Can money buy happiness? Depends on how you spend it.

- One well-known study has suggested that $75,000 annual income is the cut-off point at which money no longer makes people happier.

- But further research has shown that more money correlates with more happiness.

- One potential reason for this difference is that people who earn more spend their money differently.

Happiness is a loving family, a good meal, and an annual salary of $75,000. At least, that’s been the popular wisdom since Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton published their 2010 study looking at money’s relationship to well-being. The two psychologists reportedly found that people’s happiness increases until their annual income reaches $75,000, at which point it plateaus.

Like the Milgram experiments, the Stanford prison experiments, and the marshmallow test before it, Kahneman and Deaton’s study is one of few to explode into the mainstream. It has been cited in books, on TV shows, and across social media. CEOs set employee wages to match the findings. And smirking aunts everywhere dragged out the figure to prove that “See, money doesn’t buy you happiness.”

The appeal is easy to see. The study provided a simple solution to a knotty life problem and, to people making less than $75,000, offered an off-the-rack goal to strive for. And if we’re being honest, there was more than a little classist schadenfreude at having confirmation that Bill Gates and Elon Musk were, if not as miserable, then at least no happier than the rest of us.

But like those other experiments, the popular perception of the research is wrong. Can money buy happiness? No, your aunt is right about that one. But it can facilitate happiness if you spend it thoughtfully.

The root of all elation

Happiness isn’t just a simple binary state — a mental switch that’s flipped on when your bank account hits some magical number. It’s a complex emotion influenced by many interrelated factors. These include your work, health, relationships, schedule, stressors, education, personality, life philosophy, and on and on.

Since some of these factors can change daily, researchers often inquire about two types of happiness. The first is experienced well-being (how are you feeling in the moment or lately), and the second is life satisfaction (how you feel your life is going in general). The reason is that some participants will undoubtedly be having better or worse weeks than usual when the researchers survey them. Considering both provides a better idea of each participant’s overall happiness.

Last year, Matthew Killingsworth, a senior psychology fellow at the University of Pennsylvania, followed up on the Kahneman-Deaton study. He developed a smartphone app that would randomly ping participants to ask them questions about their experienced happiness and their life satisfaction. All told, he gathered an extensive data set, drawing on roughly 1.7 million experience-sampling reports from more than 33,000 Americans (ages 18-65).

After controlling for variables such as age, gender, and education, Killingsworth found that larger incomes were “robustly associated” with greater experienced well-being and life satisfaction — up to $80,000 and above. His data showed no obvious plateau at which point money stopped mattering. Happiness rose alongside income all the way up.

While the study didn’t look for causation, Killingsworth posited that a sense of control is an important component. Responses to the survey question “To what extent do you feel in control of your life?” accounted for 74% of the association between income and experienced well-being.

“When you have money, you have options, and that can manifest in different ways,” Killingsworth told CNBC. “Do you buy organic raspberries at the grocery store? Can you quit the job you don’t enjoy, or do you hang on because you can’t afford to be unemployed? … Do you end a relationship with someone that you’re financially entangled with?”

Setting the financial record straight

Confession time: I haven’t been fair to Kahneman and Deaton. So far, I’ve only given you the Spark Notes version of their research as shared on social media and across popular culture. But their study also looked at both experienced well-being and life satisfaction, and as you’ve probably guessed, income did not affect those in the same way.

While their study did find that experienced well-being plateaued at $75,000, it showed no such tapering off for life satisfaction. Mirroring Killingsworth’s data, it kept rising alongside income. Kahneman and Deaton reasoned that this was likely due to money only having so much influence on how people experience their day-to-day lives.

If you’re secure, healthy, live in a good neighborhood, and enjoy an active social life, then the figure in your checkbook doesn’t weigh as much on your daily happiness. You’ll have your life struggles and your bad days, but financial stress doesn’t complicate those struggles as intensely and offers a way to build resilience to them.

Conversely, if you’re struggling, unhealthy, lonely, or living in a disruptive neighborhood, then your financial straits will likely exacerbate those challenges. Indeed, they are the cause of some of those struggles. In other words, your income stops being a limiting factor in your daily happiness once it allows you to subsist and live comfortably.

Throughout a lifetime, however, your income adds up. It sets your socioeconomic status (another predictor of happiness). It opens you to opportunities that you might otherwise pass up, such as living abroad or quitting a job you despise. And it buttresses the many other factors that correlate with happiness (such as education, marital status, and emotional regulation).

The pursuit of happiness

Why the difference between the two studies? Killingsworth speculates it has to do with methodology.

Kahneman and Deaton’s data came from the Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index. It evaluated people’s experienced well-being by asking them about their emotional experiences yesterday. Questions like: “Did you smile a lot yesterday?” or “Did you experience stress yesterday?” Meanwhile, Killingsworth’s app-based approach could ask people how they were feeling in real time. This helped reduce the biases of recalled states of mind.

“People’s memories are imperfect,” Killingsworth told CNBC. “One of the advantages by design of this study is I’m getting as close as possible to pure measurement, which is, ‘How do you feel right now?’ People can answer that pretty easily, whereas if you say, ‘How did you feel yesterday? How did you feel over the last month?’ people have a much more complex mental calculation.”

Life satisfaction, on the other hand, may have been steadier because a participant’s interpretation of their lives isn’t as swayed by daily vagaries.

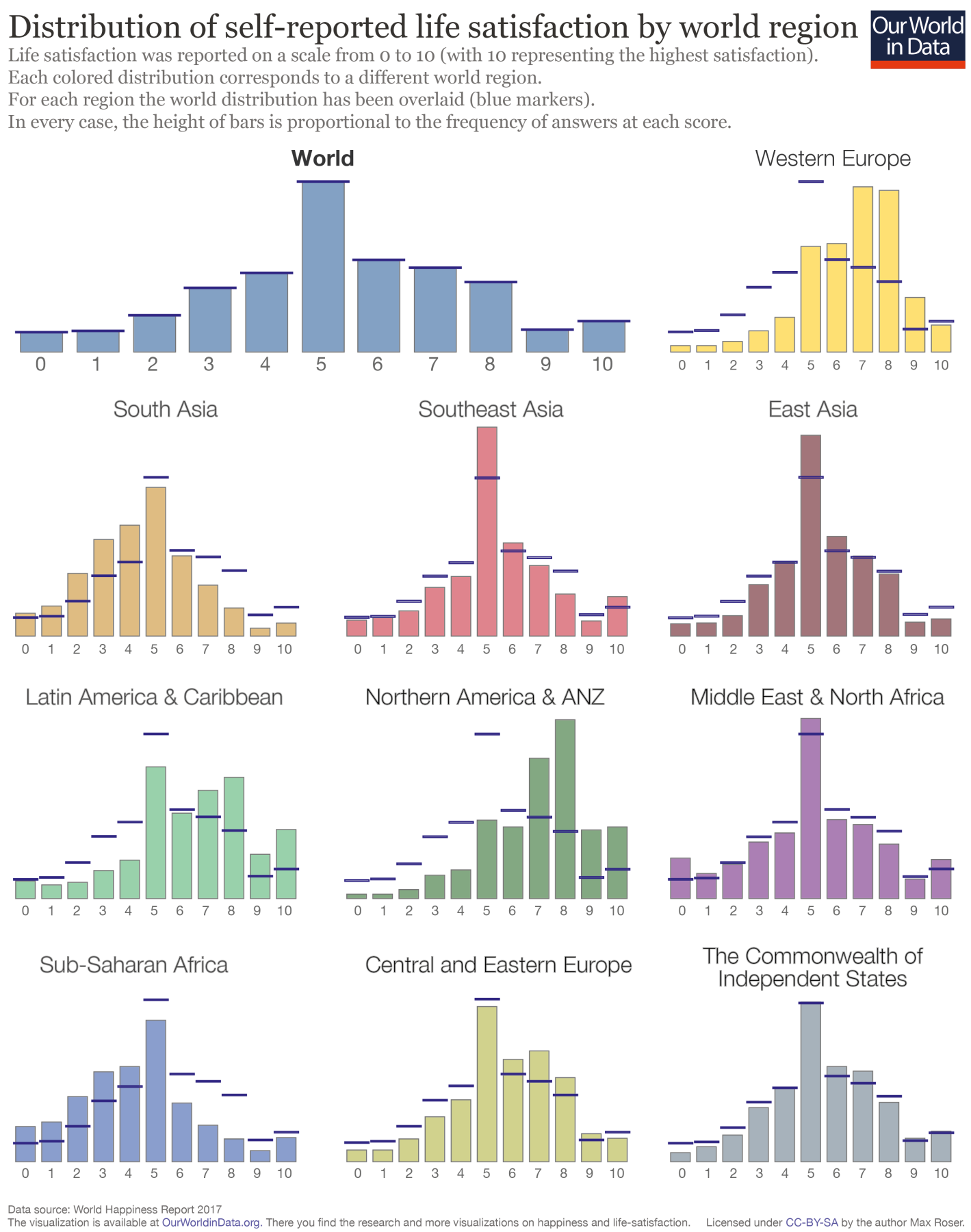

It’s also worth noting that both studies corroborate with other research that looks at the relationship between happiness and money. The World Happiness Report, for example, compares happiness surveys from more than 160 countries, with an average sample size of about 1,000 per country. While the happiest countries aren’t necessarily the richest, they do tend to be better off and host citizens who enjoy a healthy and overall high quality of life.

So, can money buy happiness then?

While both studies showed a strong correlation between happiness and money, neither could determine that money buys happiness. And that makes sense.

Money is a medium of exchange after all. It merely stands in for the things, services, and experiences we purchase with it. So when discussing money and happiness, the question isn’t only how much you have. It’s also how you use it.

If you spend your money on the things, experiences, and necessities that move your happiness dial, then your money will make your life happier. Not perfect. Not blissful. But happier. If you don’t, then your spending habits can actively work against your well-being and life satisfaction.

Elizabeth Dunn, a professor of social psychology at the University of British Columbia, and Michael Norton, a professor of business administration at Harvard Business School, have been studying happiness for more than a decade. Their research shows that part of the reason people with more money are happier isn’t just the size of their bank accounts — it’s how they use their money to generate happiness.

According to Norton, millionaires spend more time and money on active leisure — pursuits like exercise, hobbies, vacations, and social opportunities. The lower you go on the income bracket, the more you find people spending money on passive leisure such as watching TV or even doing nothing.

“It turns out passive leisure makes us unhappy, and active leisure makes us happy. So millionaires — by having more money — actually can buy themselves more active leisure, and that partly predicts why they’re happier people,” Norton told us in an interview.

Another way money facilitates happiness is by bankrolling experiences. People tend to think of money as a way to purchase things, but the joy things provide has a fast half-life. You think that couch is exactly what you need to finally have the living room of your dreams. A few months later, it’s just another thing to sit on.

One reason for this, Norton points out, is that we tend to buy things for ourselves, but we share experiences with others. Even the happiness derived from something like a movie depends on how you approach it. Are you buying a Blu-ray to store on your collection shelf, or are you watching it with friends and then heading to the bar to discuss it?

“Even casual interactions with other people make us happier than sitting by ourselves in a room. So experiences are more interesting and all those things, but they also actually kind of serve to commit us to spending time with other people,” Norton said.

Finally, the more people use their money to give to others, the happier they tend to be. In their research, Dunn and Norton gave participants money to spend in a day. They instructed some participants to spend it on themselves and others to spend it on other people. They found that the charitable groups had a much happier day.

Norton notes that it’s not explicitly the type of giving that matters. People can donate their time or money to charity. They can treat a friend to lunch. Or they can buy a gift for a family member. It’s the act of giving over keeping that moves the happiness dial.

The research shows other ways to use money to facilitate happiness, but the takeaway is this: Yes, the Elon Musks and Bill Gates of the world are probably incredibly happy. But your next big pay raise won’t increase your happiness by much unless you have a plan to spend it wisely.

Learn more on Big Think+

With a diverse library of lessons from the world’s biggest thinkers, Big Think+ helps businesses get smarter, faster. To access Michael Norton’s lessons for your organization, request a demo.