The forgotten voyagers of ancient Greece, China, and Scandinavia

- Long before Columbus reached the Americas, brave individuals in classical antiquity were exploring the unknown regions of their own world.

- Roman navigators and Irish saints sailed farther than any of their contemporaries had dared to go, returning home with stories of sea monsters and demons.

- Historians read these stories with a pinch of salt, keeping the explorers’ limited knowledge and outdated worldviews in mind.

We tend to associate the word “explorers” with people like Christopher Columbus, Ferdinand Magellan, and other seafarers who lived during the period when Europe’s kingdoms were organizing the first expeditions to the New World. But brave individuals have been exploring the uncharted regions of their worlds long before 1492, changing their own communities in the process.

Historians are not just interested in the locations that ancient voyagers reached, but also in the stories they brought home with them. These tales rarely reflected reality — and for good reason: Like modern-day travelers, ancient voyagers made sense of their surroundings using their own, often outdated, worldviews.

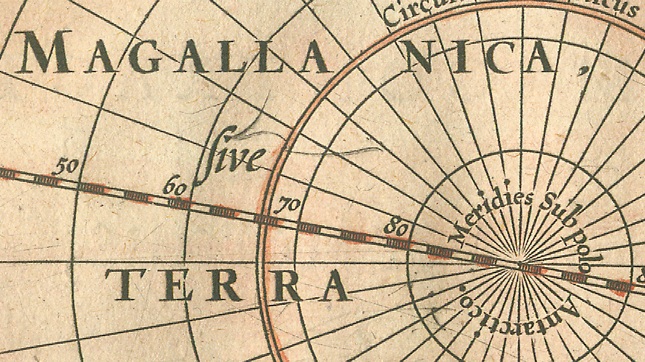

Look, for instance, at this map of the known world made by the Alexandrian mathematician and geographer Ptolemy around 150 AD. Turkey, Greece, Italy, Spain, and even parts of Scandinavia are clearly recognizable. So is the vast expanse of Asia, which in Ptolemy’s time had already been partially explored through trade with India.

More enigmatic is the massive shape replacing Africa. The placement of this unruly landmass is based not on measurements but induction; Ptolemy’s rudimentary cosmology necessitated that the as of yet unexplored continent of Africa had to be of a certain size so as to balance the weight of Asia and Europe. He was right, but for the wrong reasons.

Exploration in classical antiquity

The ancient Greeks were skilled voyagers. Their civilization was scattered across hundreds of tiny islands, from Crete to Rhodes. Through trade and exploration, the Greeks made contact with places as nearby as the Levant and Persia, and as distant as China, England, and Scandinavia, the latter of which was explored by the astronomer Pytheas around 325 BC.

Explorations in classical antiquity took place for many different reasons, including the desire for knowledge. Posidonius, a philosopher from the Roman Republic, observed that the tides in Hispania were much higher than those of the Mediterranean, leading him to suggest that ebb and flow were somehow connected to the orbit of the moon, a conclusion he might not have reached had he stayed behind in his native Syria.

Most ancient expeditions, however, were undertaken in the hope of finding trade routes that gave access to the treasures of foreign countries. According to a text called the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, the Greek navigator Hippalus, who lived in the 1st century BC, discovered a new and faster route from the Red Sea to southern India by sailing through the Indian Ocean instead of sticking to the shoreline.

Particularly interesting is the case of the Carthagian navigator Himlico, who lived sometime during the late 6th or early 5th century BC and is said to have been the first person from the Mediterranean to have reached the northern shores of Europe. Accounts of his travels, quoted by many a Roman writer, are filled to the brim with descriptions of sea monsters, which historians suspect were included to dissuade rivals from sailing down Carthage’s new trade routes.

The creation of the Silk Road

While Mediterranean explorers were busy navigating the edges of Europe, Chinese voyagers ventured into central and southeast Asia. Chief among these voyagers was Zhang Qian. Qian, who died around 114 BC, was a diplomat who, on behalf of the Han Emperor, traveled west to create the infrastructure for what would eventually become known as the Silk Road.

Zhang Qian’s accounts were compiled by Sima Qian in the 1st century BC in his Records of the Great Historian. Reading these chronicles allows us to look at ancient history from a different perspective. Long-gone empires, with their foreign traditions and current events, are reconstructed from the perspective of a Chinese traveler who lived during the Han dynasty.

Most of the cultures visited by Zhang Qian no longer exist today. These included the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, whose chiefs were being subjected by the Yuezhi, a nomadic tribe whose history began in northwestern China. Zhang Qian found Greco-Bactrian influence enduring in the country of Daxia. Located in modern-day Afghanistan, Daxia was famous for breeding powerful horses that the Han dynasty would later seek to obtain through war.

Southeast of Daxia lay a civilization that Sima Qian refers to as Shendu, from the Sanskrit word for the Indus river, “Sindhu.” Shendu was the largest of Indo-Greek kingdoms on the Indian peninsula. “The people,” Sima Qian writes, “cultivate the land and live much like the people of Daxia. The region is said to be hot and damp. The inhabitants ride elephants when they go in battle.”

Who settled Iceland?

History buffs like to point out that Norse Vikings, not Columbus and crew, were the first Europeans to reach American shores. But before the Vikings entered the western hemisphere, they were exploring a little closer to home. After colonizing parts of Russia, their sights were set on Britain, Ireland, and Iceland.

According to the Icelandic Book of Settlements, a medieval text, Iceland was first settled by the Norseman Ingólfr Arnarson, also known as Bjǫrnólfsson, who built his homestead in 874 and named it Reykjavík. However, medieval writers as well as archeological excavations suggest the island was populated earlier, possibly by Irish monks who left after Bjǫrnólfsson’s arrival.

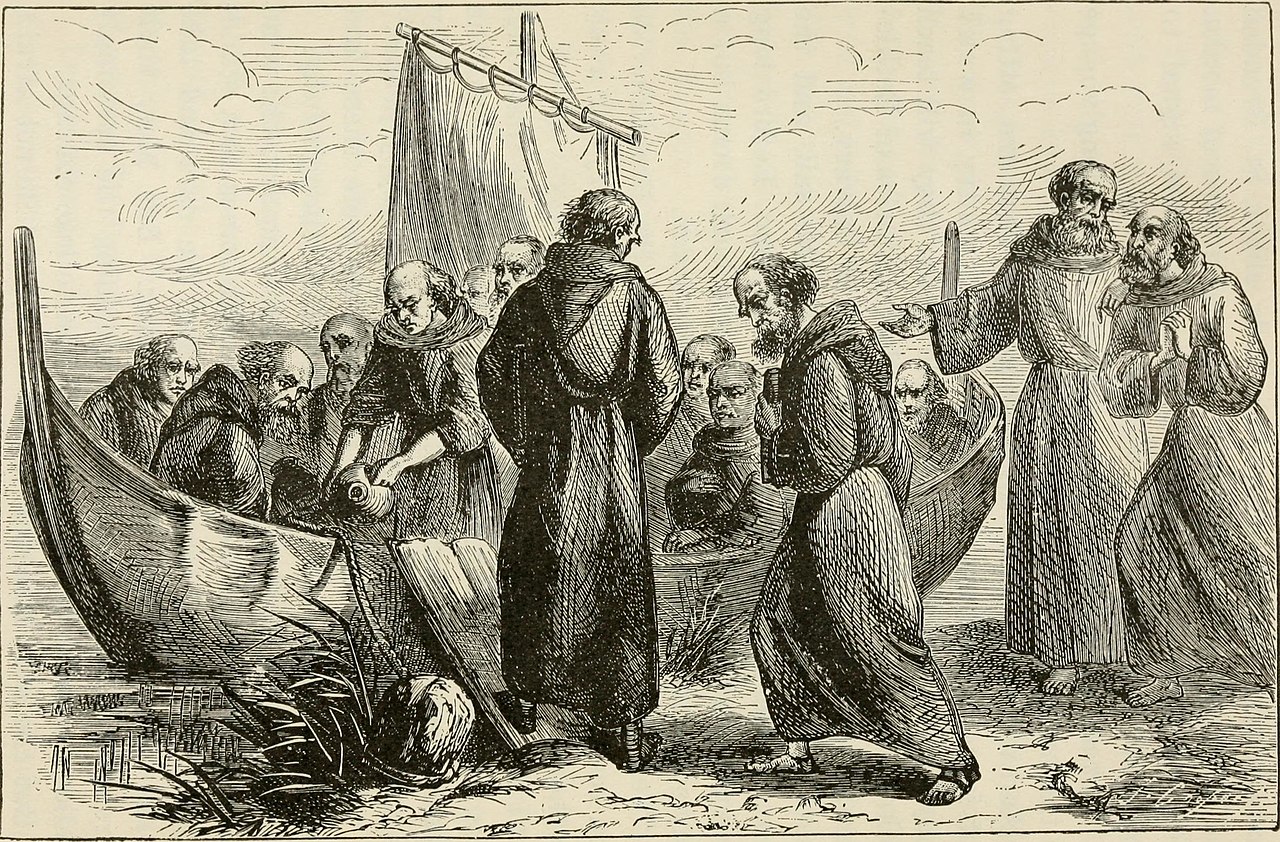

One of these monks may well have been St. Brendan. Also known as Brendan the Navigator, this Fenit-born saint is said to have set out on the Atlantic Ocean in the company of 16 monks to search for the Garden of Eden, heaven on Earth. In reality, though, Brendan probably traveled to convert pagan communities to Christianity.

Irish stories about Brendan’s voyage read more like scriptures than historical accounts. They are packed to the brim with fantasy and religious symbolism, making it difficult for scholars to use them as evidence. In one story, Brendan claims to have encountered the gates of hell, a place where “great demons threw down lumps of fiery slag from an island with rivers of gold fire.” In reality, he may have witnessed volcanic activity while sailing around Iceland.