The strange, possibly German origin of UFOs

- Nazi Germany was among the first countries in the world to develop an interest in flying saucers for their strategic significance.

- An airport hangar in Prague was turned into a research facility where engineers struggled to get their creations off the ground.

- Though they probably did not succeed, their interest in the subject has given UFOs a sense of mystique they have kept to this day.

One of the strangest photographs from World War II depicts a barely discernible saucer-shaped object flying high above Prague’ airport. It was allegedly taken by the inventor Joseph Epp, called in to help Nazi engineers get their latest creation off the ground. By the time Epp got to the airport, the device was already up and running, soaring in ways that, though familiar to us now thanks to sci-fi movies, must have surely looked a little alien back then.

Rumors about flying saucers did not emerge until after the war had ended, and there is a surprising reason for that. During the early 1940s, it appears that the Third Reich was putting considerable time, energy, and resources into the development of a new type of aircraft, one that — thanks in part to specialized rotors — would be able to fly not just horizontally like most other planes but vertically and even diagonally as well.

These kinds of vehicles, if operational, held tremendous potential in the eyes of the German military. Their maneuverability made them promising weapons of aerial warfare. Their ability to move up as well as down with ease meant that they could land and lift off without requiring a mile-long runway. Pilots might learn how to use them to get out of tight spots, chase enemies, and of course reach places that traditional aircraft could never go.

German engineers had a reputation for creating machinery that was considered way ahead of its time, and the prospect of creating the world’s first, fully functional “UFOs” did not seem to intimidate them. Evidence, ranging from the aforementioned photograph to administrative records, suggests the Third Reich may have come close to realizing this outlandish vision. In the end, however, Nazi UFOs are just like any other: shrouded in mystery and misinformation.

The first flying saucers

Epp completed his first blueprint for a flying disc as early as 1938, after witnessing a test flight for the Focke-Wulf Fw 61. This vehicle, a prototype of the modern helicopter, relied on rotors located at the ends of its wings to lift itself off the ground. In his design, Epp moved the rotors underneath the airframe to allow for greater flexibility. He also changed the vehicle’s shape to something that was more disc-like. This, he thought, would make it more stable.

Epp then used his blueprint to build a number of small, proof-of-concept models that, when submitted for review in 1941, quickly garnered attention among members of Berlin’s Ministry of Aviation. Not long after, a facility was opened near Prague airport in Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia where Epp — alongside other German and Italian engineers who came up with the same concept — spent the next few years trying to turn his idea into reality.

One of the prototypes they allegedly put together was the “Flugkreisel,” created by engineer Rudolf Schriever. It was both similar to and different from Epp’s UFOs, with paddles extending from a central, circular control cabin, reinforced with vertical and horizontal propulsion jets. Once finished, the vehicle had a diameter of 42 feet and weighed more than three tons. In a post-war transcript, a Nazi officer called Otto Lange claims to have served as its test pilot.

It is unclear how much progress was actually made at the airport. When Soviet troops invaded Czechoslovakia in April 1945, the engineers were forced to destroy all the progress they had made. Every single prototype was destroyed, and only a few documents could be saved during the evacuation. These, along with testimony from the engineers involved, are the only traces that remain of this top-secret operation.

Postwar research endeavors

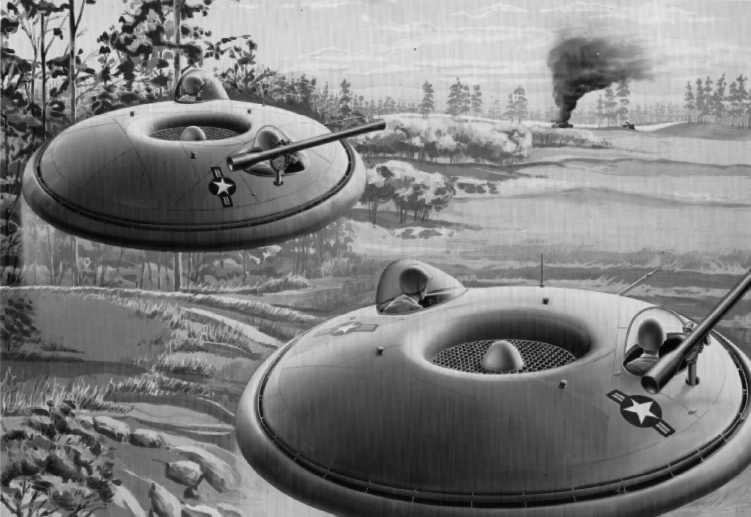

Scientific interest in flying saucers briefly waned after Hitler’s defeat but resurged when tensions between superpowers rose during the Cold War. Once nuclear holocaust turned from a harmless thought experiment into a very real and immediate threat, a new generation of engineers turned toward disc-shaped aircraft. These, they thought, could prove useful in a future where airports were giant targets and populations needed to be evacuated quickly and efficiently.

In a video on the subject, World War II historian Mark Felton wonders if the American research and development programs from the 1950s and 1960s ever enlisted help from German engineers. The designs from the Third Reich were, after all, “far in advance of anything the Americans were coming up with,” and some of the prototypes, like John Frost’s Avro Canada CF-100, looked an awful lot like the flying discs that reportedly had been built in Prague.

If any German engineers had been asked to join, Epp was not one of them. Not that he didn’t want to participate. On the contrary, the inventor reached out to the American government on several occasions offering his services. When they refused, Epp tried his luck with the Soviets. When they refused as well, he tried to patent his designs and waited more than ten years before finally getting one. Why it took so long for the authorities to get back to him, no one knows.

Schriever had a different experience if he can be believed. Working as a truck driver for U.S. occupation authorities in post-war Germany, he claims he was approached by a group of men belonging to an unidentified organization or government. They asked him if he could help them develop a disc as he had done in Prague, but Schriever refused. Shortly after, his workshop was burglarized and any documents relating to this period had disappeared.

The truth about Nazi UFOs

Unlike their German counterparts, American engineers heavily documented their attempts at making a functional flying saucer. Video footage of test models show a heavy, rotund, aluminum-clad vehicle floating in midair like an oversized hovercraft. No matter how hard the pilot tries to take flight, the engines won’t budge. When, some time later, no progress had been made in this department, the project was dismantled and forgotten.

In light of such a terrible disappointment, one wonders whether the accounts of Epp and Schriever — featured prominently in Nazi newspapers back in the day — can actually be trusted. If America’s most promising specimen struggled to maintain an altitude of ten inches, are we really to believe that decades earlier German engineers had created a saucer capable of reaching the same heights as a traditional aircraft?

Felton thinks not. “There is one obvious point we must consider,” he states, “that Epp, Schriever, and all the other engineers and pilots who spoke about Nazi flying saucer research were lying. The entire program is a fiction that has been turned into a believable story by authors and documentary filmmakers, and that flying disc research only really got underway in the fifties in Canada and the United States, and disappeared in the 1960s as engineers couldn’t make them work.”

While it is true that the connection between UFOs and Nazi engineering often seems as dubious and conspiratorial as UFOs themselves, there can be no denying that the Third Reich was among the first countries in the world to develop an interest in the flying saucers. Though they may have never gotten one off the ground — and evidence to the contrary may well be nothing but propaganda — their efforts imparted the saucer with a sense of mystique it has kept to this day.