The Two Big Bangs

Is it how the Universe began, or just how our observable Universe began? They’re not the same!

“These theories were based on the hypothesis that all the matter in the universe was created in one big bang at a particular time in the remote past.” –Fred Hoyle

When you think about how the Universe got its start, from a scientific point of view, there’s one theory that explains what we see above all others: the Big Bang. But not everyone agrees on what “the Big Bang” actually means. In particular, there’s always some news that periodically goes around claiming that perhaps there was no Big Bang, after all. Is this legitimate? And if it is, what does it mean, exactly?

To understand this, let’s go back 100 years, to the very first time we decided to look at a certain class of object — the faint spiral and elliptical nebulae in our skies — in any sort of detail. Today, it’s easy to look at these objects and say, “oh, those are galaxies!” But a century ago, it wasn’t so clear. Our telescopes were not good enough to resolve these objects into the individual stars that make them up, and so they were simply thought to be a type of nebula. But there was one thing that was awfully bizarre about them: their speeds.

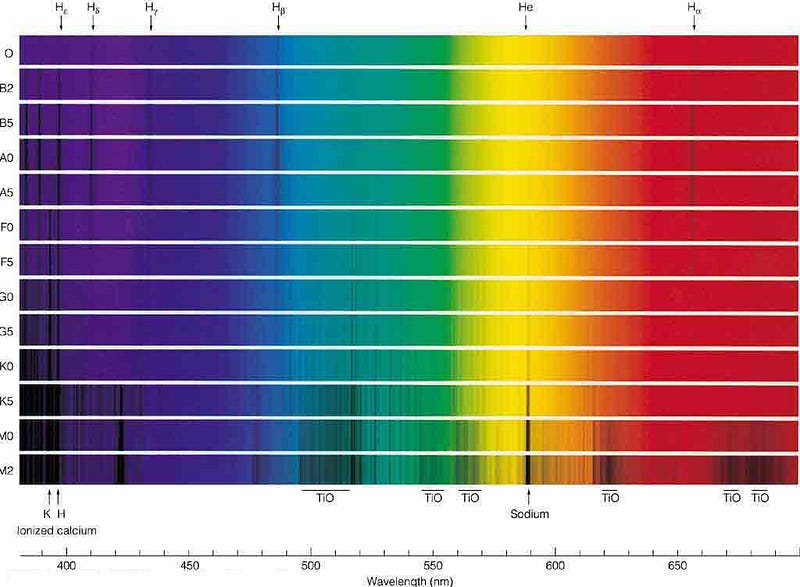

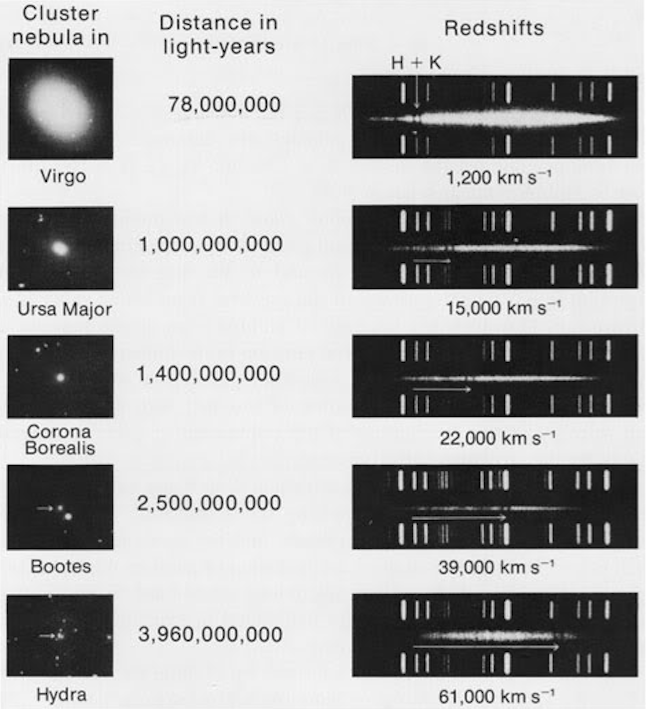

You see, every element has its own characteristic spectrum — a set of lines that it either absorbs or emits — and that spectrum is fixed at a certain set of wavelengths. Hydrogen, for example, always exhibits lines at 656, 486, 434, and 410 nanometers, each of which corresponds to a specific atomic energy transition. When you look at a star (or galaxy), you’ll see this set of absorption lines that correspond to the various elements with various absorption properties inside.

But in these spirals and ellipticals, the absorption lines you expected all were present, but they appeared in a bizarre fashion: severely shifted from normal.

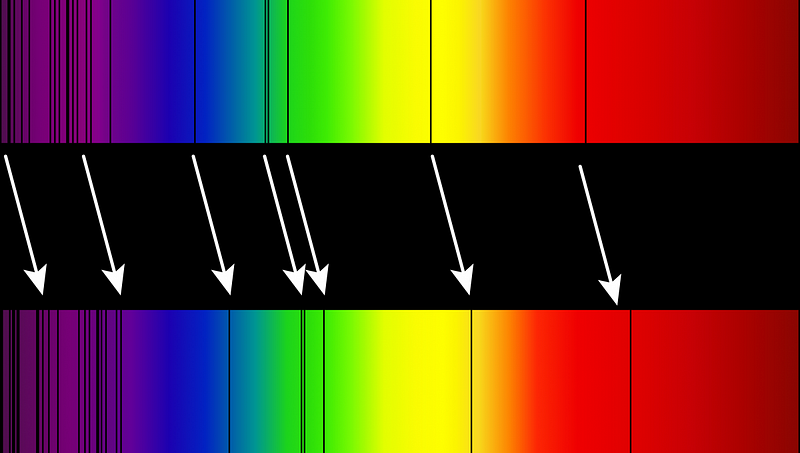

The simplest explanation? Not some new type of element or some new type of physics inherent in each one of these nebulae, but rather that these objects were moving rapidly, either towards us or away from us. Just as any sound — from a police siren to an ice cream truck — will have its pitch change if it’s in motion either towards us or away from us, a distant object will have the wavelength of its light appear to shift depending on whether it’s moving towards us or away from us.

If it moves towards us, the light gets shifted towards the blue; if it moves away from us, the light gets shifted towards the red. In the early 20th century, Vesto Slipher found that the vast majority of spirals out there were shifted towards the red, and were shifted so much that they were moving faster than anything else in the known Universe!

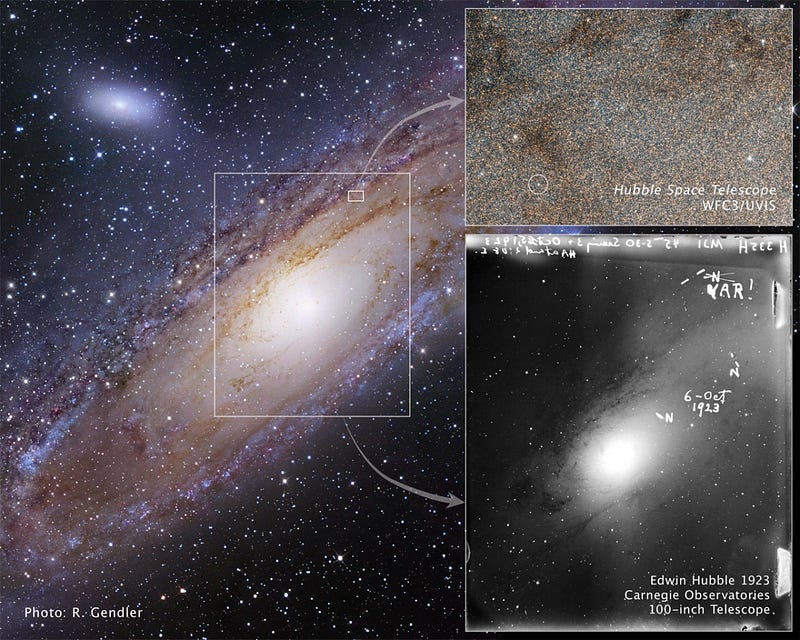

But it was in the 1920s that someone really began to put this puzzle together. Edwin Hubble — whom the famous telescope is named after — was observing “flare-ups” in these individual spirals, looking for events like novae. Much to his surprise, while looking at Andromeda, he saw one, then a second, then a third. But then, he saw a fourth in the same location as the first! He immediately realized this was no nova, but rather a variable star. Since variable stars were understood, he could figure out how distant this object was, and concluded it was well outside of our own galaxy.

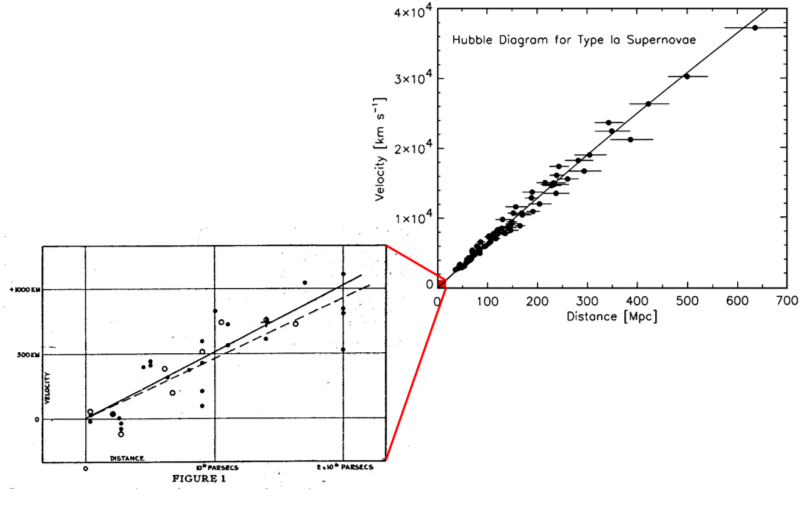

Of course, once he realized there were variable stars in one of these spirals, Hubble didn’t stop there. He went on to measure the distances to dozens of other galaxies, and when he combined that data with Slipher’s velocity data, he found something remarkable: on average, the farther away a galaxy is, the faster it’s moving away from us. The expanding Universe was born.

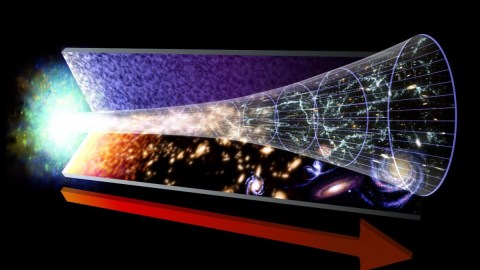

In the context of General Relativity, spacetimes that are full of matter or radiation in many different locations — spacetimes like ours — don’t do a good job of remaining static over time. They either expand or contract, depending on how much energy is in them. What we observe is that our Universe is expanding today, from a state that was more dense in the past.

It also means, because the amount of energy that light (radiation) possesses is dependent on its wavelength, that if the Universe was smaller in the past, it was also hotter and higher in energy in the past.

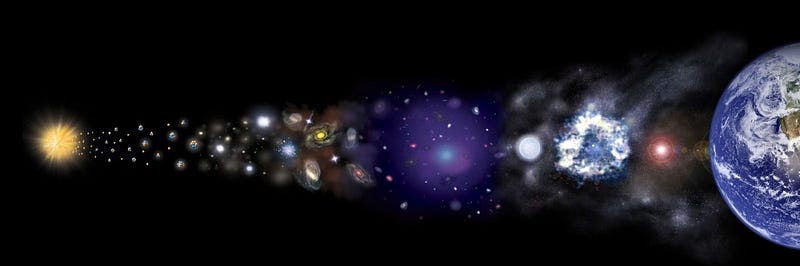

Shall we extrapolate that backwards? Imagine that the Universe exists as it does today, but we make it smaller and hotter in the past. What would things have been like if we’re willing to go far enough back?

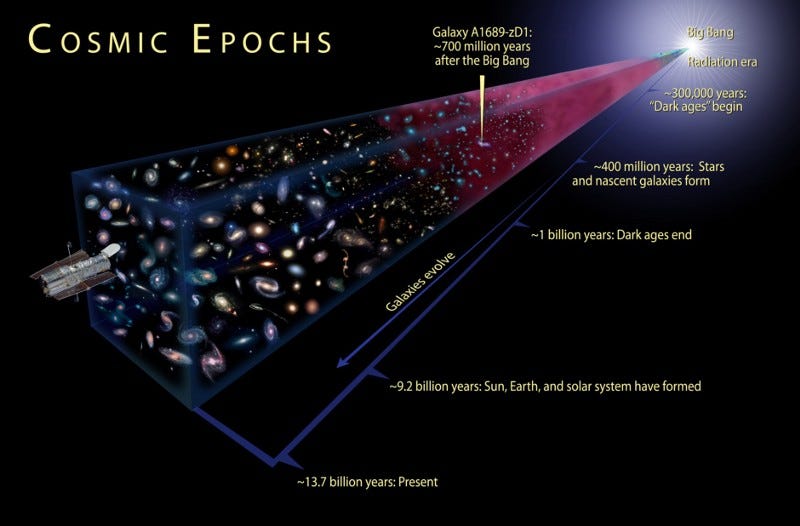

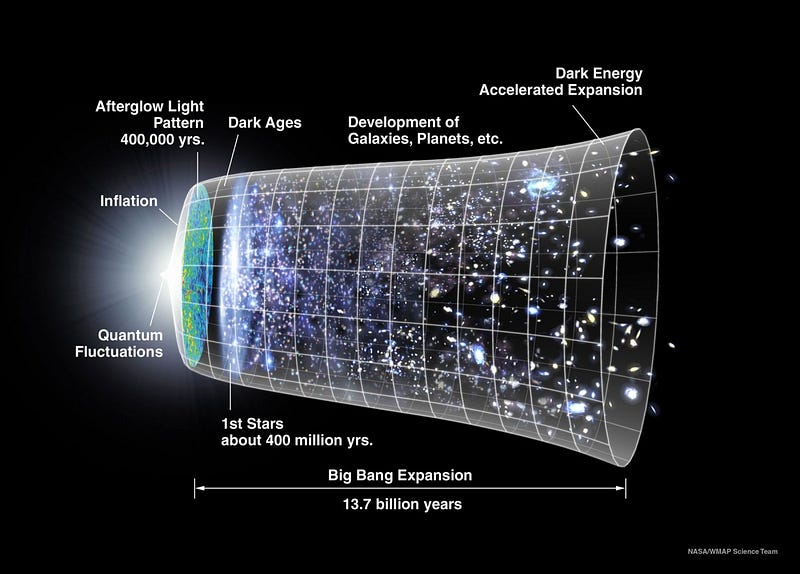

- Eventually, it would have been so hot and dense that atoms themselves would have been unable to form; everything would have been a hot, ionized plasma early on.

- Even earlier than that, atomic nuclei would have been unable to form; individual protons and neutrons would have been blasted apart, creating a sea of free particles with no elements other than hydrogen.

- Before that, matter and antimatter would have been spontaneously created in pairs, giving rise to all the known (and potentially even some hitherto undiscovered) particles in the Universe.

- And finally, if we go all the way back to a time where things were arbitrarily, perhaps even infinitely hot-and-dense, we come to a singularity: a place where all of time, space and energy condensed into a single point.

This idea — that everything emerged from a “cosmic egg,” a “primeval atom” or an “arbitrarily hot, dense state” — is what we know today as the Big Bang.

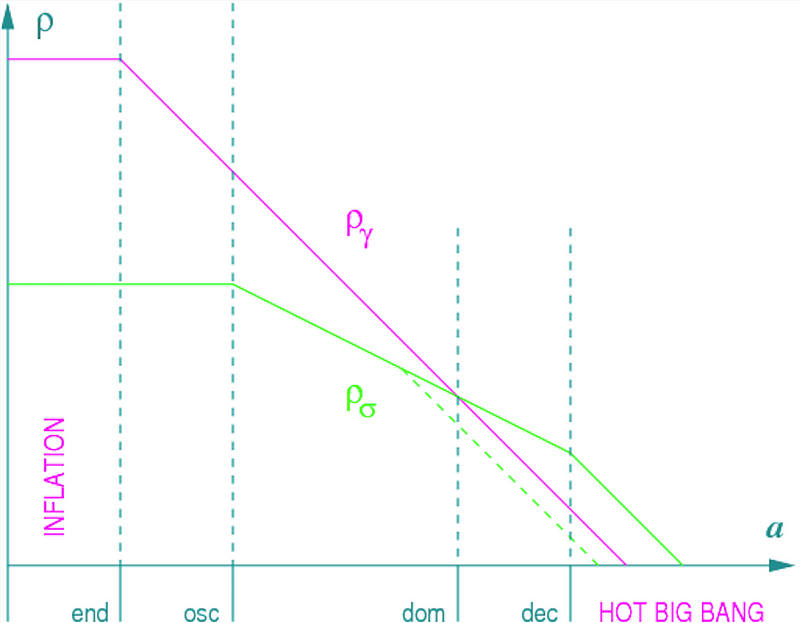

Only, this was the original definition of the Big Bang. We’ve learned quite a few things about the Universe since this idea was first proposed. In particular, we’ve learned that in addition to matter and radiation, the Universe also contain an amount of energy inherent to space itself, or dark energy, or cosmological constant, or vacuum energy (all synonyms).

It contains a relatively small amount of this now, but it contained a fantastically large amount of this energy early on.

That’s right: prior to being dominated by matter-and-radiation, the Universe was dominated by energy inherent to space itself, a theory first put forth in the late 1970s/early 1980s, and first confirmed observationally in the early 1990s. When you hear about cosmological inflation (or the inflationary Universe), this is what we’re referring to: a time when the Universe wasn’t dominated by matter or radiation, but by energy inherent to space itself.

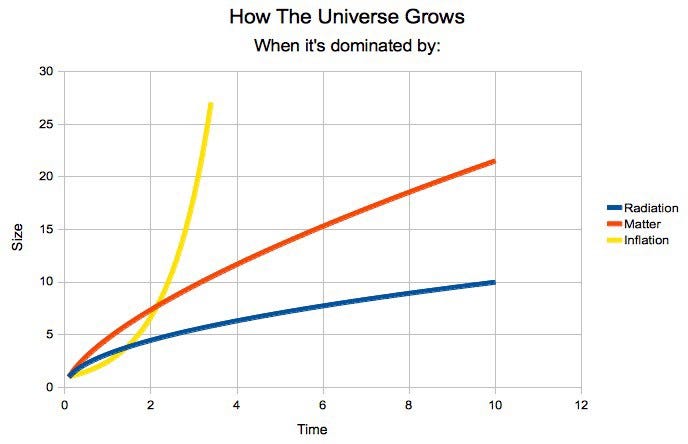

And Universes dominated by vacuum energy, or by inflation, evolve differently than those dominated by matter or radiation.

Sure, it might look like these Universes differ only in detail, but they all expand at a given rate from a certain starting point.

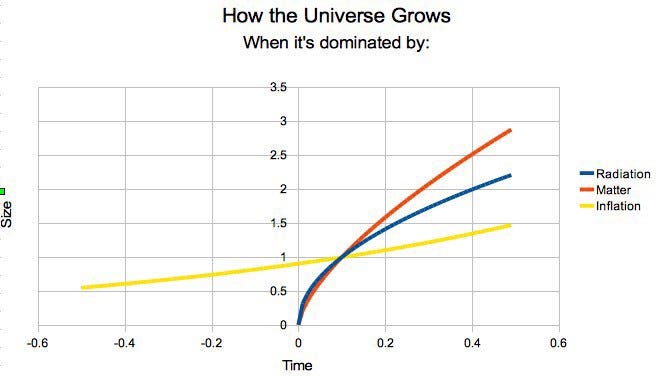

Or do they? Let’s look closer at the “very beginning,” and this time, let’s not restrict ourselves to stopping near that (0,0) point at the origin.

While a Universe that’s dominated by matter or radiation will, in fact, come from a singularity, from a moment where space and time themselves first emerge, there is no such moment like that for an inflationary Universe.

In other words, that last point that we intuited — that there would be a place where space and time first emerged — is not necessarily a part of the “Big Bang” if your Universe contains an inflationary phase at the beginning.

When cosmologists — that’s the sub-field of astrophysics dealing with the origin and evolution of the Universe — speak about the Big Bang, they mean one of two things:

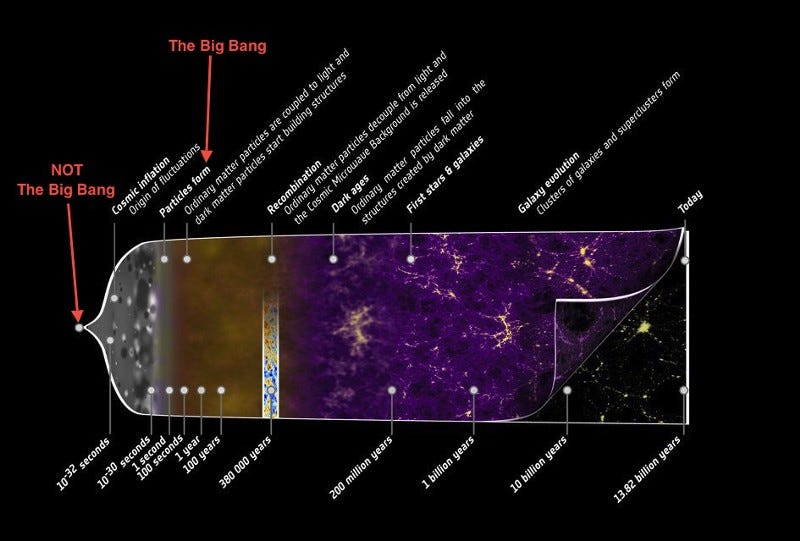

- The hot, dense, expanding state that our observable Universe emerged from, that expanded, slowed, cooled, and gave rise to elements, atoms, stars, molecules, planets, and eventually us.

- The initial singularity that represents the birth of space and time.

The only problem is, while these two explanations were interchangeable back in say, the 1960s, they no longer are.

The first explanation — the hot, dense, expanding state — still makes sense as “the Big Bang,” but the second one no longer does. In fact, as far as the question of where space and time come from goes, there is still plenty of debate on all sides, and whatever recent papers come out are simply another drop in the ocean of that debate: nothing more.

The biggest thing you should learn from all this? That “the Big Bang” represents where everything we see in the Universe comes from, but it is not the very beginning of the Universe anymore. We can go back before this explanation is any good, to an inflationary Universe, and we have good reasons to argue over and debate the finer points of what, exactly, that means for the ultimate origin of everything we know.

But did the Big Bang happen? By the first definition, yes, absolutely: the Universe emerged from a hot, dense, uniform and rapidly expanding state, and has been cooling and getting less dense ever since. But if you’re using the second definition, you may really want to rethink using the term “the Big Bang.” You won’t be the only one using it that way, but your assumptions — and your conclusions — might be completely wrong.

Leave your comments on our forum, and check out our first book: Beyond The Galaxy, available now, as well as our reward-rich Patreon campaign!