Who Stole Oswald’s Stone, the Magic Middlesex Monolith?

Millions live in or near Ossulstone, but only a handful have ever heard of it. Why and how has this place disappeared from common memory? Perhaps the when is easier to trace – to 1869, the year in which the mysterious object that lent its name to the area was stolen.

Marking the intersection of two ancient London roads [1], at a place formerly called Tyburn but now known as Marble Arch, a monolith called Oswald’s Stone once stood. Until 1783, Tyburn was the place for public executions in London [2]; undoubtedly in part to erase that location’s lurid reputation, it was chosen as the relocation site for a large monument that was deemed out of place in front of Buckingham Palace [3].

Ossulstone, with its 4 constituent districts (Kensington, Holborn, Finsbury and Tower divisions), 2 territorial exceptions (the City of London and the City and Liberty of Westminster), and the area annexed by London in 1889 (in grey). [Image taken here at a website for the Oliver-Paull family tree]

Nobody remembered what the stone was meant to mark [4] or even who Oswald was. Indeed, the rock was also called Oswulf’s Stone. Unsure about what to do with the ancient monolith, the authorities interred it in 1819 – only to dig it up again in 1822. In later years, it was found leaning against Marble Arch. After an archeological journal highlighted its historical importance, Oswald’s Stone disappeared. It has never been seen since that fateful day in 1869.

Presuming that the stone was removed by someone alerted to its value by the archeological article, it is not unthinkable that someone somewhere, perhaps a descendant of that 19th-century thief, is still holding Oswald’s Stone. Although, judging by the facility with which the last remnants of ancient names and meanings vanish from knowledge, perhaps he or she no longer knows why that stone was so important to great-grandpa.

The historical County of Middlesex, bounded by three rivers, and the Grimsdyke. [Image taken here from Antique Maps Online]

I accidentally stumbled across Oswald’s Stone – figuratively speaking of course – while looking for an answer to a question that had bothered me for some time: Where is Middlesex? Half a dozen Middlesexes survive as place-names in the US, Canada and Jamaica. But the original Middlesex [5], once one of England’s counties is defunct: small enough to begin with, it had the additional bad fortune to be encroached upon by London, and in the end be gobbled up piecemeal by the metropolis. The last vestiges of the county, whose name was first attested in 704 AD, were abolished on 1 April 1965, when nearly all that remained of Middlesex became part of Greater London [6].

Middlesex may be dead, but it is not entirely forgotten: it leads a phantom existence in the names of Middlesex University, the Middlesex County Cricket Board, and the Middlesex County Football Cup. There’s even a Middlesex County Day (May 16th [7]) and a Middlesex County Flower (the wood anemone). You can still address letters to a number of postal towns [9] by adding Middlesex to the address, but adding the county is no longer required by Royal Mail.

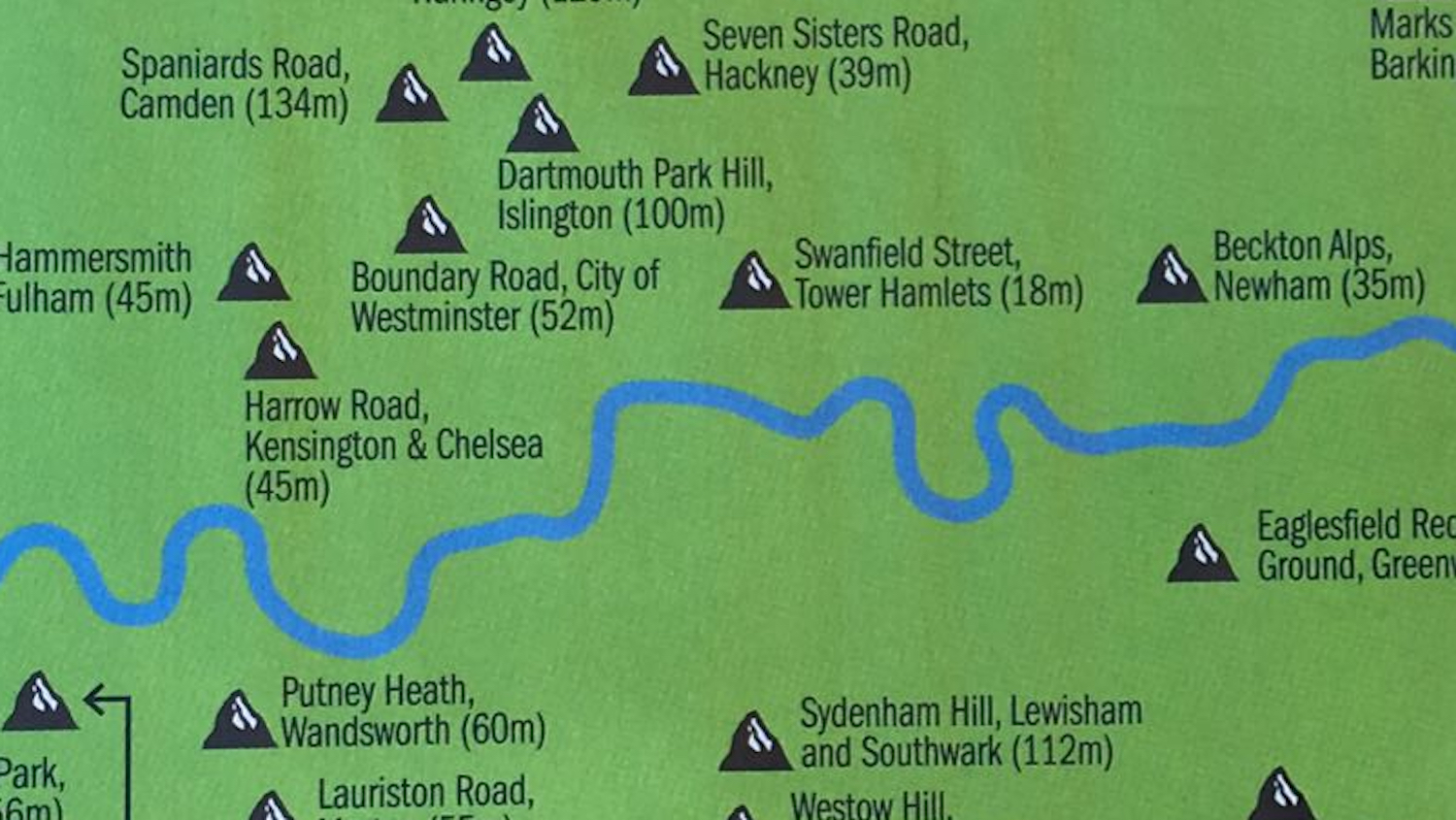

At its greatest extent, Middlesex, its southern border being the Thames, stretched from the river Lea in the east [10] to the river Colne in the west [11]. Middlesex’s only land border was to the north, and followed a ridge of hills [12], including Oxhey Hill (438 ft.), Harrow Weald Common (475 ft.), Bushey Heath (504 ft.), Deacons Hill, Edgware (478 ft.), and Highwood Hill (443 ft.).

Middlesex and its six hundreds. [Image taken here from British History Online]

Like the other 38 historic counties of England, Middlesex was divided into hundreds. In Saxon times, a hundred defined an area large enough to sustain 100 households. Until they were replaced by districts in 1894, hundreds were the only administrative unit between counties and parishes, and were the essential locus for dispensing justice, raising soldiers and discussing the affairs of the day. They were usually named after the place where the men of the area gathered to witness the dispensing of justice, the raising of armies, and the debating of matters of state.

One such place was Oswald’s Stone, the other five Middlesex Hundreds being Edmonton, Elthorne, Gore, Hounslow and Spelthorne. The City of London, nominally part of Ossulstone, became a self-governing county in the 13th century. From 1585, the City and Liberty of Westminster also attained a degree of autonomy from Middlesex.

Middlesex County Council (in green), and the territory lost at its establishment (in yellow) in 1889. [image taken here at Wikimedia]

London, and to a lesser extent Westminster, would become the names attached to the capital of England, and later of Britain, and of the urban growth that this position allowed. Middlesex was merely the canvas over which this expansion was poured – its only option to absorb the growing metropolis, and retreat from it.

In 1889, county councils were introduced in England. About 20% of the area, and 33% of the population of Middlesex – taken from Ossulstone, the most densely populated hundred – was transferred to the new County of London. Ironically, the new Middlesex County Council met in the Middlesex Guildhall, located in… the County of London [13].

London County Council (in white) and Middlesex County Council (in green), both succeeded by Greater London (thick red line) in 1965. [image taken here from the City of London homepage]

London’s expansion proved unstoppable, due to better transport links, especially the extension of the Metropolitan Tube line to the northwest of London into a rapidly suburbanising area known as Metroland. This cut right into what remained of Middlesex exceptionalism – which in the context of the expanding city meant: a rapidly rarefying ruralism. The death blow came in 1965.

Middlesex nevertheless lives on. Some even dream of a Greater Middlesex, encompassing not just the historical County of Middlesex (which preceded the much smaller Middlesex County Council), but also ‘tribal areas’ from the Chiltern Hills in the west, to “somewhere near Luton” in the north.

Putting the Great back into Middlesex: from the tiny County Council (green) to the Tribal Lands (all colours). [image taken here from the Middlesex Federation website]

“The current Government are keen to bring in regional government for England. This will almost certainly mean the abolition of all County Councils, so from Herts to Surrey everyone will end up in the same boat as Berks and Middlesex. It is possible that with the current review the regions of England will be based on the kingdoms and provinces of the Anglo-Saxons.”

Well, why not? But something tells us they’d have to find Middlesex’s ‘palladium’ first. As yet, however, the only tangible remnant of the missing monolith is Ossulston Street, leading off the Euston Road past the British Library.

So if you have an antique stone in your basement that emits a strange glow at night and low moans at full moon, let us know: it might be Oswald’s Stone, pining for Tyburn.

A modern, practical interpretation of ancient county: the catchment area of the Middlesex Association for the Blind.

Strange Maps #605

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

[1] The prehistoric names of these pathways are lost. They were renamed and upgraded by the Romans. The north-south road was labeled Iter III (Road Number Three) in the Antonine Itinerary, later called Watling Street by the Anglo-Saxons and locally known as Edgware Road (to the north of Marble Arch) and Park Lane (to the south of it). The east-west one was called Via Trinobantina, connecting Colchester with Hampshire, now better known around these parts as Oxford Street (east of the Arch) and Bayswater Road (west of it).↩

[2] Traditionally by hanging, from a gallows often called ‘the Tyburn Tree’. The prisoner(s) would be led from Newgate Prison (or the Tower, if they were nobility) through the city, enjoying a last ale at St Giles in the Fields (or, again if they were nobs, a glass of sherry at the George and Blue Boar, a now defunct pub in Holborn). The prisoners’ option of saying a few uncensored last words gave rise to Speakers’ Corner, now in the part of Hyde Park closest to Marble Arch. It is estimated that throughout the centuries, as many as 50.000 people were put to death at Tyburn. The highwayman John Austin was the last person to be executed at Tyburn. Later executions took place outside Newgate Prison. The last person to be executed in public in Britain was a Fenian bomber, Michael Barrett, in 1886, after which executions moved indoors to Newgate Prison itself. Curiously, no single person was the last person hanged in Britain; that dubious honour goes to two men, both convicted for the murder of the same man, and hanged at the same time: Peter Anthony Allen at Walton Prison in Liverpool, and Gwynne Owen Evans at Strangeways Prison in Manchester, both hanged at 8.00am on 13 August 1964. The death penalty for murder was abolished in 1965 in Great Britain (only in 1973 in Northern Ireland), and for all other offences (notably treason) in 1998. ↩

[3] The arch, in white Carrara marble and based in part on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, was designed in the 1825 as the ceremonial front gate to Buckingham Palace. Construction was completed in 1833, but the gate was considered a less than perfect addition to the Palace – soon losing much of its whiteness due to pollution by the famous (and then still quite vicious) London smog. In 1851, it was moved to its present location. The arch contains three rooms which were used as a police station from 1851 to at least 1968. Passage through the arch is limited to members of the Royal Family and the King’s Troop; in 1953, on her way to coronation, princess Elizabeth drove through the arch in the gold state coach. ↩

[4] Oswald’s Stone is not the only mysterious marker of great antiquity in London. The London Stone has been associated with King Arthur, who according to some pulled Excalibur from this rock, and/or with Brutus, the mythical founder of London. Some consider it London’s ultimate safeguard (‘So long as the Stone of Brutus is safe, so long shall London flourish’) – in other stories, the Raven of the Tower are London’s ‘palladium’ (i.e. magical protection). Other myths, of London Stone’s Roman or Druidic origin and use, abound, but the truth is that, like Oswald’s Stone, nobody knows what it stood for. But unlike Oswald’s Stone, the London Stone, although probably greatly reduced from its ancient size, has not been lost, and is still on public display. It is visible in a niche at a front of 111 Cannon Street. ↩

[5] As in: land of the Middle Saxons, between the lands of the East Saxons (i.e. Essex), South Saxons (Sussex) and West Saxons (Wessex). The latter geographic entity has also has disappeared off the map, although Thomas Hardy used a (fictionalised) version for his novels, and a regionalist movement exists with the aim of reviving Wessex as a political entity. One of their many problems: defining the boundaries of that entity. We’ll keep the question Where is Wessex for a later post, shall we? ↩

[6] Small parts were transferred to Hertfordshire (Potter’s Bar), Surrey (Staines, Sunbury-on-Thames). ↩

[7] The anniversary of the Battle of Albuera (1811) during the Peninsular Campaign, at which the Middlesex Regiment (the ‘Die-Hards’) fought valiantly against the Napoleonic Armée du Midi. The Regiment got its nickname at Albuera when their commander, severely wounded and his horse shot from under him, urged his outnumbered soldiers to “Die hard, 57th, die hard!” In a evolution typical of all things Middlesex [8], the regiment lost its name when it was amalgamated in 1966 into the Queen’s Regiment. ↩

[8] Middlesex just doesn’t seem a viable proposition, not even as a noble title. The Earldom of Middlesex was created twice, in 1622 and 1677, but died out on both occasions. ↩

[9] At least some of the area covered by the post codes beginning with EN (for Enfield), HA (Harrow and environs), TW (Twickenham and surroundings) and UB (Uxbridge &c.) ↩

[10] Flowing through the Olympic Park in Stratford and debouching in the Thames opposite the O2 Arena (formerly the Millennium Dome) in Greenwich. ↩

[11] The Colne, one of a handful of rivers so named, flows into the Thames in the marshlands that still constitute a border – these days between Greater London and Buckinghamshire. ↩

[12] A marker near the northern border, sometimes used as pars pro toto its entirety, is the Grimsdyke (or Grim’s Ditch), stretching some 2 miles from Harrow Weald to Bushey Heath. Several Grimsdykes exist throughout southern England, all earthenworks possibly thrown up as boundary markers by Celtic tribes in the last centuries BC. ↩

[13] On Parliament Square, facing Big Ben. Since 2009, Middlesex Guildhall is home to the UK’s Supreme Court. ↩