Mapping Middle-earth: The lopsided demographics of Tolkien’s universe

- Lots of weird and wonderful creatures populate Middle-earth, but not a single census taker.

- Don’t worry: Somebody took that job upon themselves and drew up the requisite stats and graphs.

- Demographic analysis reveals just how gender-imbalanced Tolkien’s world is (and more).

Wizards and Trolls, Elves and Hobbits, not to mention the occasional Ent or Ringwraith…Middle-earth teems with the strangest creatures. What the place lacks, unfortunately, is the one life form that can make statistical sense of it all: a census taker. Fortunately, there’s no need to imagine a bureaucrat armed with a clipboard stalking the streets of Bree or quantifying the goings-on in Fangorn Forest. Someone’s leafed through all the pages of Tolkien’s legendarium and decanted its rich pageant into a government-issue spreadsheet.

Bureaucrats stalking the streets of Bree

That someone is Emil Johanssen, a Swedish chemical engineer fascinated by “data visualization and the wonderful world created by J.R.R. Tolkien.” There are maps as well in his LOTR Project (and we’ll get to those). But first: a taste of the demography of Middle-earth, based on an analysis of the 982 characters that populate The Hobbit, the Lord of the Rings trilogy, The Silmarillion, and other posthumously published works.

What follows is the bewildering collision of fantasy and statistics: a rigorous inventory of a world intentionally left blurred around the edges. For a more detailed analysis, check the LOTR Project itself. For now, here are several big takeaways.

Gender balance

Or rather, lack thereof. As even the most cursory reader will have noticed, Middle-earth is quite the sausagefest. The action is driven by males (albeit of various sizes and races), and females are few and far between, and almost invariably in a supporting role.

The stats bear this out: 82% of Tolkien’s characters are male. Hobbits come closest to parity, with 30% women, followed by Men (which is what Tolkien called the human race in his books), where the imbalance is 87% versus 13%.

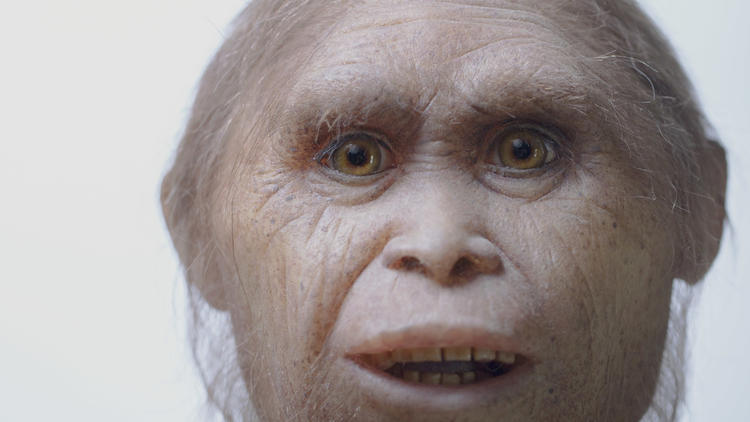

Females are rarer still among Elves, and are not attested among Orcs, at least not in the canon. That doesn’t mean Tolkien didn’t give the matter any thought. In a letter from 1963, he wrote to an inquiring fan that “there must have been Orc women.”

Yet he was of more than one mind: In the posthumously published story The Fall of Gondolin, the Orcs were created by sorcery out of slime. Other theories expressed across Tolkien’s works suggest that Orcs are fallen Elves or the offspring of unions between Elves and beasts.

Dís is the only female Dwarf named by Tolkien, and even then only in a genealogy that honors the deaths in the Battle of the Five Armies of her two sons, Fíli and Kíli. Sprinkled throughout Tolkien’s work are indications of why Dwarf-women are so invisible: Only about one-third of Dwarves are women; they keep to themselves inside their subterranean halls, and when they do travel abroad, they disguise themselves as Dwarf-men (which is not particularly difficult, considering, according to one source, they have beards). Because the other races saw so few Dwarf-women, legend had it that Dwarves were born of stones.

Life span

Based on characters with known birth and death dates, we can conclude that the average Hobbit lived to 96.8 years — almost half the average Dwarf life span of 195 years. Dwalin, the second-oldest Dwarf we know of, reached his 340th birthday, and others also made it past 250. Dwarves’ comparatively low average longevity is due to their high casualty numbers in battle.

The life expectancy of Men is all over the place: from 58 years in the First Age to 330 years in the Second Age, and back down to 145 years in the Third Age. Why the wild variation? It turns out the answer has less to do with Age than origin: Men of Númenorean blood have an average life span of 237 years, while the ordinary Men of Middle-earth expire just before their 82nd birthday — still slightly better than the average U.S. life expectancy (77.5 years in 2022).

Oldest and youngest

Even more interesting than the averages are the extremes. The oldest of the Men mentioned by Tolkien is Elros, who lived to be 500. But that is cheating a bit because he was a half-Elf (like his brother, Elrond). Otherwise, the oldest Men are all rulers of Númenor: Tar-Atanamir, the 13th King (421 years); Tar-Ancalimë, the first Queen (412 years); Tar-Amandil, the third King; and Tar-Telperiën, the second Queen (both 411 years).

Tolkien’s works slant heavily toward the older demographic, which makes us even more curious to find out who the youngest characters are in his books. The absolute youngest — of Men or any race — throughout the works is Urwen, nicknamed Lalaith (“laughter”). She was the daughter of Húrin, one of the heroes of the First Age. She died of the Evil Breath when she was just three years old.

The absolute oldest, on the other hand, is Durin the Deathless. Although this primeval Dwarf King eventually died, it isn’t hard to see how he acquired his nickname toward the end of his 2,395-year life. (Did that extraordinarily long lifespan exclude him from the calculation of average Dwarf longevity? Mr. Johanssen does not specify).

The youngest Dwarf mentioned by Tolkien is Frór, who died at the tender age of 37, killed along with his father by a giant cold-drake (a non-fire-breathing dragon) outside their hall.

The two oldest Hobbits are among the most familiar characters across the sagas. The second-oldest is Bilbo Baggins, who celebrated his 131st birthday before sailing for the Western Lands, where he died. The oldest is Sméagol — otherwise known as Gollum — who lived to be 589 years old. Both he and Bilbo had their lifespans unnaturally stretched by the One Ring, whose successive bearers they were. And while the centuries-long process consumed Gollum’s mind and body, he was originally a Hobbit too.

To say, as many do, that Bilbo had bested the record of Gerontius Took (130 years) to become the longest-living Hobbit ever is to take away the one achievement, however inadvertent, that Sméagol can rightfully claim.

The youngest Hobbit in the books is an odious fellow by the name of Lotho Sackville-Baggins. While Frodo and Sam are away on their quest, Lotho (nicknamed “Little Pimple”) establishes a totalitarian regime in the Shire with the long-distance help of Saruman.

Age of Gandalf: n/a

As the Third Age closes, Sauron is defeated, Saruman’s power crumbles, and Lotho is stabbed to death and — get this — eaten by Gríma Wormtongue at the age of 55, still a tender age for a Hobbit (or so one hopes).

To the annoyance of any serious census taker, the information that can be gleaned from the pages of Tolkien’s work remains largely anecdotal and incomplete. Gandalf, for example, is probably older than Durin, but his exact age is never divulged. Even more frustratingly, we never get a clear insight into total population figures for Hobbits, Men, or any of the other races. We just get a sense that some are dwindling fast. So, Kudos to Mr. Johanssen for wringing as much statistical sense out of the sagas as he could.

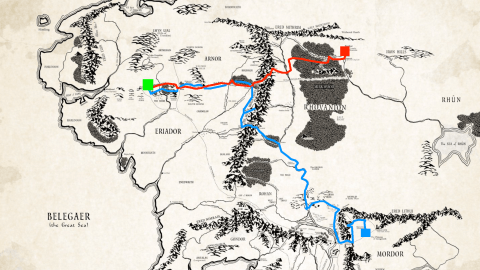

There’s one other thing that his LOTR Project — seemingly on hiatus since mid-2015 — does well: maps. With the same obsession for detail, it sketches out the various voyages undertaken by Bilbo, Frodo, Gandalf (in his Grey and White guises, separately), and others, allowing you to see where they overlap and diverge.

You can toggle the map of Middle-earth to become the map of Beleriand (which was part of Middle-earth at an earlier age). These quests and places are less familiar to the “Ringers” (i.e. those Tolkien fans who stick to the more accessible parts of his oeuvre: The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings).

Similarities and differences between Bilbo and Frodo’s trips

Staying in the Third Age, you can combine the tracks across the landscape with a register of places, showing the named settlements, mountains, bodies of water, and regions of Middle-earth, each linked to an entry in the Tolkien Gateway. (Did you know that Dol Guldur (“Hill of Sorcery”) in southern Mirkwood, long a stronghold of Sauron, once had been Amon Lanc (“Bald Hill”), the capital of the Silvan Elves?)

Isolating and comparing Bilbo’s adventure with Frodo’s quest, one is struck by the similarities more than the differences: Both leave Hobbiton on a trek east all the way to Rivendell, where their paths diverge. Bilbo’s path continues east while Frodo’s much longer one heads southeast. However, both go on to successfully meet their destiny in high places (the Lonely Mountain in Bilbo’s case; Mount Doom in Frodo’s), before returning home to the Shire.

Only now — and after several re-readings — does another parallel strike me: The first chapter of The Hobbit is called “An Unexpected Party” while The Lord of the Rings opens with…”A Long-Expected Party.” Some things are so obvious as to become almost invisible — until a good map comes along to open our eyes.

Strange Maps #1228

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

Follow Strange Maps on X and Facebook.