The Economic Weapon: How sanctions became a tool of modern war

- President Woodrow Wilson described economic sanctions as a tool “that brings a nation to its senses just as suffocation removes from the individual all inclinations to fight.”

- Because it was inspired by blockades, the League of Nations referred to sanctions as an “economic weapon.”

- The methods of economic warfare have been repurposed and refined for use outside a formally declared state of war. What made interwar sanctions a truly new institution was their application during peacetime.

Excerpted from The Economic Weapon: The Rise of Sanctions As a Tool of Modern War © 2022 by Nicholas Mulder. Reprinted with permission from Yale University Press.

Can war be banished from the earth? Throughout modern history, world peace has been a powerful ideal. It has also been one of the most elusive. Each major war produced its share of cynics as well as visionaries. Pessimists saw war as an inescapable part of the human condition. Optimists viewed growing wealth, expanding self-government, and advancing technology as drivers of slow but steady moral progress. This veering between hope and desolation took on a new urgency after the unprecedented destruction of World War I. The victors created a new international organization, the League of Nations, which promised to unite the world’s states and resolve disputes through negotiation. The collapse of the global political and economic order in the 1930s and the outbreak of a second world war have made it easy to dismiss the League as a utopian enterprise. Many at the time and since concluded that the peace treaties were fatally flawed and that the new international institution was too weak to preserve stability. Their view, still widespread today, is that the League lacked the means to bring disturbers of peace to heel. But this was not the view of its founders, who believed they had equipped the organization with a new and powerful kind of coercive instrument for the modern world.

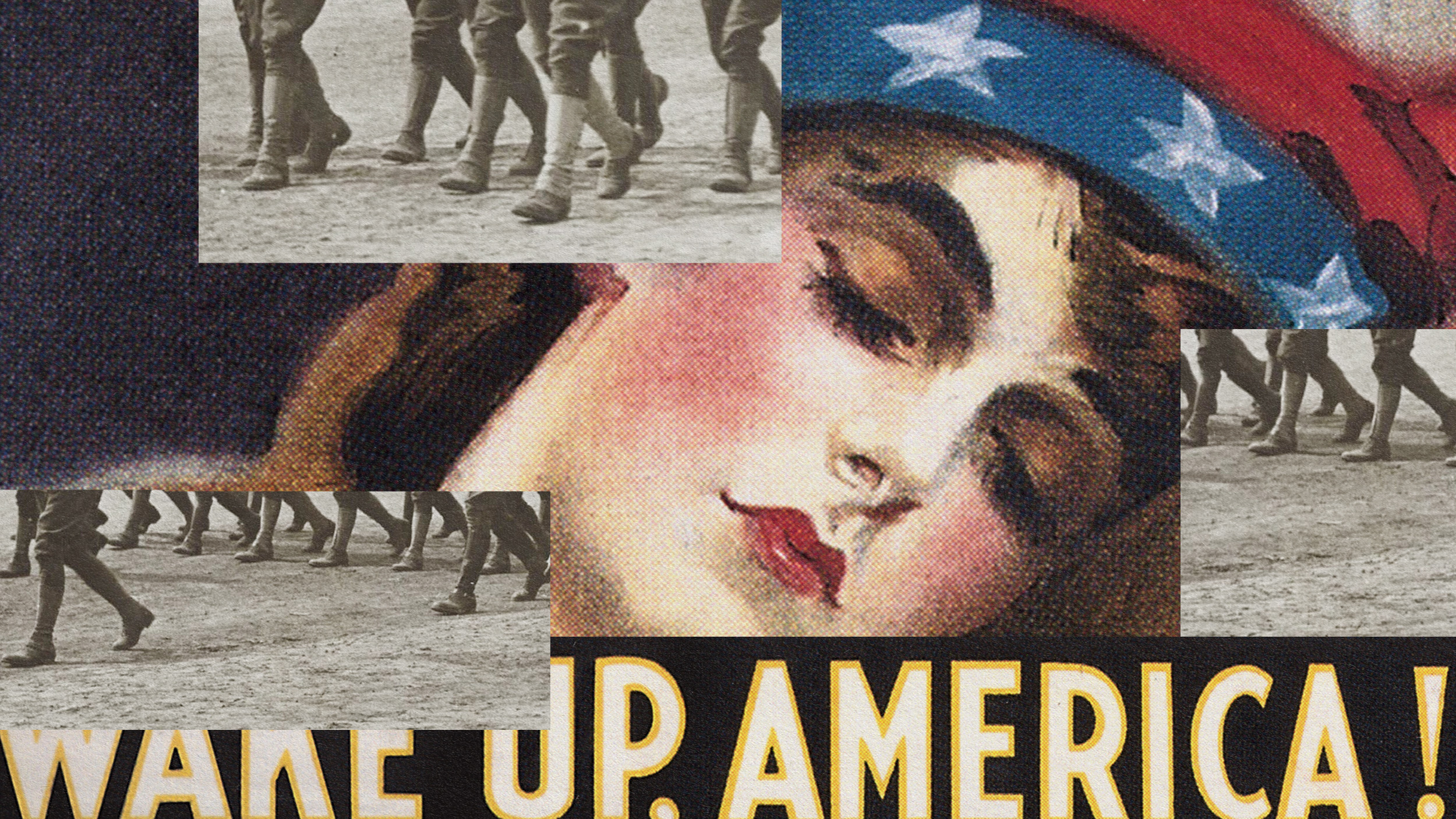

That instrument was sanctions, described in 1919 by U.S. president Woodrow Wilson as “something more tremendous than war”: the threat was “an absolute isolation… that brings a nation to its senses just as suffocation removes from the individual all inclinations to fight… Apply this economic, peaceful, silent, deadly remedy and there will be no need for force. It is a terrible remedy. It does not cost a life outside of the nation boycotted, but it brings a pressure upon that nation which, in my judgment, no modern nation could resist.” In the first decade of the League’s existence, the instrument described by Wilson was often referred to in English as “the economic weapon.” In French, the Geneva-based organization’s other official language, it was known as “l’arme économique.” Its designation as a weapon pointed to the wartime practice of blockade that had inspired it. During World War I, the Allied and Associated Powers, led by Britain and France, had launched an unprecedented economic war against the German, Austro-Hungarian, and Ottoman empires. They erected national blockade ministries and international committees to control and interrupt flows of goods, energy, food, and information to their enemies. It was the severe impact on Central Europe and the Middle East, where hundreds of thousands died of hunger and disease and civilian society was gravely dislocated, that made the blockade seem such a potent weapon. Today, more than a century after the Great War, these measures have a different but more widely known name: economic sanctions.

How economic sanctions arose in the three decades after World War I and developed into their modern form is the subject of this book. Their emergence signaled the rise of a distinctively liberal approach to world conflict, one that is very much alive and well today. Sanctions shifted the boundary between war and peace, produced new ways to map and manipulate the fabric of the world economy, changed how liberalism conceived of coercion, and altered the course of international law. They caught on rapidly as an idea propounded by political elites, civic associations, and technical experts in Europe’s largest democracies, Britain and France, but also in Weimar Germany, in early Fascist Italy, and in the United States. But then as now, sanctions aroused opposition. From the outbreak of war in 1914 until the creation of the United Nations Organization in 1945, a diverse assortment of internationalists and their equally varied opponents engaged in a high-stakes struggle about whether the world could be made safe for economic sanctions.

When the victors of World War I incorporated the economic weapon into Article 16 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, they transformed it from a wartime to a peacetime institution. Like other innovative aspects of the League’s work in the realms of global economic governance, world health, and international justice, sanctions outlived the organization itself and continued as part of the United Nations after World War II. Since the end of the Cold War their use has surged; today they are used with great frequency. In retrospect the economic weapon reveals itself as one of liberal internationalism’s most enduring innovations of the twentieth century and a key to understanding its paradoxical approach to war and peace. Based on archival and published materials in five languages across six countries, this book provides a history of the origins of this instrument.

The original impulse for a system of economic sanctions came at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference from the British delegate, Lord Robert Cecil, and his French counterpart, Léon Bourgeois. These men were unlikely partners. Cecil, an aristocratic barrister and renegade member of the Conservative Party, was a fervent free trader who became Britain’s first minister of blockade during the war; Bourgeois, the son of a republican watchmaker, worked his way up the professions to become a Radical Party prime minister in the 1890s and advocated a political theory of mutual aid known as “solidarism” (solidarisme). But despite these different backgrounds, both Cecil and Bourgeois agreed that the League could, and should, be equipped with a powerful enforcement instrument. They envisioned deploying the same techniques of economic pressure used on the Central Powers against future challengers of the Versailles order. Such recalcitrant countries would be labeled “aggressors” — a new, morally loaded legal category — and be subjected to economic isolation by the entire League. The methods of economic warfare were thus repurposed and refined for use outside a formally declared state of war. What made interwar sanctions a truly new institution was not that they could isolate states from global trade and finance. It was that this coercive exclusion could take place in peacetime.