What did Europeans actually discover? Not all that much

- Columbus’ reputation is not the only one up for revision. The entire Age of Discovery was not all it is cracked up to be.

- This map shows what Europeans actually discovered: a few out of the way islands and some frozen wastes.

- Is this map taking historical revisionism a step too far, or is it an antithesis looking for a synthesis?

Historical revisionism has had a bad reputation ever since Orwell savagely satirized it in 1984 and Stalin savagely practiced it in the Soviet Union. But perhaps we need to revisit our reservations about revisionism.

There’s nothing wrong with using new evidence or insights to reinterpret the historical record — as long as the new version is up for scrutiny, too. Tie a cravat around my neck and call me an old-fashioned Hegelian, but when a thesis meets its antithesis the result should be a better synthesis.

Case in point: the Age of Discovery. The prevalent and Eurocentric view has long held that Europeans discovered most of the world. But today, it’s pretty hard to find anyone who wants to touch that particular thesis with a 10-foot pole.

Take Columbus, for example. Once hailed as the discoverer of America, the world’s most famous Genoan is now rather infamous, being pushed off his pedestal everywhere — figuratively, if not literally. You want reasons? The pedestal shakers have plenty:

- Columbus’ voyages inaugurated an era of unprecedented genocide, exploitation, and devastation in the Americas, perpetrated by various European powers.

- Columbus wasn’t even the first European to discover the Americas; the Vikings got there earlier.

- Neither of them actually discovered the Americas. That honor should rightly go to the continent’s indigenous First Peoples.

You can make similar arguments about other places that were supposedly “discovered” by Europeans, such as sub-Saharan Africa, Polynesia, and Australia. (Minus the Viking argument; they never made it to any of those places, at least not as far as we now know.)

So, where does that leave us? It leaves us with this map, which deconstructs the “classic” view on the Age of Discovery by subtracting from the list of European conquests all those lands previously inhabited or discovered by other peoples.

The resulting roll call of European discovery is still pretty global but a lot less substantial, both in terms of area and current population. All that remains is a bunch of diminutive islands sprinkled across the various oceans. The only significant land masses first sighted by Europeans are the inhospitable interior of Greenland and the equally uninviting frozen tundra of the Antarctic.

The map legend lists the discovering countries in chronological order, from Portugal making Europe’s first discoveries in 1418 (Porto Santo, north of Madeira) to Norway, discovering Lonely Island in 1878.

Portugal

The Portuguese discovered a string of previously unknown islands in the Atlantic, all the way from Sable Island off Canada (see also Strange Maps #387) to Gough Island, even farther south than Tristan da Cunha. They were also the first visitors on a lot of islands in the western part of the Indian Ocean, mainly around Madagascar, from the Seychelles in the north to Réunion in the south.

Spain

Saint Paul Island is a Portuguese discovery farther south. Nearby Amsterdam Island was first sighted by Portugal’s arch rivals, the Spanish. Spain’s own discoveries are concentrated around the Americas, with Bermuda and the Cayman Islands in the Caribbean, and a long swath of islands from Guadalupe to the Galapagos to the Juan Fernandez Islands along America’s Pacific coast. A bit out of the way are the Bonin Islands and a few other currently uninhabited islands, all in the North Pacific. These were discovered by Spanish explorers looking for an easy commute between the Philippines and Mexico, when both were Spanish colonies.

Netherlands

The Dutch only made a handful of first discoveries. The claim that Sebald de Weert, a Flemish captain in Dutch service, was the first European to sight the Falklands is disputed by English and Spanish sources. Less contested are the first sightings and visits by Dutch sailors on Jan Mayen and Spitsbergen (a.k.a. Svalbard).

Great Britain

The British’s discoveries are limited mainly to the southern hemisphere, including many islands near the Antarctic, such as South Georgia and the Heard & McDonald Islands, as well as some near-Australian (and near-New Zealand) ones, from Cocos and Christmas via Lord Howe and Norfolk to Bounty and Antipodes Island.

France

French sailors discovered a threesome of cold and lonely South Indian islands (Bouvet, Crozet and Kerguélen; see Strange Maps #519), Tromelin (somewhat warmer, but with a gruesome history), and Clipperton in the Pacific. All are currently uninhabited, except for the scientific crews that get to experience the world-beating desolation and isolation of these islands firsthand.

Russia

Russia’s discoveries are limited to its own extremities: the very north of Siberia and some islands towards the North Pole, as well as a few dots of land in the North Pacific.

United States

The United States discovered a handful of Pacific islands, including Johnston Atoll (now basically a giant airstrip in the middle of the ocean) and Wrangell Island, north of Siberia. In 1881, an American ship landed on the island and named it “New Columbia,” claiming it for the U.S. (The proclamation didn’t stick.)

Austria-Hungary

Improbably, even the sedate, land-based, and now-defunct Austro-Hungarian empire made some overseas discoveries, naming an Arctic archipelago after their emperor, Franz Josef. Now Russian, the islands harbor the country’s northernmost military base, at Nagurskoye.

Norway

Norway discovered a few Arctic islands, including one they called Ensomheden (Lonely Island), now the Russian island of Uyedineniya, which means the same. In 1942, a German U-boat destroyed a Soviet weather station on the island, which looks like it will be the island’s one and only footnote in history.

Polar areas

Brits and Norwegians both claim discovery of the frozen ends of the world, with the Russians also throwing their hat into the ring for the Antarctic.

So, what do Europe’s genuine discoveries add up to? Leaving the frozen wastelands of Antarctica and Greenland out of the equation, all the islands on the map put together bulk out to just 213,342 km2 (82,372 sq. mi).

Size-wise, the country that comes closest to that figure is the United Kingdom (241,930 km2, 93,410 sq. mi) — or, if you prefer a U.S. state, Utah (213,100 km2, 82,278 sq. mi). Think what you will about either of those places: As a territorial summary of centuries’ worth of discovery, they don’t amount to much.

In terms of population, the tally is even less impressive: Just more than 3.5 million people live in those “discovered” territories, or barely 5 percent of 1 percent of the global population.

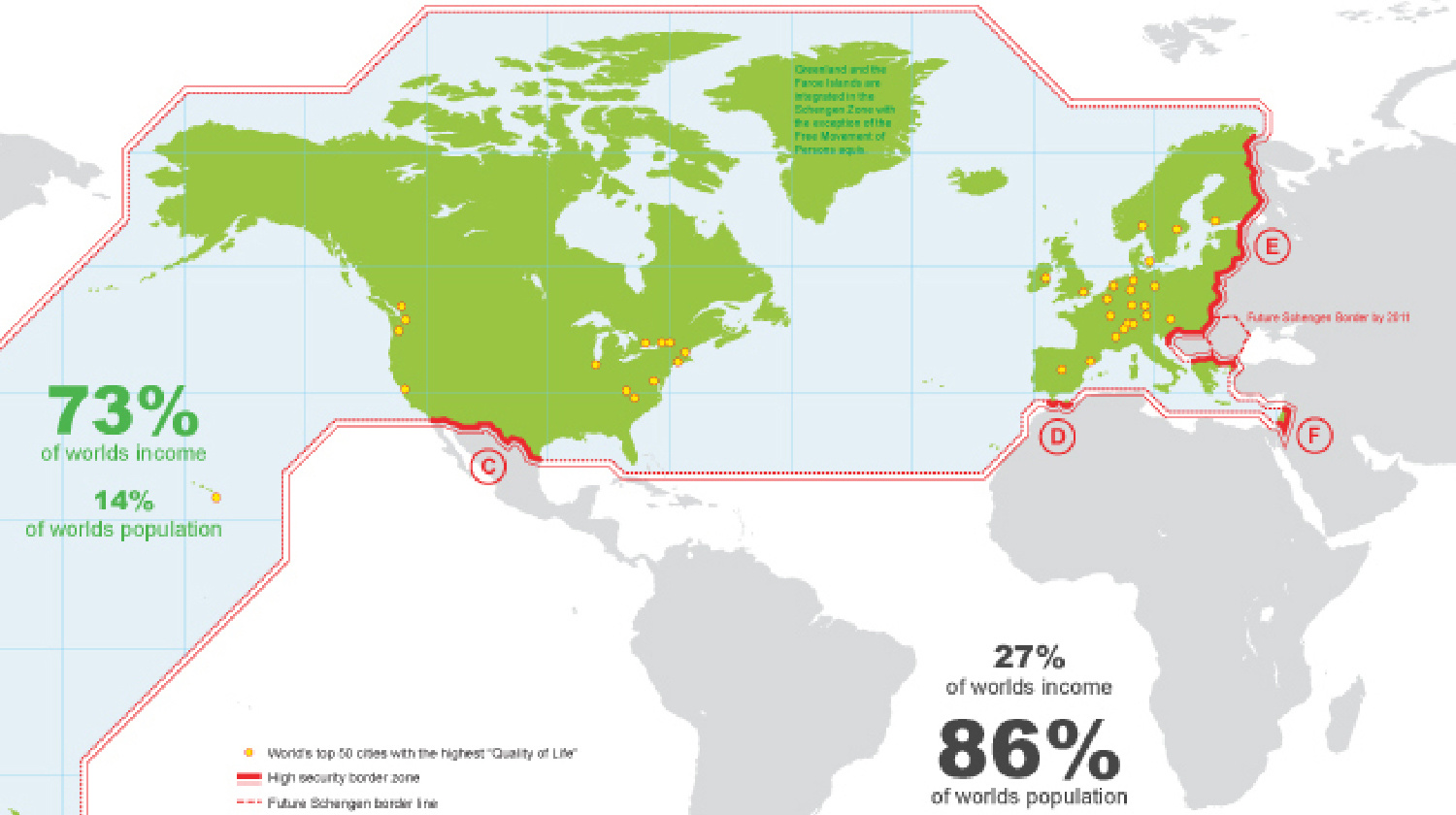

Those figures seem to suggest that the Age of Discovery was of little consequence, and that Europe’s impact on the wider world was insignificant. As an antithesis to the previous Eurocentric consensus, this corrective map is worth examining. But it misses a larger point.

Let’s return to Columbus. For all his faults (and they were many), his nondiscovery of America did represent the moment when the Old World (i.e. the “world island” consisting of Europe, Africa, and Asia) was definitively introduced to the new one, and vice versa.

More generally, the actual point of discovery is not who got there first, but rather who got there last — in other words, the person who definitively brought said island, territory, or region into the orbit of global commerce and communication.

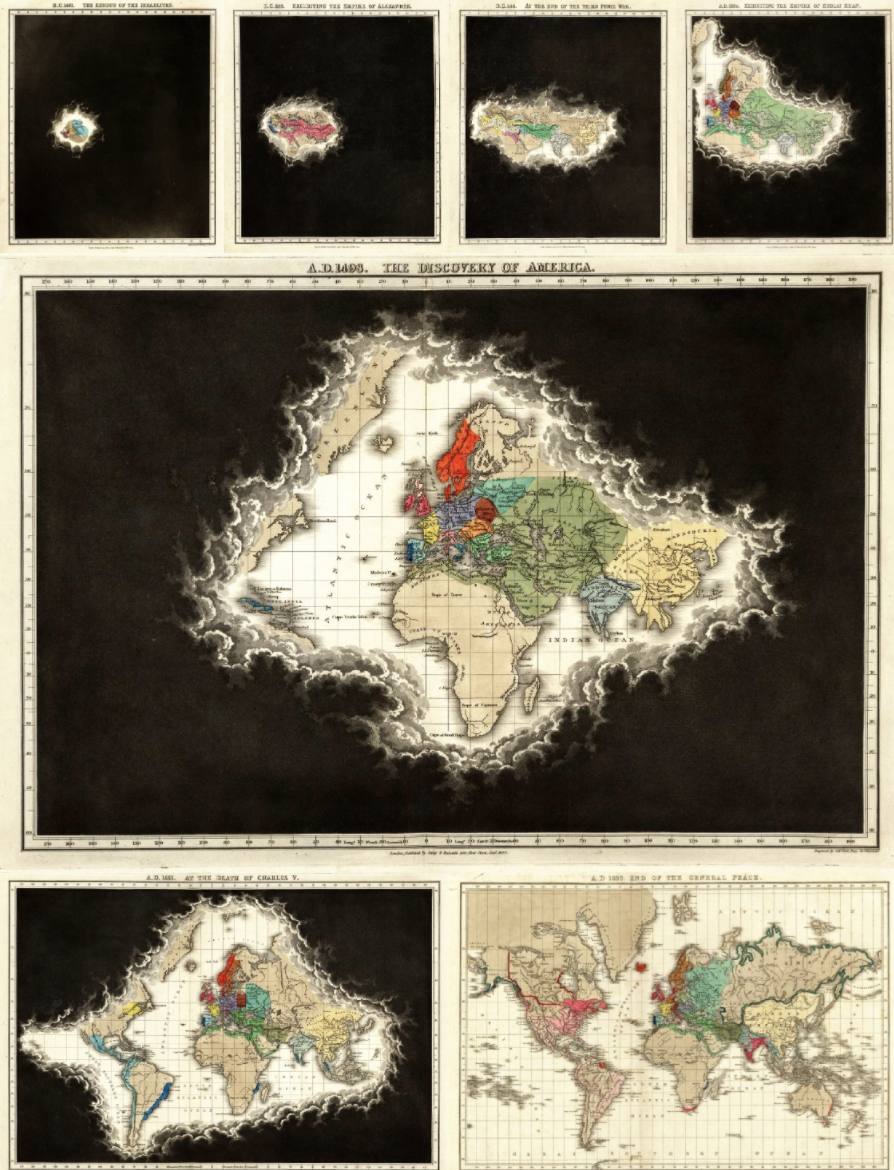

For many centuries, western Europe was at the nexus of that process. But there is nothing inherently western European about globalization. Both points are (inadvertently) made by the famous map series in Edward Quin’s Historical Atlas (1830) that shows the growth of the known world by the shrinkage over time of the “clouds of unknowing.”

Of course, known and unknown are relative, and they’re seen from the perspective of the author — in this case, from a 19th-century, British, and Christian point of view. Still, the world started globalizing long before that, and the process was perpetuated by peoples and empires who were not necessarily on friendly terms with each other: Romans and Hebrews, Franks, and Mongols.

For much of history, the “known world” stretched from northwestern Europe to southeast Asia. Columbus’ accidental (re)discovery of the Americas was the catalyst that eventually evaporated the clouds of unknowing across the entire world.

By some accounts, the last major territory to be discovered was Severnaya Zemlya (“Northern Land”), which was yet another Siberian archipelago, first spotted in 1913 and not explored until roughly 1930. So, we’ve filled in all the blanks on the map. Discovery — with or without quotation marks — is over, and Europe’s contribution to it — with or without quotation marks — is history. However, globalization continues, and its center of gravity has long since moved away from the Old Continent. And that might be the actual point of the map above.

“Actual European Discoveries” map found here at Bill Rankin’s amazing Radical Cartography page. The maps showing the shrinking clouds of unknowing are part of Edward Quin’s longer series, shown and discussed here at the Public Domain Review.

Strange Maps #1110

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.