The loneliness epidemic is a myth

- It has become conventional wisdom that society is suffering from an epidemic of loneliness.

- But the research is mixed. While some data suggests that loneliness is prevalent, it is unclear if it is any worse than in the past. Some data indicate that loneliness has decreased.

- By jumping to a wrong conclusion, society risks implementing interventions that don’t work or fail to address underlying causes.

The poet Sylvia Plath once described loneliness as “a disease of the blood, dispersed throughout the body so that one cannot locate the matrix” — an illness both “horrible” and “overpowering.” Given the current research, one would be forgiven for thinking she wasn’t being poetic.

Researchers now know that prolonged loneliness correlates with a range of health problems. Lonely people are at greater risk of stroke, diabetes, dementia, heart disease, and arthritis. They are more likely to suffer from anxiety, depression, eating disorders, alcoholism, and sleep deprivation. In fact, a 2015 meta-analysis determined that the risks associated with loneliness and social isolation were comparable to other health hazards, such as obesity and smoking 15 cigarettes per day.

These data, along with those showing unsettlingly high percentages of lonely people, have led to the widespread belief that we are living through an “epidemic of loneliness.” And world leaders have responded to the perceived public health crisis in kind.

In a recent guest essay for the New York Times, U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy announced a public advisory containing a six-pillar plan to advance social connections. In 2018, then-British Prime Minister Teresa May appointed a minister of loneliness to confront this “sad reality of modern life.” In 2021, the Japanese government appointed its own loneliness minister to counter social ills like hikikomori (“acute social withdrawal”).

“As it has built for decades, the epidemic of loneliness and isolation has fueled other problems that are killing us and threaten to rip our country apart,” Murthy wrote.

There’s no doubt that loneliness is a problem, one that is sadly prevalent and difficult to solve. But the idea that loneliness has exploded into a modern-day epidemic may be overblown, and framing it in such perilous terms may have unintended consequences.

All the lonely people, where do they all come from?

Loneliness is a state of mind arising from a discrepancy between the social relationships a person experiences and those they desire, and this subjective nature makes it challenging to study. A person can look lonely in a café corner while being content to daydream alone. Conversely, someone can be the life of the party while feeling disconnected from the crowd basking in their presence.

To measure loneliness as best they can, researchers typically rely on one of two methods. The first is self-reported questionnaires, such as the UCLA Loneliness Scale. The other is to look at objective markers generally associated with loneliness (whether a person lives alone, is married, has a robust social network, and so on). In both cases, the data do point to potentially troubling trends.

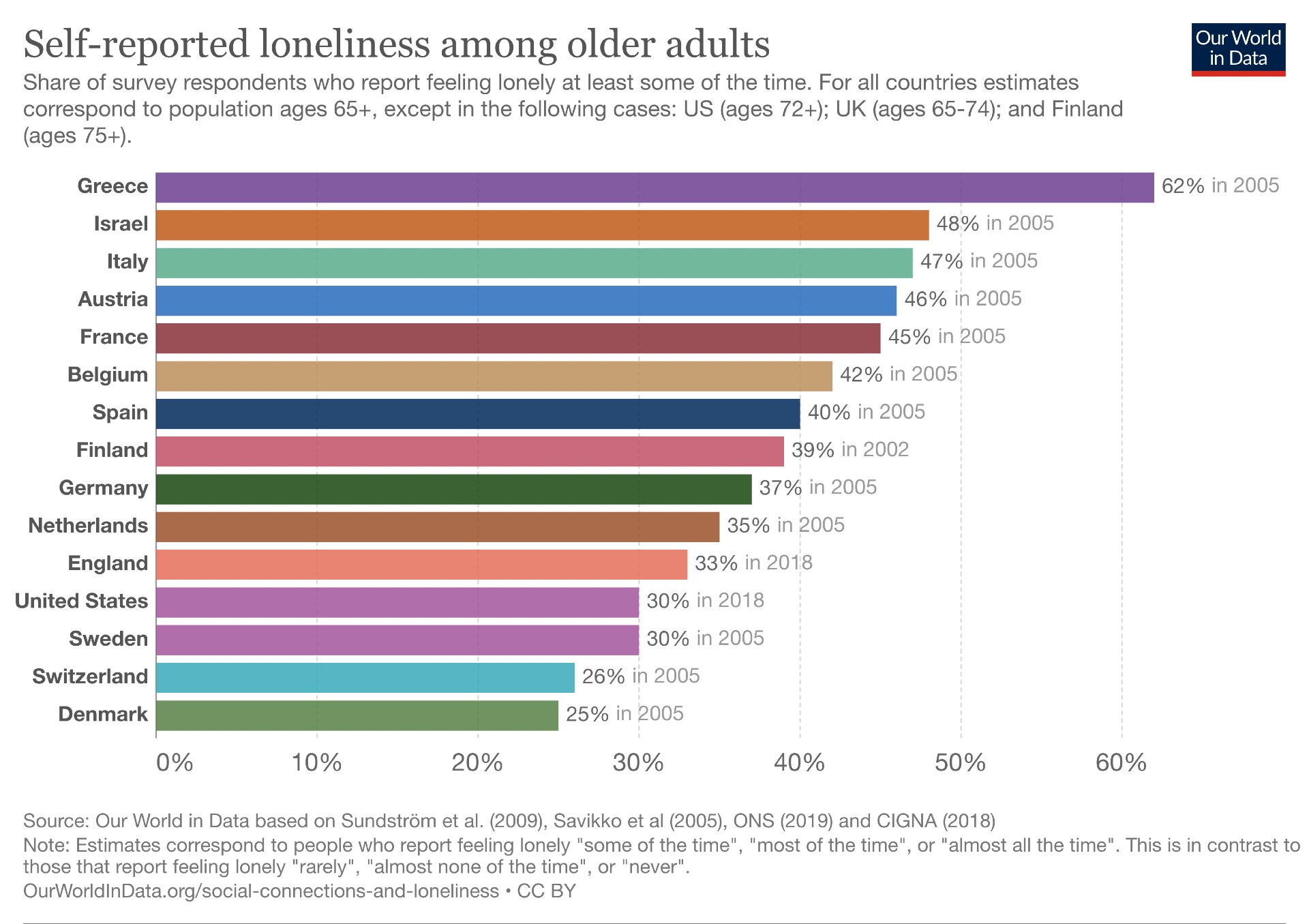

Anywhere from one-third to more than half of American adults described feeling lonely even before the COVID pandemic. Looking outside the U.S., the Jo Cox Loneliness report found that nine million adults in the UK often or always feel lonely. One-third of Chinese older adults report suffering from loneliness. And research compiled by Our World in Data show most older Europeans feel lonely at least some of the time — from a relatively low 25% of adults in Denmark to a striking 62% in Greece.

The picture doesn’t look much rosier using objective markers. In open societies, more people than ever are living alone. One-person households account for more than 40% of all households in Scandinavian nations; more than 30% in France, Germany, and England; and more than 25% in Russia, Canada, Japan, and the U.S. At the same time, friendships appear to be on the decline. According to the 2021 American Perspectives survey, Americans today say they have fewer close friends than they did in the 1990s. Roughly one-tenth report they have no friends at all.

One is (not necessarily) the loneliest number

To be clear, these findings are troubling. Social connection is a fundamental need that, when met, enriches all of our lives. The thought that millions of people are suffering in quiet desperation, potentially right in front of us, is heartbreaking, and they deserve to be a part of the community and in relationships that value them.

When considered critically, however, not all these trends are as pernicious as they first seem, and they certainly don’t prove that loneliness has become an epidemic. To be an epidemic, loneliness must not only be excessively prevalent; it also must have experienced rapid, recent growth compared to historical norms. But the data simply do not bear this out.

To start, visible solitude is a poor metric by which to measure a subjective experience. Yes, more people are living alone. Yes, they may have fewer friends than their (apparently) chummy parents and grandparents. But that doesn’t mean they are lonely.

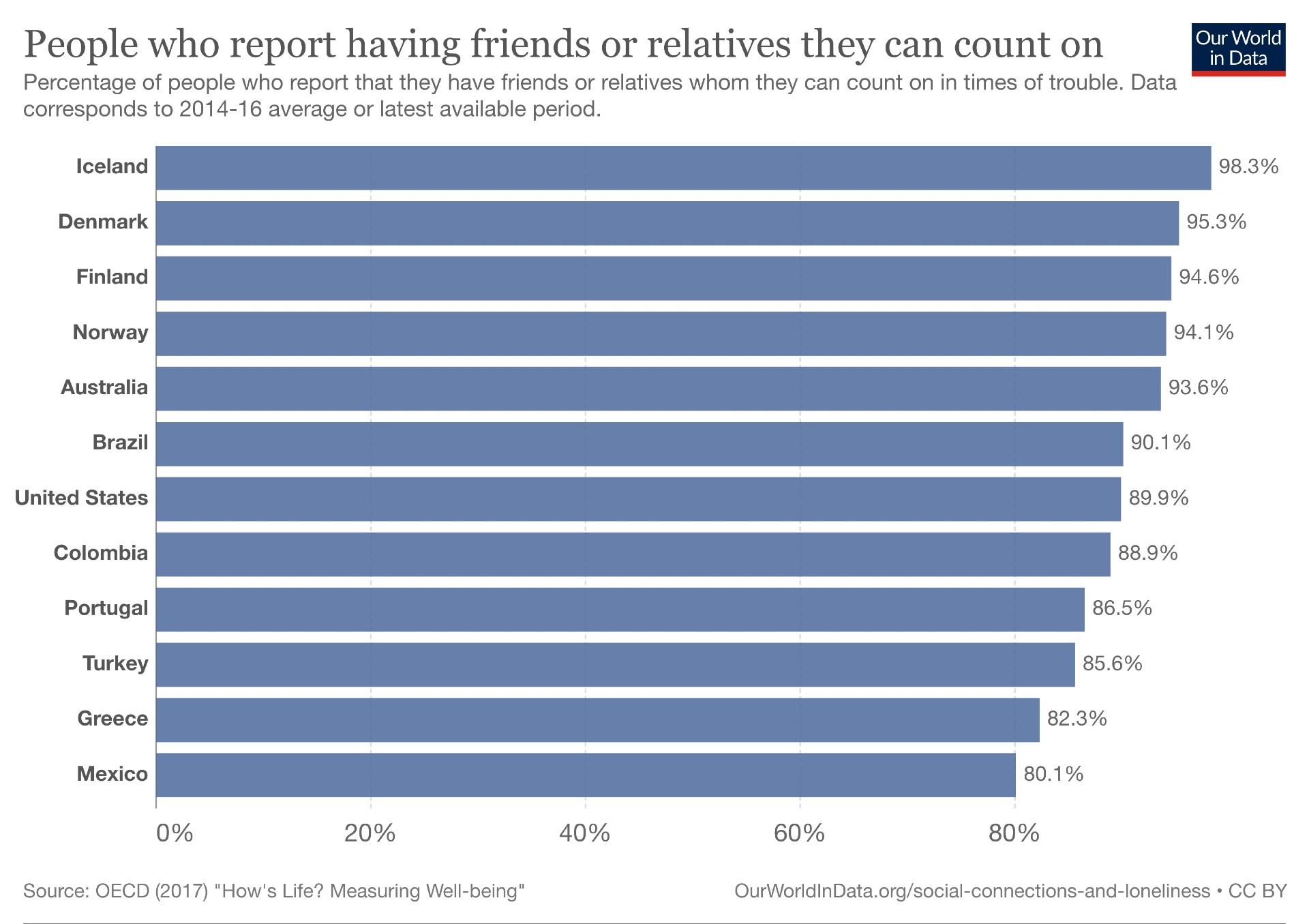

As Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, head of strategy and operations for Our World in Data, notes, living alone is common in Denmark and Switzerland, yet both countries report low levels of loneliness and high levels of social support. He also points to research by Caitlin Coyle and Elizabeth Dugan which shows that loneliness and social isolation do not correlate strongly at the individual level.

The same is true for friend groups. Although larger networks do associate with less loneliness, the effect sizes are small. The number of friends a person has ultimately matters less than the quality of time spent with those friends. One study found that despite having larger social networks, young adults report twice as many lonely days as middle-aged adults. The authors hypothesize that satisfaction with the group — not its size — is associated with less of a sense of isolation.

Even the American Perspectives survey showed that Americans still maintain active, close friendships, just not as many. When asked about satisfaction, roughly 80% of Americans said they were either completely or somewhat satisfied with their friend groups. So while there may be a friendship recession, that’s not the same as a loneliness epidemic.

Are all the lonely people lonelier today?

As for self-perceived loneliness, the data are inconclusive but don’t demonstrate that loneliness has become a modern-day malaise. Some studies even suggest less loneliness exists.

An American Psychological Association study found that loneliness decreased with age until around 70, after which it increased for a variety of health and social reasons. Crucially, the researchers saw no evidence that today’s Americans are any lonelier compared to previous generations or that more of them are lonely. Similarly, the Jo Cox Loneliness report cites “relatively consistent levels of chronic loneliness among older people” and notes that “studies on loneliness have reached different conclusions about the levels and overall distribution of loneliness across the UK.”

Research into young people’s loneliness is also mixed. Data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) shows loneliness at school among 15-year-old students increased in many countries around the world from 2003 to 2018 (with the average rising from 8% to 15%). However, the same dataset showed that students believe they can “easily make friends at school.” The increases were also not across the board. U.S. teens maintained consistent levels of loneliness, while Japanese student loneliness plummeted. Another study, looking at American students only, found loneliness declined between 1991 and 2012.

A loneliness epidemic in name only?

Therefore, the data suggests that loneliness isn’t any worse than it was before. It hasn’t exploded in a sudden outbreak because our environments have made us more susceptible. Instead, it seems that we have uncovered the depths of a problem that has been with us for some time, and the reason is that we’re paying more attention to mental health and caring more about the risks certain marginalized groups face. A problem we should solve? Yes. An epidemic? No.

Beyond perpetuating a falsehood, exaggerating the loneliness “epidemic” creates new problems. One of those is the assumption that loneliness is a consequence of the modern era. Under such an assumption, people will turn their attention to what is different in contemporary society (like social media) and pin the blame on it. Such bias and guesswork often results in society wasting money, time, and other limited resources on solving non-problems or implementing interventions that only cure symptoms while ignoring the underlying cause. Indeed, we have seen such well-meaning waste before, as anyone who remembers California’s ultimately unfounded self-esteem movement can attest.

Consider technology, a go-to boogeyman of modern troubles and one of Murthy’s six pillars. There is evidence that our mental and physical health improve by moderating screen time and social media use, but there is no reason to think that technology addiction is fueling a loneliness epidemic. If that were the case, why do studies show that Japanese and American teens are becoming less lonely? Are they not as plugged in as their Latvian, Spanish, and New Zealander peers? And while excessive social media use is associated with more loneliness and other mental health issues, that doesn’t mean the relationship is causal. Lonelier people may be motivated to engage with social media more to avoid difficult feelings and maintain connections.

“At this point, most policy recommendations for reducing isolation are speculative only,” Eric Klinenberg, a professor of sociology at New York University, writes. ”We lack sound research on the effectiveness of proposed interventions for social isolation, in different contexts and with different populations. It’s time for public health scholars to take on this important challenge.”

Another reason to tread carefully is that loneliness isn’t always a bad thing. Like any emotion, it is a mental state signaling a need for change. When we work too much, move to a new city, or a loved one passes away, life naturally becomes unbalanced. Loneliness reminds us of that fundamental need for human connection. It drives us to strengthen existing relationships or connect with new people.

However, if we over-associate loneliness with sickness — poetic as that association may be — we risk panic that any experience of loneliness is a sign of illness. Painful though it may be for parents and their children, adolescence is an appropriate time to feel the occasional pangs of isolation. Teens are trying to figure out who they are, what relationships they find satisfying beyond their families, and how they can cultivate those relationships through their social connections. Emotions like loneliness are mental tools to help them solve that difficult life transition.

Yes, loneliness can be deleterious if that emotion becomes prolonged or intense, which is what occurred for many during the COVID lockdowns. It can also be dangerous for adolescents who lack the relationships and communal support to help them through. But telling already anxious parents that their child’s loneliness is as hazardous as chain smoking a pack a day is irresponsible. It simply makes an already difficult time all the more fraught.

Learn more on Big Think+

With a diverse library of lessons from the world’s biggest thinkers, Big Think+ helps businesses get smarter, faster. To access Big Think+ for your organization, request a demo.