The Mexican Revolution, in the words of those who lived through it

- Despite its international ramifications, the Mexican Revolution is hardly known or studied outside of Mexico.

- This is perhaps because, unlike other revolutions, the Mexican Revolution does not easily lend itself to an easily digestible narrative.

- Consequently, the subject is best studied not through the secondhand accounts of historians but the eyes of the people who lived through it.

Despite technically being the first successful socialist revolution of the 20th century — beating Russia’s Bolshevik uprising by a couple of years — the Mexican Revolution is hardly taught outside of Mexico. This is a shame because the social, political, and economic consequences of this decades-long conflict have rippled out across both space and time.

The outcome of the Mexican Revolution not only affected the development of Middle American countries, but also recontextualized Mexico’s diplomatic ties with the United States. The events of the Mexican Revolution were watched carefully by both Axis and Allied Powers during World War I, with both sides eager to convert this distant country into an ally.

One of the reasons the Mexican Revolution has not become required reading for students across the globe is that it does not lend itself to an easily digestible narrative. Unlike the American, French, or Russian Revolutions, in which the revolutionaries pursued a common goal, the Mexican Revolution is more like a series of loosely connected conflicts fought between many different parties.

These parties were characterized not by their ideologies, but by the personalities of military commanders such as Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata. Consequently, the Mexican Revolution is best understood in its own words; the second-hand accounts of historians — while consistently fascinating and well-written — are not nearly as informative as the primary accounts of those who lived through it.

Emiliano Zapata and the Plan de Ayala

The Mexican Revolution began with Porfirio Díaz, who had been elected president under the false premise that he would — once his term came to an end — allow free elections. Aside from dismantling the country’s democratic foundations, Díaz also handed over land and resources to American investors in exchange for money and protection.

Although Mexico was a sovereign entity on paper, little had changed since it acquired independence from its Spanish colonizers. While each revolutionary faction had its own reasons for rebelling against the Díaz regime, many shared in their desire to transfer ownership of Mexico’s resources from foreign powers into the hands of the country’s own alienated residents.

Few revolutionary leaders pursued this goal as fervently as Emiliano Zapata. Born and raised in the small agricultural community of Morelos, Zapata had spent much of his youth working on farmland that didn’t belong to him. In his 1911 manifesto, the Plan de Ayala, he promised to keep fighting in the Revolution until Morelos was granted autonomy from Mexico’s federal government.

The Plan also served as a formal denunciation of Francisco Madero, a revolutionary whom Zapata helped overthrow Díaz in exchange for landownership, but who ultimately refused to fulfill his end of the bargain. Zapata declared Madero “a traitor to the principles that enabled him to climb to power” who had “crushed with fire and blood those Mexicans who seek liberties” so he could pacify Díaz’s trading partners.

Anthony Quinn and A Soldier’s Life

Today, the Mexican Revolution is perhaps best known as the first military conflict that saw the large-scale conscription of combat-able women. These women, colloquially known as soldaderas, mostly served in the army of one revolutionary leader: Pancho Villa. This elite cavalry force was an indispensable element of Villa’s organization, turning many a tide in the revolutionary’s favor.

But while the dire circumstances of the revolution allowed some women to assume roles society would have previously considered unacceptable, they more often than not served to enforce rather than break with traditional stereotypes. While some soldaderas fought in battle, the vast majority of them worked as cooks, cleaners, and bedmates.

The daily life of such soldaderas is described in the autobiography of Academy Award-winning actor Anthony Quinn. Quinn, who was conceived during the Revolution, recounts the story of how his father, a foot soldier, asked his mother to become his soldadera. Quinn’s father, single at the time of conscription, needed someone to prepare food and keep him company at night.

“Thank God my mother had taught me how to cook,” Quinn’s mother had thought to herself, “so I didn’t disgrace myself among the other women.” Unfortunately, she had plenty of other things to worry about: “I would have to go to sleep near this boy whom I hardly knew, this boy who had never said pretty things to me and who just took me for granted.”

Revolution: from battlefield to countryside

Authentic descriptions of combat experience are hard to come by, as soldiers were so busy trying to survive that they had little time to record their thoughts and feelings. Fortunately, revolutionary armies were often accompanied by journalists and filmmakers who risked their lives trying to capture the events unfolding around the nation.

One such journalists was John Reed, who rode into battle alongside Villa and wrote the following description of it: “The shooting never ceased, but seemed to be subdued to a subordinate place in a fantastic and disordered world. Up the track in the morning light straggled a river of wounded men, shattered, bleeding, bound up in rotting and bloody bandages, inconceivably weary.”

In every war, the people who refuse or are unable to fight far outnumber those that do. The experience of these pacificos, or noncombatants, make up an important part of the Revolution’s historical mosaic. Over the course of the conflict, the pacificos had to fight off famine and invasion. Without any able-bodied men around, they were often unable to defend themselves against bandits or plundering soldiers.

Many pacificos struggled getting used to the economic unpredictability and lawless violence that came to characterize the once peaceful routines of daily life. Well-to-do families lived in fear of marauding armies, which — when left unsupervised — often plundered nearby towns for food and valuable goods. If the owners of those goods attempted to resist, they could be beaten or shot down.

The enduring relevance of the Mexican Revolution

Another reason why the Mexican Revolution is rarely taught is that scholars have yet to decide on a proper way to teach it. There is, for instance, little to no consensus on when the conflict began and when it ended. Some history books choose to start at 1910, the year when Díaz was deposed and the power struggle began. Others argue the roots of the revolution dig back to the colonial era.

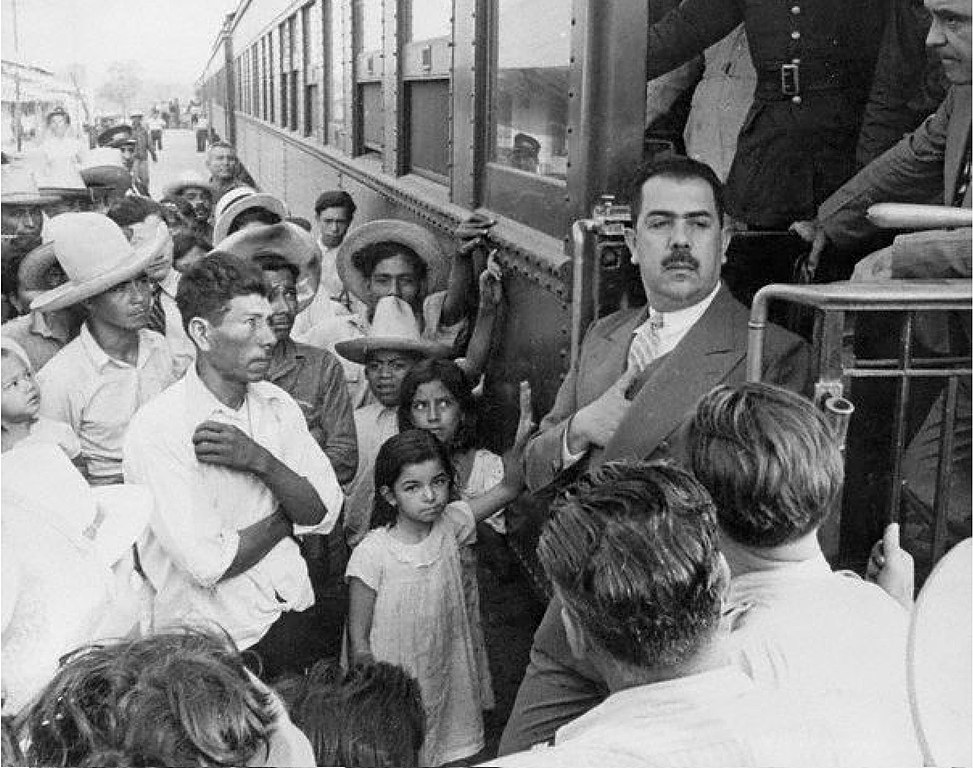

Debate on when the revolution ended has proven even fiercer. Some turn to 1924, the year large-scale military conflicts ceased and Elías Calles coordinated a peaceful albeit disingenuous transfer of presidential power. Others point to the 1934 election of his successor Lázaro Cárdenas, who greatly reduced governmental corruption and nationalized Mexico’s petroleum industry.

Others argue the Revolution never ended, and that Mexico is still woefully dependent on its relationship with foreign powers, stuck in a perpetual state of becoming. Regardless of the camp you reside in, though, the Mexican Revolution is a fascinating time period in history to study, being a reflection of both global movements and uniquely Mexican unrest at the same time.

In the preface of his book, The Mexican Revolution: A Brief History with Documents, historian Mark Wasserman states that the sequence of events we now refer to as the Mexican Revolution are unimaginably complex, involving people from all walks of life. It is only through the study of their direct accounts that a complete picture of this time period can be produced.