Here’s What 19th-Century American Cartoonists Thought of Russia

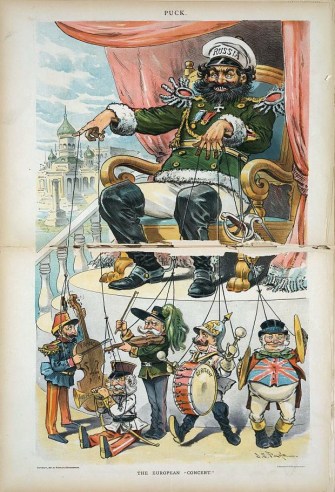

Way before there was Cracked or Mad magazine, there was Puck, a weekly political satire publication out of St. Louis, Missouri. The founder of Puck, Joseph Ferdinand Keppler, published it in English and German, and each issue included several full-color illustrations: on the cover, on the background and on a double-page centerfold. Puck’s images were full of pawky humor that illustrated the political aspects and world line-up before the First World War. By 1884, its success was notable, with a circulation of at least 125,000 copies.

The name Puck was borrowed from the trickster character in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and incarnations of the same character have appeared in tales and myths all over the world: in old Norse, Swedish, Icelandic, Frisian, Welsh, Cornish, Irish and other cultures. In 1871, with the first issue of Puck, the spirit of mischief came to the United States.

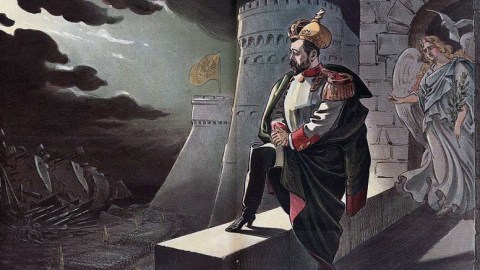

Some of Puck’s 19th century caricatures depicted Tsar Nicholas II, the last emperor of the Russian Empire. His reign ended in the economic and military collapse of one of the foremost great powers of the world.

For most of the 19th century U.S.-Russian relationships were quite rosy due to a largely untold alliance between President Abraham Lincoln and Russian Tsar Alexander II, and that relationship is believed to have been the key to the North winning the U.S. Civil War. However, in the late 19th century, the United States, previously viewed as an agricultural superpower, started to equip itself for a different role, changing the dynamic for good.

Russia’s defeat in the Russo-Japanese War was largely contributed to Wall Street financiers, who loaned Japan the capital to buy U.S.-built warships. The defeat dealt a painful blow to the political prestige of Russian Empire. In 1914, a political controversy with Germany and Austria-Hungary over the independence of the Serbian kingdom dragged Russia into WWI. Like all riches to rags story, Russia’s changing status made great material for political humor and commentary in publications such as Puck.

The first of many tragic events that hit Nicholas II’s reign was the 1896 Khodynka Tragedy, when the festivities following Nicholas II’s coronation led to a human stampede and death of 1,389 spectators. In 1905, a bloody wave of anti-Jewish pogroms reached its peak in Odessa, modern Ukraine, where almost 2,500 Jews were killed and many more wounded. In the same year, an unarmed demonstration that aimed to present a petition to the Tsar was suppressed violently, with hundreds of victims. Due to these events, the last emperor earned the nickname “Nicholas the Bloody”.

Nicholas, his wife Alexandra, and their five children Olga, Tatiana, Maria, Anastasia, and Alexei were killed by the Bolsheviks on 17 July 1918. The family was canonized in 1981 as new martyrs by the Russian Orthodox Church.

The U.S. perception of the political agenda of the late Russian Empire and other major world powers represents itself in Puck magazine’s lithographs. The whole collection is available to view now on Picryl.

A voice from the past / Frank A. Nankivell. 1904

Stop your cruel oppression of the Jews / Flohri. 1903

Kishineff must be paid for – with interest / Keppler. 1904

The European “concert” / J.S. Pughe. 1896

When? / Keppler. 1904