Dogs take shortcuts based on Earth’s magnetic fields

Image source: BIGANDT.COM/Shutterstock

- As dogs navigate, they appear to be using the Earth’s magnetic fields.

- 170 dogs orient themselves to north and south as they plot shortcuts back to their people.

- Dogs join the growing number of magnetism-sensitive animals.

Dogs And Magnetic Fields

It’s been known for a while that some animals — migratory birds, mole rats, and lobsters among them — use the Earth’s magnetic fields to navigate. There’s even some evidence suggesting we do, too. In 2013, zoologist Hynek Burda found that dogs tend to poop and pee along a north-south axis, although at least some dogs (including our own Lulu) don’t agree. New research indicates that dogs also orient themselves to the Earth’s magnetic field as they invent shortcuts to get from place to place.

The research comes from Kateřina Benediktová of the Czech University of Life Sciences Prague — Burda is her PhD adviser — and is published in eLife.

Image source: Benediktová, et al

That dogs have excellent navigational talents is nothing new. The study recalls “messenger dogs” that were relied on during World War I to ferry sensitive communiqués back and forth across battle lines. In addition, of course, hunting dogs, or “scent hounds,” have long exhibited the ability to return to their owners’ positions, and previous studies have shown that they often devise new return routes, as opposed to simply retracing their steps. How they do this has been a bit mysterious, as the study notes: “Dogs often homed using novel routes and/or shortcuts, ruling out route reversal strategies, and making olfactory tracking and visual piloting unlikely.”

In trying to figure out how dogs do what they do, researchers have divided their methods into three possible modes:

- tracking — following their own scent trail back to their point of origin

- scouting — searching for a new, shorter way back to their point of origin

- visual piloting — using landmarks to find their way back

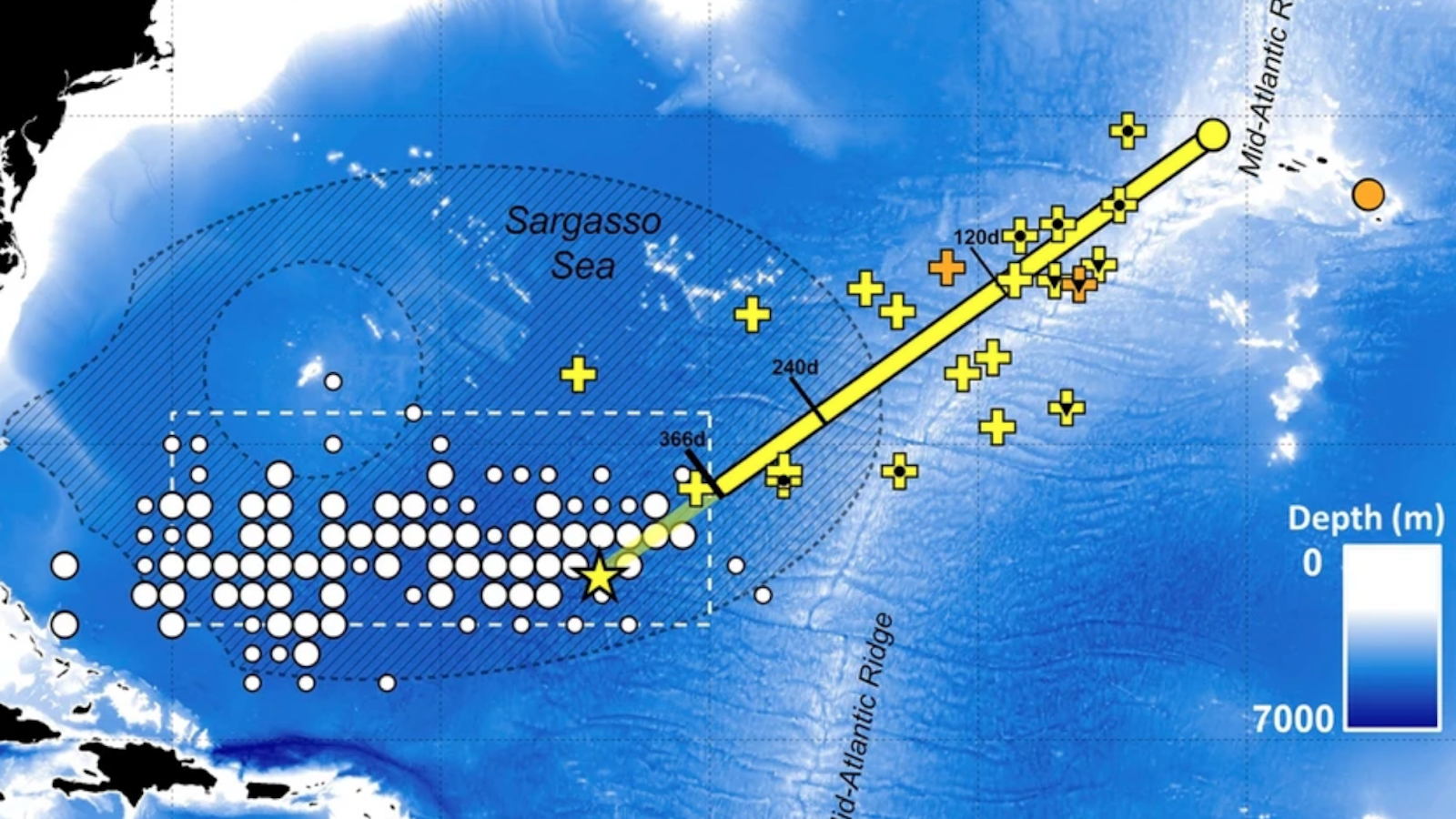

Benediktová’s research began when she put video cameras and GPS trackers on four dogs, took them out into the forest, and set them loose. As might be expected, they took off in pursuit of some interesting scent. All of the dogs eventually returned. She mapped the collected GPS data, seeing runs of both tracking and scouting.

However, when she showed her maps to Burda, he noticed something else. Just before scouting their way back, the dogs did something odd: They ran for roughly 20 meters along a precise north-south axis, as if orienting themselves, before returning to Benediktová. Without some form of magnetic sensitivity, this would not be possible.

Dogs And Magnetic Fields

A sample of four dogs is hardly definitive, so student and advisor developed a larger study involving 27 dogs who were taken on several hundred scouting trips over the course of three years. The dogs were typically taken to locales with which they had no familiarity, and the researchers avoided tipping off the canines with any navigational clues including the avoidance of situations in which wind could carry their scent toward the dogs. The researchers also hid after releasing their charges to make sure they weren’t visible to the pooches.

In the end, the researchers documented 223 scouting runs in which the dogs averaged a return to their points of origin of about 1.1 kilometers (around 0.7 miles).

In 170 of these runs, the dogs did indeed repeat the smaller sample’s behavior, running about 20 meters along a north-south axis. Just as intriguingly, it was these dogs who found the fastest, most direct route back. “I’m really quite impressed with the data,” biologist Catherine Lohmann of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, who was not involved in the study, tells Science.

Burda considers the dogs’ seeming reliance on their north-south jog to be pretty convincing: “It’s the most plausible explanation.”

Commenting on the research, dog behaviorist Adam Miklósi at Eötvös Loránd University tells Science, “The problem is that in order to 100% prove the magnetic sense, or any sense, you have to exclude all the others.”

Given the difficulties of doing that, Benediktová and Burda intend to test their hypothesis from the other direction, seeing if they can confuse dogs’ magnetnoreception by placing magnets on their collars and repeating the tests — if they no longer do their little north-south jog, a reliance on the Earth’s magnetic field would look even more likely.