Pax Economica: The forgotten history of the free-trade movement

- Today, free trade is often associated with capitalism and democracy.

- In past centuries, it enjoyed support among socialists and other activists who hoped to establish a more egalitarian world order.

- In his latest book, historian Marc-William Palen revisits their ideas by exposing the age-old link between protectionism and imperialism.

In the 1927 musical Strike up the Band, a struggling American cheesemaker catches a much-needed break when the United States government slaps a tariff on the import of Swiss cheese. Hoping to drive his overseas competitors out of the market for good, he comes up with a seemingly absurd but quite logical plan. Outside of working hours, he sets up an organization called the Very Patriotic League to spread anti-Swiss sentiment and, eventually, campaign for a full-blown invasion of the Alps. When the tariff war turns into an actual war, the cheesemaker emerges as the richest man in town.

Today, tariffs and other forms of economic protectionism are commonly associated with socialism and authoritarianism, while open, unregulated markets are seen as agents of capitalism and democracy. In the not-so-distant past, things were a little different. As historian Marc-William Palen shows in his latest book, Pax Economica: Left-Wing Visions of a Free-Trade World, protectionism was a weapon that Western countries used to control and exploit their colonies. In this age of empire, left-wing political groups saw free trade not as a threat, but as a means to create a different, more egalitarian world order.

Age of empires

Economic protectionism is intrinsically linked with imperialism. As early as the 1660s, England passed laws preventing its North American colonies from selling profitable goods like sugar and tobacco to anyone except the British, thus making their economy fully dependent on the motherland. Wanting to keep the spoils of their colonies for themselves, other European countries followed suit. “Pretty much every single rival to the British Empire from the 1870s onwards was turning to protectionism and neomercantilism, carving out territories for exploitation,” Palen tells Big Think.

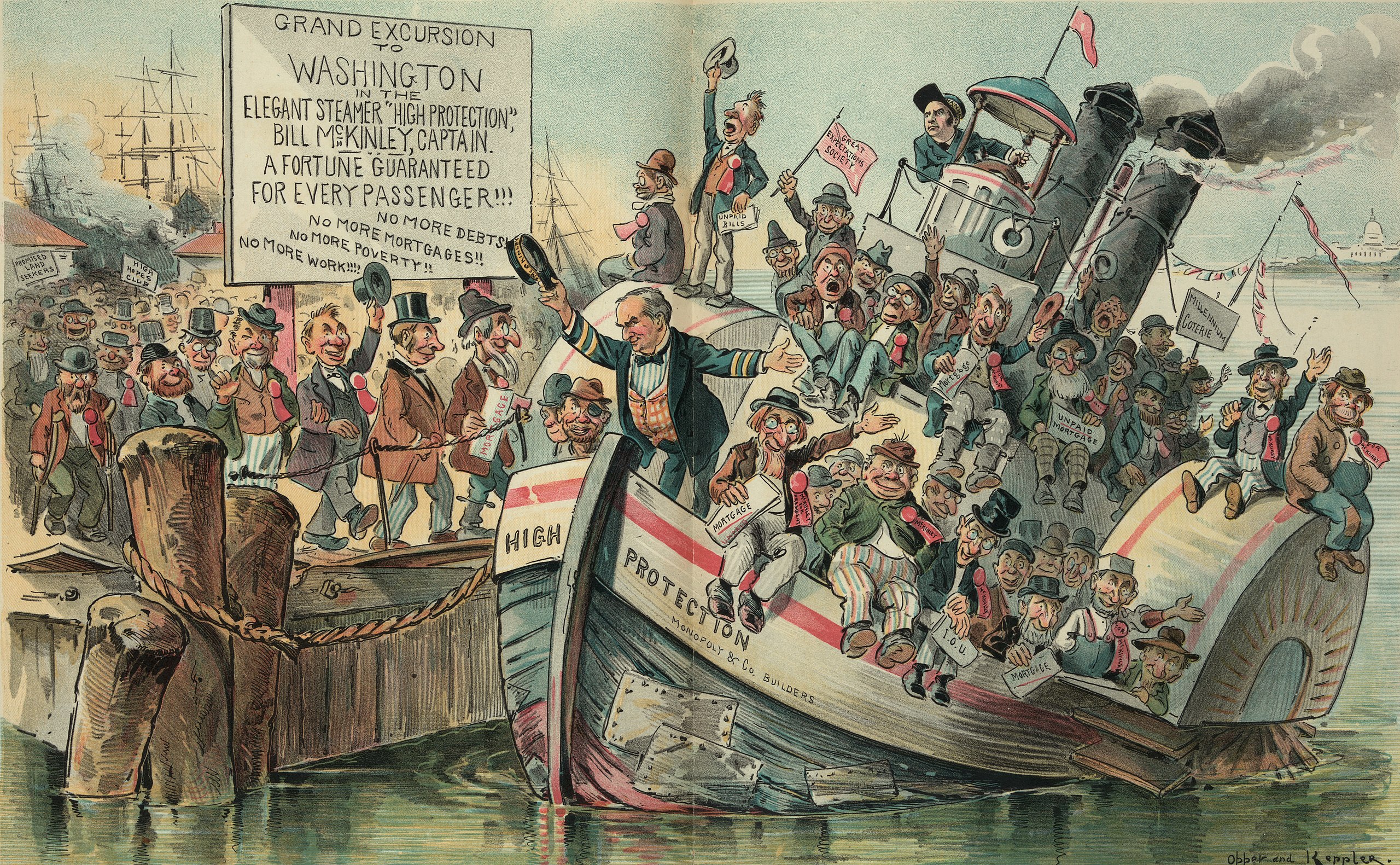

When, during the 19th century, the US emerged as a superpower in its own right, it readily took a page from England’s playbook, setting up tariffs to insulate domestic manufacturing and exercising economic control over foreign territories like Puerto Rico and the Philippines. In his book, Palen includes a political cartoon from 1900 showing then-president William McKinley — the arbiter of the McKinley Tariff, which raised taxes on most imported goods to almost 50% — pushing a giant “prosperity” and “protection” snowball over a snow-covered field labeled “extension of territory.”

Left-wing support for free trade originated in England during the mid-19th century in response to the commercial enslavement of its many colonies. United by a shared anti-imperialist agenda, a diverse coalition of socialists, liberal radicals, feminists, Christians, and peace activists argued that free trade, far from pitting countries against each other in ruthless competition, would allow those same countries to conduct business as equals. Led by liberal English politician Richard Cobden, their influences ranged from writers Mark Twain and Leo Tolstoy to economists J.A. Hobson, Henry George, and, of course, Karl Marx.

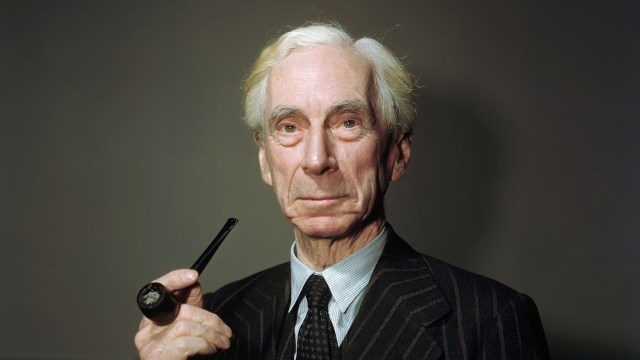

One of the most prominent left-wing advocates of free trade was English journalist Norman Angell, whose 1909 book The Great Illusion argued that an interconnected world economy could help prevent world war. It became a surprise international bestseller.

“Angell was criticized for being too idealistic,” Palen says, “but he understood nationalism and the kind of economic irrationalism that stems from it. His point wasn’t that war had become impossible, but that the economies of the early 20th century had become so interconnected that even the victors of armed conflicts would end up losing.”

Palen stresses that left-wing visions of a free-trade world did not insist on a total lack of regulation, writing they “understood free trade to mean low tariffs for revenue purposes only, rather than their near absence as free trade is commonly thought of today.” Differing from advocates of laissez-faire economics, which insists the invisible hand of the market should be allowed to do its work without interference, Pax Economica adherents argued for the formation of a supranational governing body to help ensure trade between individual countries remained free and fair.

The legacy of free trade

Left-wing support for free trade faced considerable opposition in the West, especially after, in a series of somewhat contradictory events, elements of its underlying philosophy were adopted by the leadership of the British Empire. Chief among the movement’s detractors was the German-American economist and political theorist Friedrich List, who, Palen writes, believed it to be “little more than an ideological smokescreen to hide [its] true intentions: to forever keep Britain the ‘manufacturing power of the world.’” List wasn’t wrong, but he wasn’t right either.

“Britain was the world’s most dominant industrial power,” Palen says, “and it suddenly decides that free trade is not just good for Britain but also for everyone else.” At the same time, he emphasizes the free-trade world dreamed up by imperialists differed from that of the anti-imperialists: “To left-wing ideologues, free trade was supposed to be spread through conversation, not forced on other states as it was in, say, colonial India or Ireland. They were not the same individuals advocating for coercively opening up the Chinese market during the Opium Wars.”

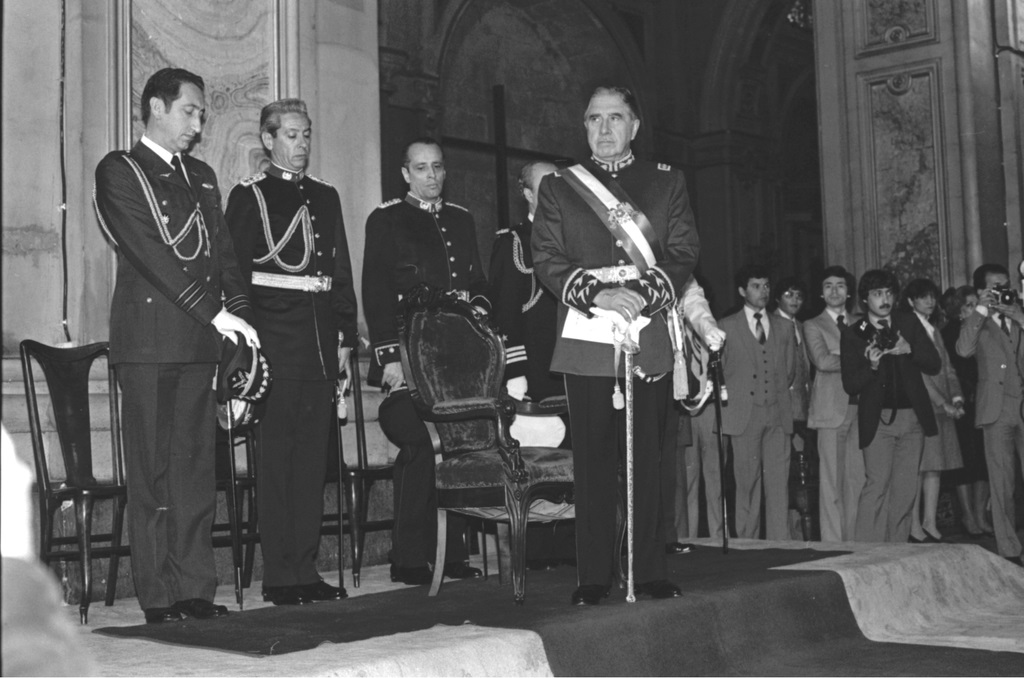

Imperial endorsement of free trade was one of the key factors that led left-wingers to abandon their original program. Another factor, Palen supposes, was the rise of neoliberalism, its growing influence on Western policymaking during the Cold War, and the means with which the United States sought to prevent the spread of communism in other countries. “We saw this, for example, with the backing of Augusto Pinochet in Chile during the 1970s,” Palen says, “and its militant interventionism to protect and enforce open markets, even if it required sacrificing democracy.”

Although left-wing visions of a free-trade world have faded, their influence on the present-day world order endures through institutions like the United Nations and the World Trade Organization — international regulators whose limited but palpable duties transcend the boundaries of states. Traces of the Pax Economica movement also survive in the form of the Fairtrade International label, which signifies wealthy consumers’ willingness to pay more for products they know are produced by people who received fair compensation for their labor, and without damaging the environment.

Return to protectionism

Palen says he wrote Pax Economica not only to highlight free trade’s often overlooked potential for social change but also to expose the dangers of protectionism, which is currently making a strong comeback due to worldwide surges in nationalist sentiments. The coronavirus pandemic, which broke down global supply chains, provided fertile soil for populist leaders and their calls for economic self-sufficiency. What many of their supporters might not realize is that the quest for economic self-sufficiency tends to lead to greater economic inequality — at least, it has in the past.