrophysics/cosmology — came through a physics department. This pretty much requires:

- Acceptance into physics graduate school, which in itself requires:

- -Either a bachelor’s in physics or the equivalent coursework, which is a year of introductory physics, at least two semesters of quantum mechanics, two semesters of advanced E&M, two semesters of advanced classical mechanics, two semesters of advanced laboratory courses, a smattering of advanced special-topics courses (thermo, astro, nuclear/particle), and math up through Fourier series and complex analysis. [Note: many smaller colleges do not even offer these courses; you will likely have to spend a semester-to-a-year remediating yourself in grad school if you’re deficient in any of these!]

-Research experience isn’t normally a stated requirement, but at least a few summers/semesters’ worth is highly preferred.

-You also need good score on both the Physics and the general GREs.

-And three solid letters of recommendation. - Success in the first-year “core” courses, which is a year of graduate E&M, a year of graduate Quantum Mechanics, and a half-year each of Statistical Mechanics and graduate Classical Mechanics.

- Success finding an advisor who’s a good match for you. That means someone who you not only enjoy working with and who works well with you, but someone who is interested in the same sub-specialty of your discipline as you.

- Success in the advanced coursework and in advanced research, both directed and independent. This likely includes a substantial amount of computer programming; if you haven’t learned it by now, you’re going to have to, and fast.

- Success in writing your own scientific research papers, and getting them published.

So, what determines whether you’ll achieve this success or not? The biggest determiner of success that I’ve found is this: how big is your internal motivation to learn the thing you’restudying?

Because even though some expectations are absurd, you are going to have to work extremely hard to become proficient at thinking about some aspects of the world in an entirely different way. You’re going to have to put in years of studying, reading, research, problem-solving, meticulous, detail-oriented work, and the only person you’ll be accountable to is yourself. (Yes, your advisor will care, too, but not enough to make up for your lack-of-motivation if you don’t have it yourself.) If you can’t find that motivation to learn this inside of you, if you can’t find the motivation to work this hard for, on average, five-to-seven years in graduate school, then a PhD is not for you.

That’s the number one question you should be asking yourself, in my opinion, if you’re thinking about getting a PhD in a scientific field:

- Is there something that I need to learn so bad that my life will be incomplete if I don’t go and learn it for myself?

That was my experience. There is another option, too, that I’ve heard from quite a few people, including my advisor:

- Is there something that I enjoy doing so much that I can’t imagine doing anything else as long as I can keep doing this?

If you answered yes to either of these two questions, then it will likely be worth it to you, and you should go for it! It will be hard, it will be a lot of work, you will not be guaranteed a job, wealth, success, a professorship, a Nobel Prize, self-confidence, true love, or any other false idols.

But you will have learned something that you’ll always carry with you the rest of your life, and that no one can take away from you. You will have invested in your own knowledge, and you’ll have the rest of your life to enjoy the fruits of that tree, whatever directions it may grow in. I’ve known people get their PhDs in their 20s, and I’ve known people get them in their 50s, with both groups going on to success. (So don’t let age dissuade you!)

If you can dream it, you can be it, so what are you waiting for?!

Recommended further reading:

- Jonathan Katz’s Don’t Become A Scientist!

- Katie Mack’s Advice for Aspiring Astrophysicists

- My Advice for Aspiring Young Scientists

- What my readers Wish They Knew When They Started College

- Your First Year In Physics Graduate School

- What You Shouldn’t Put Up With In Grad School

- and for those of you who’ve almost made it, The Untold Secret to Writing Your Dissertation

An earlier version of this post originally appeared on the old Starts With A Bang blog on Scienceblogs. Leave a comment on our forum there!