“The Onion” founder explains his strategy for sparking creativity

- Many people feel motivated to create, but they don’t know where to start.

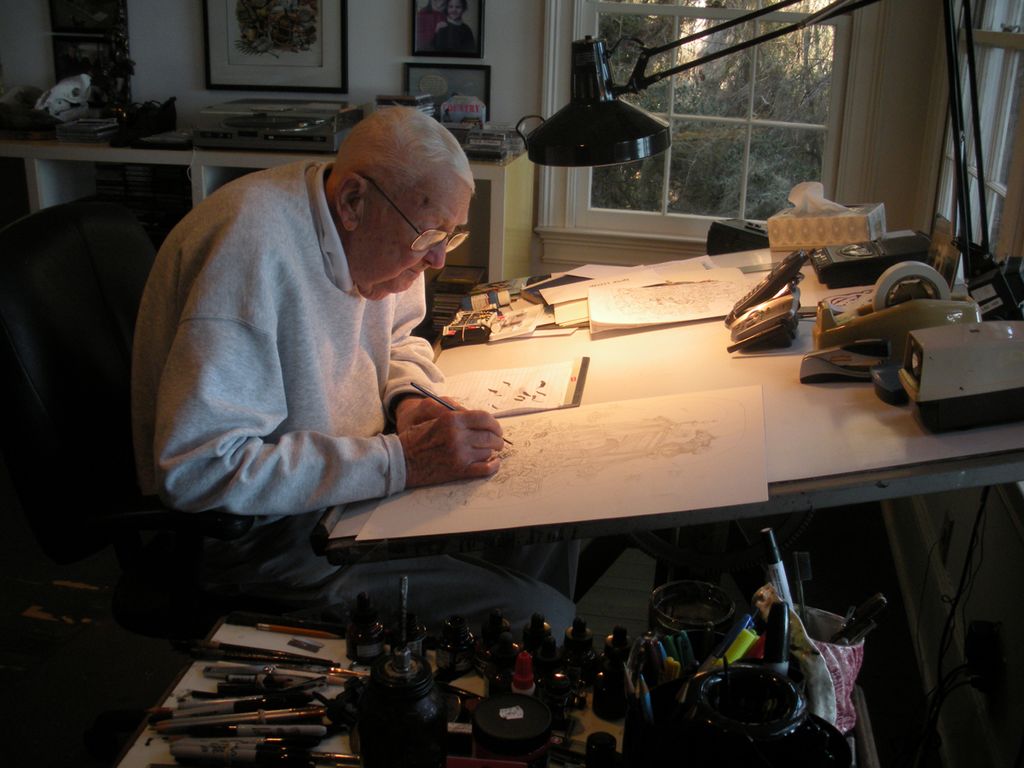

- As a humorist and the longest serving editor-in-chief of The Onion, Scott Dikkers has spent decades honing his strategies for sparking creativity.

- In an interview, Dikkers discusses how to approach the creative process, overcoming its central challenges, and AI’s role in the future of the artistic endeavor.

Many myths have surrounded the creative process. Historically, those myths evoked supernatural forces. The Norse believed Odin could unbind people’s minds with the power of the runes, while the Greeks thought beautiful muses whispered inspiration into the men’s ears.

We may pride ourselves today on being less superstitious, but we still view creativity in magical terms. We just frame it as brain-based magic. We believe creative people are born geniuses or have their brains wired differently or enjoy “ah-ha!” moments in which ideas come fully formed as easily as switching on a light bulb. In reality creativity is — and always has been — a process, one that takes time and discipline to achieve. Anyone with the impulse to be creative can do so, courtesy of our human heritage.

I recently spoke* with Scott Dikkers, humorist and a founder of The Onion, where he served as the comedy website’s longest-running editor-and-chief, to talk about the creative process. We discussed how our minds approach creativity, ways to overcome the pitfalls all creative people face, the value of deadlines, and the role AI and technology will have on how we create, and experience creativity, in the future.

Kevin: Let’s start with why. The creative process can be long. It can be painful, tortuous, and tedious. Yet, people are still drawn to it. Why do you suppose that is?

Dikkers: I have a lot of half-baked theories about that, so I’ll just pontificate on those.

I don’t necessarily think everybody feels the creative compulsion, but those of us who are compelled do it for the same reasons that others climb mountains, fight wars, or do whatever insane Homo sapien thing we’re driven to do. That is to correct some emotional damage from childhood or to make sense of this crazy life. We do it to add structure to life, comment on things, and desperately share our thoughts with other people.

That’s also a critical part of it: to connect and bond with others. Many of the most creative people that I’ve known don’t go to parties. They’re not talkers. They’re alone in their rooms trying to craft jokes. That doesn’t mean they are loners. It’s how they connect with other people. It’s how they build community.

You can’t create with half a brain

Kevin: So, you’re facing your childhood or life’s craziness. Given that, how do people even begin?

Dikkers: That can really stop people because there’s a lot of pressure. Those who have broken through all start the same way. They just start.

They have no idea what they’re doing. It’s just a stream of consciousness or copying other creators. I started cartooning by copying the artists I saw in MAD magazine. I was trying to draw like Don Martin or Jack Davis. That’s a good way to learn as you blunder ahead and try to find your own voice.

And then somebody laughs. Somebody looks at your work and says, “Oh, this is really funny.” You get that spark of connection, that love and attention. That feeds you, and you want to do it more and more. Over time, it starts to feel less stream of consciousness and more like a system. You develop a feel for what works and what doesn’t.

But you have to start. I’m a big fan of the “ready, aim, fire” strategy. I’m also a fan of not letting the perfect be the enemy of the good. Even when you become a seasoned professional, you still have to pour out a lot of crap. You still have to start with that blank page, and nobody is Mozart. Nobody is putting down notes in perfect sequence in their first draft.

Kevin: In your book, you have this concept of the two halves of a comedian’s brain: the clown half and the editor half. I assume other creative types have their version, too. Like musicians have their freestyle side and their composer side.

Dikkers: Totally.

Kevin: How can we tap into those halves while keeping one from dominating the other?

Dikkers: It’s one of the central challenges to being a creative person. A lot of people are stuck in that crazy right-brain side where it’s just create, create, create. They never become good at editing their work. [Others] get stuck on the editor’s side. They are overly critical. They write two or three words and immediately erase them. They can’t get anywhere.

The complete artist or creative is somebody who finds that balance, and the best way to cultivate that is through practice.

When I was the editor of The Onion, I looked at other people’s stories all day, suggesting tweaks and rewrites. But I didn’t generate anything from scratch for a long time. Then we made a TV deal, and I had to write a script. I was like, “Whoa, I got a blank page here. What am I supposed to do?” My creative side had atrophied.

One way around that is this beautiful exercise called “morning pages.” You set an alarm clock for 30 minutes, and you just type or write. Don’t stop to correct anything. Don’t stop to make it good. Just plow ahead. Write about anything while trying not to repeat yourself. This primes the pump and gets the gunk out.

It’s fun, and there’s no harm in it. Nobody is ever going to see these morning pages. You can delete them as soon as you finish, or if you find some gold, you can save it somewhere. But after two or three days of doing that, good luck stopping me from sitting down and writing a rough draft.

The complete artist or creative is somebody who finds that balance, and the best way to cultivate that is through practice.

Scott Dikkers

Then you need to cultivate the editor’s side. After finishing a rough draft, take a break from it and go write something else for a few days, weeks, or months (everybody’s different). Then come back to it and look through what you wrote. Have other people look at it. Get some real editor-minded feedback and implement it.

Having that balance is like a muscle. The more you exercise it — the more you try to do it faster, in different ways, at different times, and so on — the more easily you can move back and forth between the creative and editorial sides with dexterity.

Rolling out the red carpet

Kevin: The Onion started as a newspaper and then moved online in … 1996? 1997?

Dikkers: It was about 1995.

Kevin: Firmly in the Netscape era of the internet?

Dikkers: It was the very first humor website.

Kevin: Wow.

Dikkers: It was a strange time. I think it was $450 to buy the domain, theonion.com. There was no GoDaddy. It was like … I forgot. I forget what we had to deal with. [Laughs.]

Kevin: No one was holding the domain to sell it to the National Onion Association?

Dikkers: No, no. It was before domain squatting was a thing.

Kevin: Have you noticed any changes in how people create in that time? Like maybe the rush of creating things online limits the amount of time anyone has to sit with their editor or clown sides?

Dikkers: I think so. That is partly why I feel like it’s so important to develop that dexterity. Things move fast online. You don’t want to waste people’s time or bore them. It all has to be accessible.

Before The Onion, way too much humor writing was presented as a big block of gray copy. Why would anyone be incentivized to read that? The headline wasn’t even funny. The funny part was the punchline at the end.

And I thought, “No, you’ve got to flip that.” You have to make the headline funny, and then everything after that should get funnier and funnier. So, if you just want to read the headline, get a chuckle, and go about your day, God bless you. But if you want to read on, we’re going to make that as easy for you as possible, and we’re going to reward you by making the jokes funnier the further you go. It’s all about rolling out the red carpet for the reader to make it easy for them to come into this.

I focused on the written word in How to Write Funny because it is the most challenging. It’s like pulling teeth to get people to look at writing and actually read it. And the writer’s job is to figure out how they are going to do that. What incentives are they putting out there? What trail of breadcrumbs are they leaving?

In other media, if you apply the same principles, you’re going to do gangbusters because you get more leeway from an audience when you’re talking about a video or a movie.

Kevin: That’s true. I rarely walk out of a movie even if I hate it.

Dikkers: Yeah, it’s a big decision. Am I going to walk out of this movie? I paid 20 bucks to sit here. Yeah, they need to work really hard to make me walk.

Kevin: [Laughs.] Whereas I’ve put down more than a few books in my time.

Dikkers: Oh yeah. I’ve read the first 30 pages of so many books.

A sophisticated game of peekaboo

Kevin: As you say, writing is difficult, but comedy writing is especially challenging. So much of stand-up is tone, delivery, and stage presence. Write many of the same jokes down on paper, and I just don’t think they work.

Dikkers: Exactly. You’ve got none of that context. I talk about that quite a bit in the book, and it’s another reason why I focused on the written word in comedy. It’s the hardest thing in any type of creative medium, but if you can write great material and take it to stand-up, all those other tools will only make the material better.

This is how Chris Rock works. He writes really great material and then tests it by flatly reading it. He judges what gets a good response from others, and then he refines it and gives it attitude. Throws in a few F-bombs. Adds in a little body language.

When you’re stuck with the written word, you have to design other ways to connect with the reader. So, I devised this idea of funny filters, which are these literary devices that almost do the job of the in-person performance — that feeling of deep connection.

Kevin: One of your examples in the book is Jonathan Swift’s recommendation that we should eat poor babies to take care of the hunger problem. Two birds, right?

Dikkers: [Laughs.] Exactly.

Kevin: His hyperbole does create a tone and voice similar to what somebody can have on the stage.

Dikkers: Yeah. It’s like you’ve got a secret, and you’re making the reader itch to know what it is. I love that idea of the intelligence behind the text. The reader wants to connect and figure out what you’re thinking. They have fun opening the curtain and seeing who that crazy person is behind there.

On-the-nose text is something you always want to avoid. You know, just typing exactly what you think. It’s so much more fun to wear a mask and filter it through any number of literary devices. In the book, I go through the 11 funny filters that can create that facade for the audience.

One of my favorite examples of this is Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. The book is written in Huck Finn’s voice. He’s this 13-year-old, uneducated kid, and he’s really interesting and funny, but you can also sense this grizzled, sarcastic wisdom behind that voice.

This goes back to one of the deepest, most satisfying things for the human to experience in entertainment, which is the peekaboo. Babies go crazy for it, and we still have that in us. We just require a more sophisticated version of it.

That’s what we do when we hide subtext in a piece. We toy with the audience’s expectations and give them little clues to let them figure out what it is we’re really saying. It’s a bit of, “Whoa, wait a minute. Where — oh. There he is!”

Kevin: And it makes the reader feel smart. Like they’ve cracked the code.

Dikkers: Totally.

Kevin: Like those babies you mentioned. They must feel like geniuses. Like, “I found you! You tried your best to hide from me, but I’m too smart.”

Dikkers: I’m figuring out object permanence, damn it!

Kevin: [Laughs.] Then there’s the other side. As a writer, when you master that, you probably feel the same joy and pride as a parent.

Dikkers: To have someone else in the palm of your hand cracking up at what you’ve concocted. It’s a ton of fun.

The quick and the deadlines

Kevin: I want to get back to the editor’s brain because I do think this is where a lot of creative people become trapped.

When someone is too much of an editor, they may tinker with something to the point of breaking it. I imagine a lot of painters have created perfectly happy little bushes and then kept going until it became a tragic little shrub in the corner of the frame.

What strategies do you use to help you know when enough is enough?

Dikkers: It takes a lot of experience to gain some of that wisdom, but I’ll tell you something that helped me a lot in my early years, and I recommend this to everybody. Give yourself a deadline.

For me, that was doing a daily comic strip. I had to deliver it to the newspaper, or they would have a blank space where my comic went. I did that with The Onion, too. We sold advertising, and we had to get those newspapers out. Later, we had to get the website out to fulfill contracts with advertisers. We couldn’t afford to have a blank space.

When we were online — maybe five, six years in — we started this thing called Drupal editing where you could go in and edit stories after they had been published. And it was an addictive curse. Too many of the writers on staff would go in and tweak their stories. I had to take the password away because they had lost that critical step in the process where you say it’s done. You got to get it out, learn from it, and move on to the next thing.

So again, don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good. Do the best you can. Finish it as best you can. Then what you do is get feedback from audiences and learn. You figure out, “Ah, I rushed that one” or “That one worked well” or “Maybe I could do this better next time.” That’s how you gain that wisdom and experience.

Kevin: I can see that. When I have a deadline, the project gets done. It’s those projects I file under “someday” that languish.

Dikkers: And are they any better? Not really. There’s something to be said for being a craftsman and churning out work.

Right now, I’m working on a graphic novel, and I’m looking at other comic book artists — people like Jack Kirby and Bill Sienkiewicz. These are great artists who were on a really tight treadmill to produce. Sometimes, a week or two. But you look at it, and it’s just masterful.

Would it have been any better if they had another month to work on it? Yeah, there might have been more detail, but at some point, it’s overkill. At some point, you need to do the work that fits a reasonable amount of time and get it out. It’s probably going to be better than work you labor on for way too long.

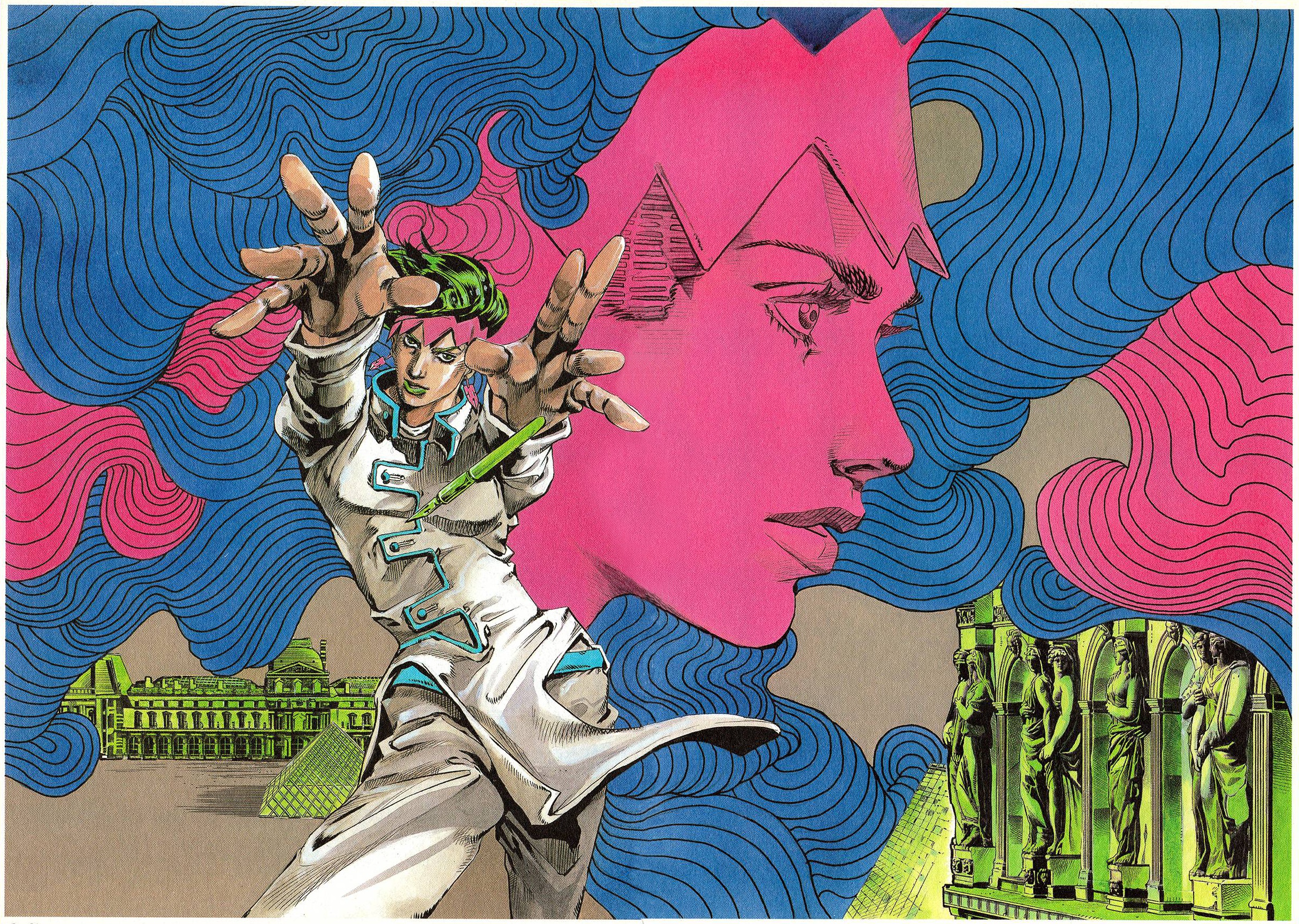

Kevin: I love to read manga series that have been ongoing for decades and see the progression of the artists. Titles like JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure and Berserk. It’s incredible the difference 30 years of deadlines, dedication, and craft can make.

Dikkers: Exactly. You get to be such a master. What people don’t realize is that you aren’t going to develop those skills working on one project for six years. If you did a project every six months for six years, you’d finish 12 projects, and you’re going to be a lot more skilled than the person who literally worked on one project and didn’t even finish it. And that’s really sad.

Kevin: Like The Confederacy of Dunces, which is a great book.

Dikkers: Absolutely.

Kevin: But John Kennedy Toole became so despondent and depressed over the process.

Dikkers: That he killed himself.

Kevin: Yeah.

Dikkers: Some movies perpetuate the myth of the genius who spends years working on something. But that’s the exception that proves the rule. I wouldn’t recommend it to anybody. You could say it worked out great for him. It’s a great book. But he’s dead so he doesn’t get to enjoy it.

Finding your critical darlings

Kevin: How do you handle criticism of your creative work?

Dikkers: I’m a big fan, and I love when it comes hard and negative. I just wrote a novel and sent it to beta readers. One of the most helpful critiques I received was from somebody who hated it.

Backing up: I have this form that I have my beta readers fill out. On it, I ask for five things that aren’t working.

Kevin: Good idea.

Dikkers: Well, he filled that out and then sent me 12 additional pages of notes. It was an absolute treasure trove. [Laughs] And I may never win him over. This might not be his genre, his story, or his book. But I want the chance to appeal to that person. When I look at those notes, I do it with that pure editor brain. I think of it like a scientist, and that’s a very important process.

I’ve done books where I’ve had, like, a hundred beta readers, and they’ll all have a problem with a certain chapter or a story turn or something like that. And then I know: That’s a problem! That needs to be fixed. Then I come up with these organic fixes that elevate the whole project.

Because comedy is a social art. It only works if other people think it’s good. There’s only a handful of Mozart-level geniuses who can write jokes alone in a closet and then present them to an audience and have them all work. The rest of us mortals need to test our material. We need to see if it works and then go back to the drawing board.

Just remember that there’s only one rule [in comedy]: If they laugh, it’s funny.

Scott Dikkers, “How to Write Funny”

Kevin: I seem to recall that Mozart’s father began teaching him at the age of three. I don’t imagine there are many comedians out there drilling their three-year-olds on the art of comedy.

Dikkers: You’d be surprised. I think the reason why Mozart was so talented was because music was a basic way of life and communication for him from a very young age. By the time he was a teenager, he had clocked in Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000 hours and was already a master.

The same thing is true with comedy people. Some develop those skills because of the position they have in the family or because they don’t get along in school. They have to be the peacemaker or the class clown. They have to be the one who keeps things light and funny. So, in many ways, it is drilled into them. When they turn 18, they are a Chris Farley or Eddie Murphy or Chevy Chase. Somebody who uses humor as a basic way of communicating.

It may be less formalized, but they internalized it all the same through those life processes.

On the other hand, some do formalize it. I knew I wanted to do this, so I studied other comedians. I would record late-night comedy shows on TV. I would literally use a tape recorder when I was a preteen, and I would study the structure of jokes. It was all so fascinating to me. So, I was in comedy school my whole life, and I don’t think I got good at it until I was in my mid-twenties. It took those 10 years that it takes anybody to get good at anything.

That’s what stops a lot of people from being creative. You have to be propelled by a love of it, and you have to not care that you suck and keep doing it anyway. Childhood is a great time to do that because you’re getting all this positive reinforcement regardless. That’s a critical part of the recipe for building talent.

Kevin: Yeah.

Dikkers: I could learn to speak French like a native speaker if somebody would just treat me like a French infant for five years. I would be the most amazing French speaker in the world. Same thing with learning comedy or music or anything else.

Kevin: There’s a new business model for you there.

Dikkers: Yeah. I’ll treat you like an infant for five years. [Laughs] Total immersion.

Kevin: [Laughs] You see the Yelp reviews: “The peekaboo sessions were amazing.”

Dikkers: Exactly. I particularly enjoyed the diaper changing and the feedings.

Kevin: That’s a different kind of service I think.

Dikkers: No, you’ve got to do the full service. Get it 24/7.

Kevin: [Laughs]

The soul and the machine

Kevin: We discussed The Onion’s move from newspaper to online, but now everyone is moving into the era of AI and ChatGPT. How do you see AI changing the creative process — not only in how we are creative but how we experience creative works?

Dikkers: Thanks for asking about that. I like entertainment like anyone else, and I absolutely hate AI-generated entertainment. I have zero interest in it. I will always pay a premium for human-created entertainment. I don’t care how good AI gets.

Having said that, I don’t know how things will change. Digital art can be amazing. If digital storytelling becomes amazing, maybe I’ll enjoy it. But a part of the process for me is the connection. Somebody is communicating something to me. There has to be a soul for entertainment to work for me.

Now, I do predict a future when humans are extinct, and AIs will create amazing entertainment for themselves. I just don’t think we’ll be there to enjoy it.

Kevin: [Laughs]

Dikkers: From a creator standpoint, I love it as a tool. Absolutely love it. I use AI to generate reference art for drawing or synonyms for writing. I love tools. As soon as word processing became a thing, I jumped right on it. I loved it. As soon as spellcheck became a thing, it was like my best friend. I’m going to take advantage of these tools, but I’m never going to have AI do my creative work for me.

Kevin: Did you see that endless Seinfeld episode created entirely by AI? What were your thoughts there?

Dikkers: Yeah. Again, it comes down to not feeling a soul. Every good piece of creative work has some sort of vision behind it. There’s so much nuance that goes into how a joke is worded and communicated to express the thought you want. Only humans can do that thinking.

The AI-generated Seinfeld episodes that I saw feel like bad Saturday morning cartoons used to be. They were totally formulaic. They reused animation loops. Very unsatisfying. It might be a thing that exists, but it’s going to be premium to get the human-generated stuff.

The core takeaway is not everybody is necessarily destined to be creative, but if you feel the compulsion, listen to that. That’s an important part of yourself.

Scott Dikkers

Shine on, you creative diamond!

Kevin: Is there a message that you would like to leave for people looking to be more creative in their lives?

Dikkers: The core takeaway is not everybody is necessarily destined to be creative, but if you feel the compulsion, listen to that. That’s an important part of yourself. Jump into it. Don’t worry about being great because you only get great by doing it. So whatever medium, field, or genre you want to work in, just start. It’s going to feel amazing.

It won’t always be good. Be okay with that. Celebrate yourself. Find someone who can tell you how great everything is for the first five years. Also, don’t focus on one thing. Work on a ton of projects. Work in different media. Try different things. But do them fast. Churn them out because you learn by creating one thing from start to finish. You don’t learn by creating one thing for 10 years. That’s a recipe for frustration and disappointment — not self-actualization.

Kevin: Thank you, Scott. I truly appreciate this conversation.

Dikkers: Thank you. I enjoyed it quite a bit.

Kevin: Where can people find you online to learn more about the creative process in general or comedy writing specifically?

Dikkers: Yeah, howtowritefunny.com is the main conduit where I do stuff. I also put out a daily comedy, creativity, or productivity tip on my Substack, “No Dikkering Around.” Just google my name, and you’ll find a bunch of stuff. Even if you spell my name wrong, Google is smart enough to find me. Spell it however you want.

Kevin: [Laughs.]

Learn more on Big Think+

With a diverse library of lessons from the world’s biggest thinkers, Big Think+ helps businesses get smarter, faster. To access Big Think+ for your organization, request a demo.

*Note: This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.