Did ancient Greek philosophers believe in aliens?

- Speculation about alien life dates back to the ancient Greeks, and perhaps even further.

- The Scientific Revolution expanded our vision of the Universe and revived our belief in the possibility of extraterrestrial life.

- Unfortunately, the lack of convincing evidence has ushered in a new age of cosmological pessimism.

The concept of aliens is quite old. Long before human civilization developed a scientifically accurate understanding of the cosmos, people across the world looked up at the sky and wondered what was out there. Some ancient societies populated this vast, mysterious expanse with gods: entities responsible for creating the sun and moon and stars. Others took those same celestial bodies to be similar to Earth, and therefore inhabited by organisms not unlike ourselves.

In his book Extraterrestrials, science and technology writer Wade Roush traces the history of alien speculation across nearly two and a half millennia. This history begins with the ancient Greeks and stretches up until the most recent Mars rover expeditions. Along the way, Roush illustrates how the world we live in shapes the way we conceive of the worlds that might exist in outer space. The history of alien speculation is not only the history of science, but also the history of religion and popular culture.

Greek antiquity

In the past, people were often persecuted for thinking differently. This was true even in ancient Greece, a setting renowned for its trailblazing philosophers. When the philosopher Anaxagoras — who sought to provide scientific explanations for seemingly supernatural phenomena like eclipses and rainbows — suggested that “the moon is not a god but a great rock and the sun a hot rock,” he was arrested and sentenced to death. Anaxagoras would have met a fate similar to Socrates, but was banished instead of killed thanks to the pleading of his friends.

Anaxagoras also considered the possibility that the moon might be inhabited, a highly controversial supposition that contradicted the dominant view of the cosmos as outlined by Plato and Aristotle. Plato, who separated reality between forms and shadows, refused to acknowledge the existence of worlds other than our own. Aristotle also rejected the so-called plurality-of-worlds theory because it could not be reconciled with his understanding of gravity, which posited Earth as the one and only center of the universe.

Our understanding of astronomy rests not on the shoulders of Plato and Aristotle but their oft-forgotten contemporaries. Anaximander, writes Roush, “was the first to propose that Earth is a body floating in an infinite void, held up by nothing.” Democritus, starting from the premise that there existed an infinite number of atoms, argued there must also exist an infinite number of worlds. “It seems absurd,” one of his pupils is believed to have said, “that in a large field only one stalk should grow, and that in an infinite space only one world exists.”

Belief in the existence of other worlds caught on with a number of philosophers, including Epicurus, who once wrote to the historian Herodotus that “there is an unlimited number of cosmoi, and some are similar to this one and some are dissimilar.” This belief, however faint, survived in ancient Rome. “Nothing in the universe is unique and alone,” the Roman poet Lucretius once wrote, “and therefore in other regions there must be other earths inhabited by different tribes of men and breeds of beasts.”

The Scientific Revolution

Although Plato and Aristotle lived in a pre-Christian world, their ideas about the universe helped shape the doctrine of the Christian faith. During the Middle Ages, this faith proclaimed that Earth was created by God as the center of the universe. The story of Jesus Christ, who sacrificed himself to absolve the sins of man, reestablished humanity as the most significant of all creations. If other worlds existed, they could not possibly be inhabited. For if they were, this would automatically diminish the significance of the crucifixion.

Church doctrines did not stop Polish polymath Nicolaus Copernicus from writing On the Revolution of the Celestial Spheres, but they did prevent him from publishing it. The book, not released until his death in 1543, mapped out an interplanetary system organized not around the Earth but the sun. This “heliocentric” model explained phenomena the Aristotelian model could never account for, including retrograde motion. It also confronted Copernicus’ readers, as Roush puts it, “with the idea that we live on a planet that is just like any other.”

The Dominican friar, mathematician, and cosmological theorist Giordano Bruno did not wait until his death to share his ideas about the universe. In three dialogues, published between 1584 and 1591, Bruno speculated that some distant stars might be suns as well, that these suns were orbited by planets of their own, and, last but not least, that some of these planets might be inhabited by life similar to Earth. While those views might have been annoying to the Church, Bruno’s interest in magic and occultism is probably what resulted in his arrest in 1592. Refusing to recant, he was burned at the stake after seven years of imprisonment and torture.

The German astronomer Johannes Kepler lived and worked under different circumstances. Kepler was born in Germany after the Protestant Reformation, meaning he could publish his research without fear of persecution. He was especially influenced by Galileo Galilei’s discovery of Jupiter’s moons, which orbited the planet in much the same way the Earth orbits the sun. “Each planet,” Kepler concluded after reading Galileo, “is served by its own satellites. From this line of reasoning we deduce with the highest degree of probability that Jupiter is inhabited.”

A new era of disbelief

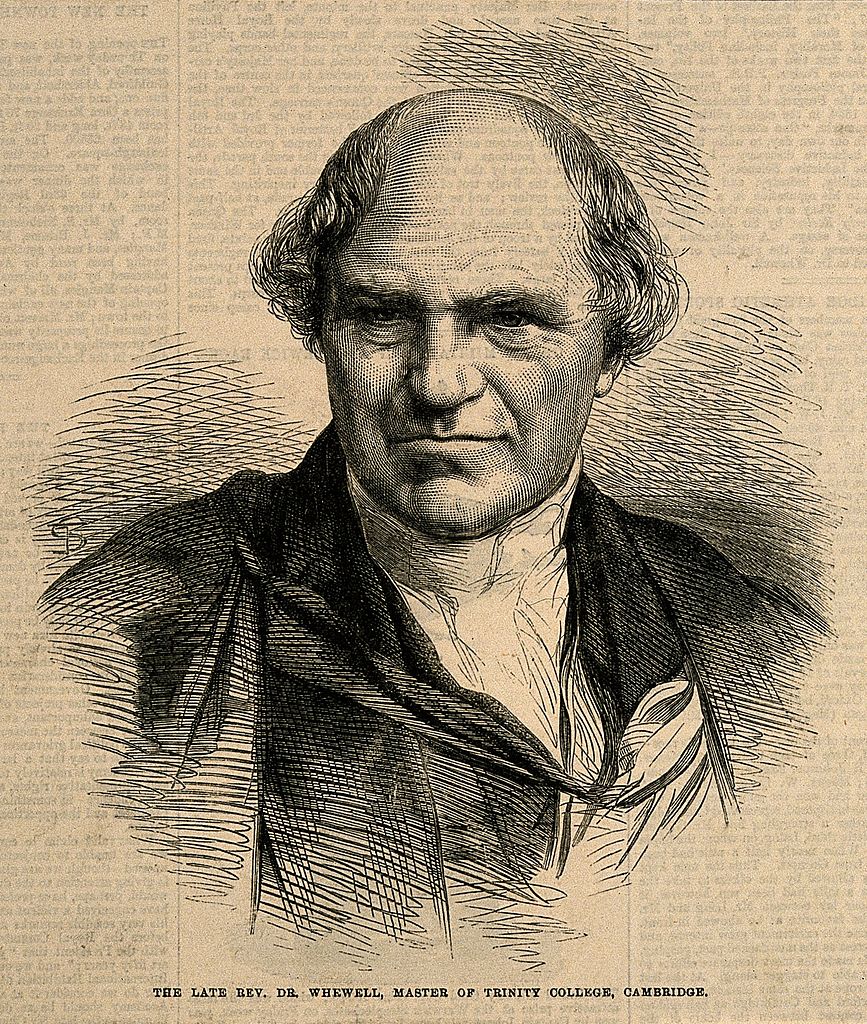

Not every participant of the Scientific Revolution believed in the existence of aliens. Galileo, a devout Catholic, regarded speculation about aliens as “blasphemous.” The British polymath William Whewell argued against the pluralism-of-worlds theory to defend the special connection between God and mankind. Ironically enough, his religiously motivated thesis, outlined in an 1853 book titled Of the Plurality of Worlds, proved to be more scientifically accurate than the heathen astronomers he was criticizing.

Roush summarized Whewell’s ingenious but convoluted essay as follows: “If Earth had been, in effect, uninhabited through most of its history, then it wouldn’t be surprising if other distant planets were also empty.” Most stars, Whewell adds in his own words, “are within a nebular region, which may easily be uninhabitable. And where this nebular region, marked by zodiacal light, terminates, the world of life begins, namely at the Earth.” He concludes that the absence of life does not make the cosmos any less interesting or majestic.

Whewell found an ally in Alfred Russell Wallace, a British naturalist co-credited with formulating the theory of evolution through natural selection alongside Charles Darwin. “Our earth is almost certainly the only inhabited planet in our solar system,” Wallace wrote in 1903, a time when the scientific community was actively debating whether Mars was hiding intelligent life. Even if life existed elsewhere in the universe, Wallace was of the unshaken opinion that it could never attain the levels of complexity we find on Earth.

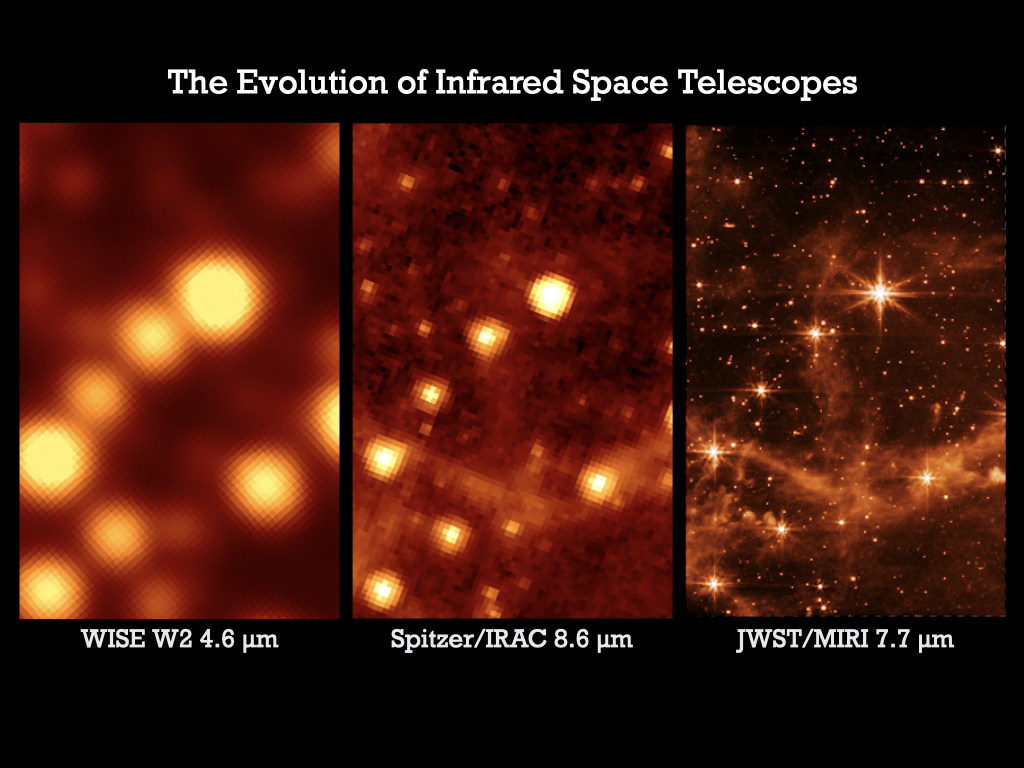

Although Whewell and Wallace were ignored by their contemporaries, their writing set the stage for a new age of cosmological pessimism — namely, an ongoing period in which aliens are the stuff of science fiction and each increasingly comprehensive venture into outer space (whether through exploration or observation) fails to yield even the slightest evidence pointing toward the existence of beings that Democritus and Anaximander believed ought to exist.