Do you prefer subs or dubs? Here’s a map for that.

Image: MapChart, reproduced with kind permission

- The boom of international content is fueling the rise of dubbing, or ‘re-voicing’ the movie or series in another language.

- As old as the ‘talkies’, dubbing and subtitling won out over a competing technique known as ‘multiple language versions’.

- As this map shows, Europe is deeply divided between subbing and dubbing – and between different kinds of dubbing.

The Woods | Official Trailer | Netflixwww.youtube.com

How do you like your foreign-language movies and series: subbed or dubbed? International content is booming on streaming services. So even for English-speaking audiences, long used to their language ruling screens both silver and small, it’s an increasingly relevant question.

And one without a definitive answer: both subtitling and dubbing (a.k.a. ‘re-voicing’) have inherent drawbacks. Watching something ‘in foreign’ means the subtitles subtract from the work’s visual integrity; but choose the version dubbed into your own lingo, and you may feel short-changed in the authenticity department.

Nevertheless, most people have a clear preference one way or the other. Like Harlan Coben, whose 2007 thriller “The Woods” was adapted into a Polish-language Netflix series – and then subbed and dubbed back into English. He recently tweeted: “Netflix gives you the choice to watch The Woods dubbed or subtitled. I urge you to use subtitles, (but) you do you. Rock on.”

Coben later replied to a fan (who said they were watching the subtitled version): “Yes. This is the best way to watch a show or movie – original language setting with your language in subtitles (but) if you want to watch with English dubbing, hey, cool, I’m not in the judging business.”

Coben’s opinion chimes with that of the ‘arthouse’ audience, which prefers to sample foreign fare in the original language with subtitles, for authenticity’s sake. They’re vocal about their preference, but recent data suggests they’re the minority. As many as 36 percent of Netflix subscribers in the U.S. watched Spanish smash hit “Money Heist” (“Casa de papel” in the original) in the dubbed version. Only a few percent watched it with subtitles.

Moreover, there is evidence that good dubs increase audience engagement, and that viewers – American ones at least – are more likely to finish the dubbed version of an episodic drama than the subbed one.

The arthouse crowd might be unable to support the loss of the near-immersive quality of subtitling, but the obvious reason for the popularity of dubbing is practical: it’s easier to use as ‘wallpaper’. Just try to do the ironing while keeping up with “The Woods” in Polish with subtitles.

STUMMFILM mit Live-MUSIK von Richard Siedhoff zu “Easy Street” von Charlie Chaplinwww.youtube.com

One major argument for subtitles – besides the ‘arthouse’ one, that is: it’s about 10 times cheaper than dubbing with a full voice cast, not to mention a lot faster. But that seems to be a consideration of the past. The aforementioned boom in international content is generating economies of scale that favor dubbing. Netflix alone works with 165 dubbing studios around the world.

The rise of dubbing is symptomatic of the internationalisation of global viewing culture, long dominated by Anglophone productions. What’s happening is in fact a re-globalisation. The silent movie ecosystem, which held sway until the late 1920s, was remarkably cosmopolitan. Re-purposing a silent movie for another language market was easy: just translate the title cards, and hey presto – another audience served. By 1927, your typical Hollywood film had its intertitles translated into as many as 36 languages.

When the ‘talkies’ came in, the movie industry stumbled headlong into something it had not yet experienced: a language barrier the size of the Tower of Babel. A spoken movie could reach only one language group. How to reach all those others? Subtitling and dubbing were used from the beginning, but for a few years in the early 1930s, it seemed a third solution would win out: multiple language versions, or MLVs.

Here’s how that went: A movie studio would hire foreign-language directors and actors to re-shoot the same film, taking turns scene by scene. In 1930, for example, William C. de Mille’s movie “The Doctor’s Secret,” originally in English, was simultaneously shot in Spanish, French, Italian, Swedish, Polish, Czech, and Hungarian as well.

Laurel et Hardy sonorisés en français dans un homme à la barre (parlant)www.youtube.com

Some stars were too famous to be replaced, and had to re-shoot the MLVs themselves, learning their lines in another language. Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy’s own French-language efforts became so familiar to audiences in France, that when they were eventually replaced with French voice-over artists, these had to keep the American accents of the original actors.

MLVs were cumbersome and costly, and by the mid-1930s, they had turned out to be an evolutionary dead end. Dubbing and subtitling started to take over and the industry never looked back. MLVs were occasionally revived though, even as late as 1979, when Werner Herzog shot German and English versions of the same vampire movie, using the same cast: “Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht” and “Nosferatu the Vampyre,” respectively.

In a world dominated by Hollywood, dubbing established itself as the preferred translation method in France, Italy, Germany and Spain. These are Europe’s four biggest non-English-speaking markets, so dubbing – more labor-intensive and up to 10 times more expensive than subbing – made more economic sense there than in smaller markets.

Subtitling became the go-to solution for most of those smaller markets: Scandinavia, the Netherlands, Portugal, the Balkans.

Yet some other smaller markets, the Czech and Hungarian ones to name two, also preferred dubbing. That’s because economy wasn’t the only factor. Cultural pride also played a part. France had always considered its culture and language a bit above the vulgar English tongue, for example. Another factor: politics. Dubbing was an attractive way to censor foreign imports, especially for the fascist regimes in Germany, Italy, and Spain.

The Terminator – Oneliners GERMANwww.youtube.com

Once set, national preferences remained fairly stable after World War II, when the import of mainly English-language movies boomed across Western Europe. Today, Italy even has the Gran Premio Internazionale del Doppiagio, an annual Oscars-like ceremony for excellence in dubbing.

In bigger dubbing markets like Germany, voice actors became celebrities in their own right. Recently-retired German voice actor Thomas Danneberg dubbed around 1,500 movies into German, including Arnold Schwarzenegger’s entire oeuvre (whose Austrian accent would have disqualified him from doing his own dubbing in High German).

Mr. Danneberg dubbed a great number of actors, which could be an issue when several appeared in the same movie. When Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone appeared together in “The Expendables” (2010), Danneberg made sure to say the lines of both at a slightly different pitch.

In Eastern Europe, meanwhile, another alternative gained prominence, called voice-over translation (VOT). Unlike with dubbing, where the original soundtrack is replaced, VOT adds the translated dialogue over the original, which remains audible. It’s a technique familiar to Western audiences from documentaries or news reports, not for fiction.

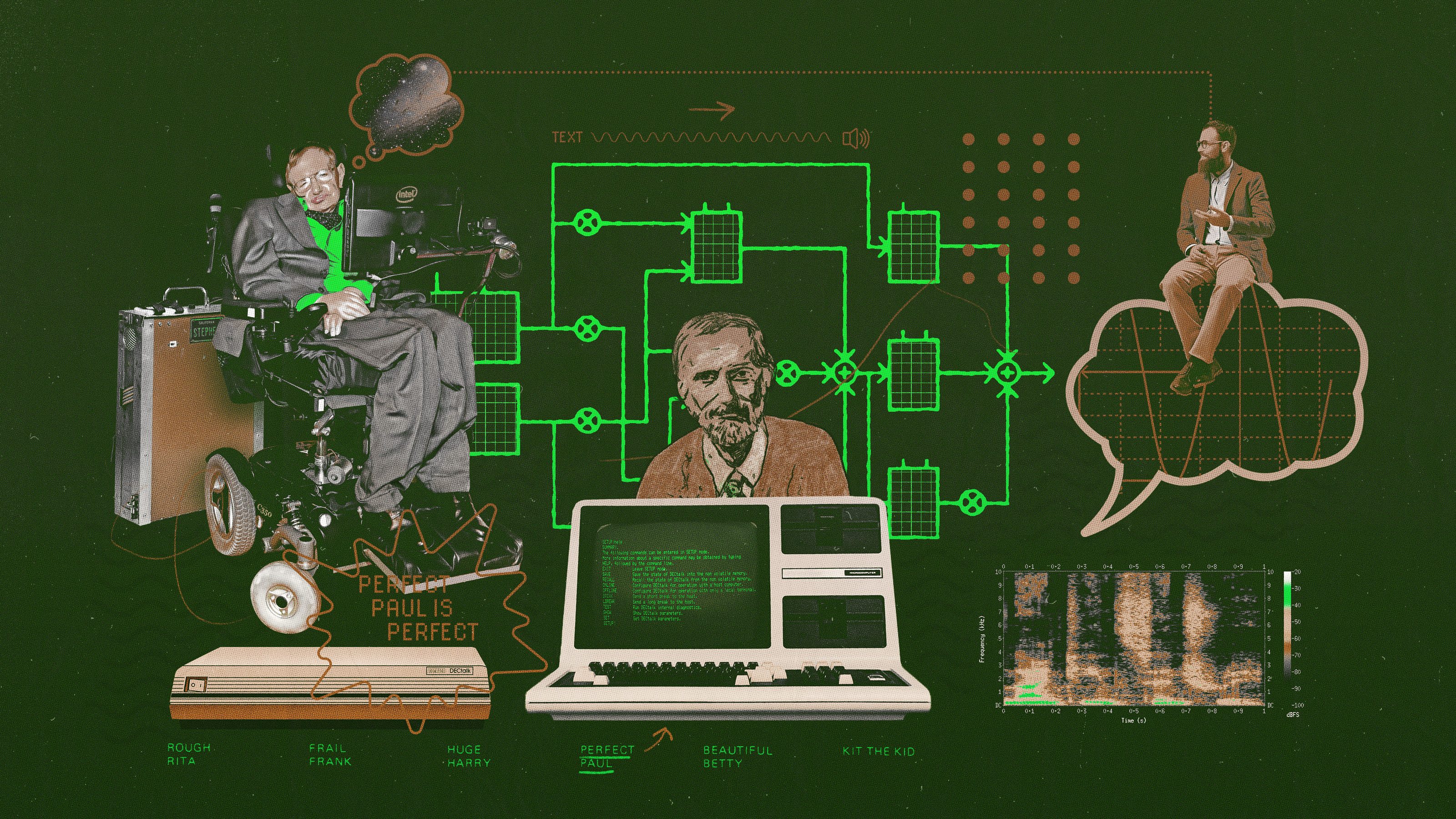

In red: dubbing markets. Dark blue: subtitles, please. Yellow: voice-over translation. In green: markets using dubs from another language (i.e. Czech for Slovakia, Russian for Belarus). Light blue: Belgium, where the Dutch-speaking north prefers subbing, the French-speaking south subbing.Image: MapChart, reproduced with kind permission

In Polish and Russian, ‘lektors’ are a cheap and culturally accepted way to translate foreign movies. In Russia, these are known as Gavrilov translations, after one of the three most prolific voice artists doing these single-voice translations. Each had their specialty. While Andrey Gavrilov went for action movies, Aleksey Mikhalyov gravitated towards comedy and drama, and Leonid Volodarsky is best remembered for his dubbing of “Star Wars.” The tradition is continued by a new generation of Gavrllov translators.

But for how long? Because dubbing is improving at a terrific speed. In the near future, the technology behind ‘deep fakes’ will help produce dubs that perfectly synchronise the ‘flaps’ (dub-speak for mouth movements) with the words voiced over, while ‘voice cloning’ will be used to adjust the voice of the re-recording artist to that of the original actor.

It may convince the Eastern European markets to abandon VOT – which is the poor cousin of dubbing anyway. But it’s less certain that it will dislodge subbing from markets where it’s become ingrained, and frequently mentioned as a reason for relatively high levels of English proficiency. So it may be a while yet before the Terminator says “I’ll be back” in Swedish.

Strange Maps #1035

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.