Why you should always lie to election pollsters

- Polling has been criticized for creating bandwagon effects, undermining the role of campaigns, and discouraging voter participation.

- As the accuracy of predictive technologies improves, it remains an open question whether they will exacerbate these effects.

- We must not let polls become self-fulfilling prophecies.

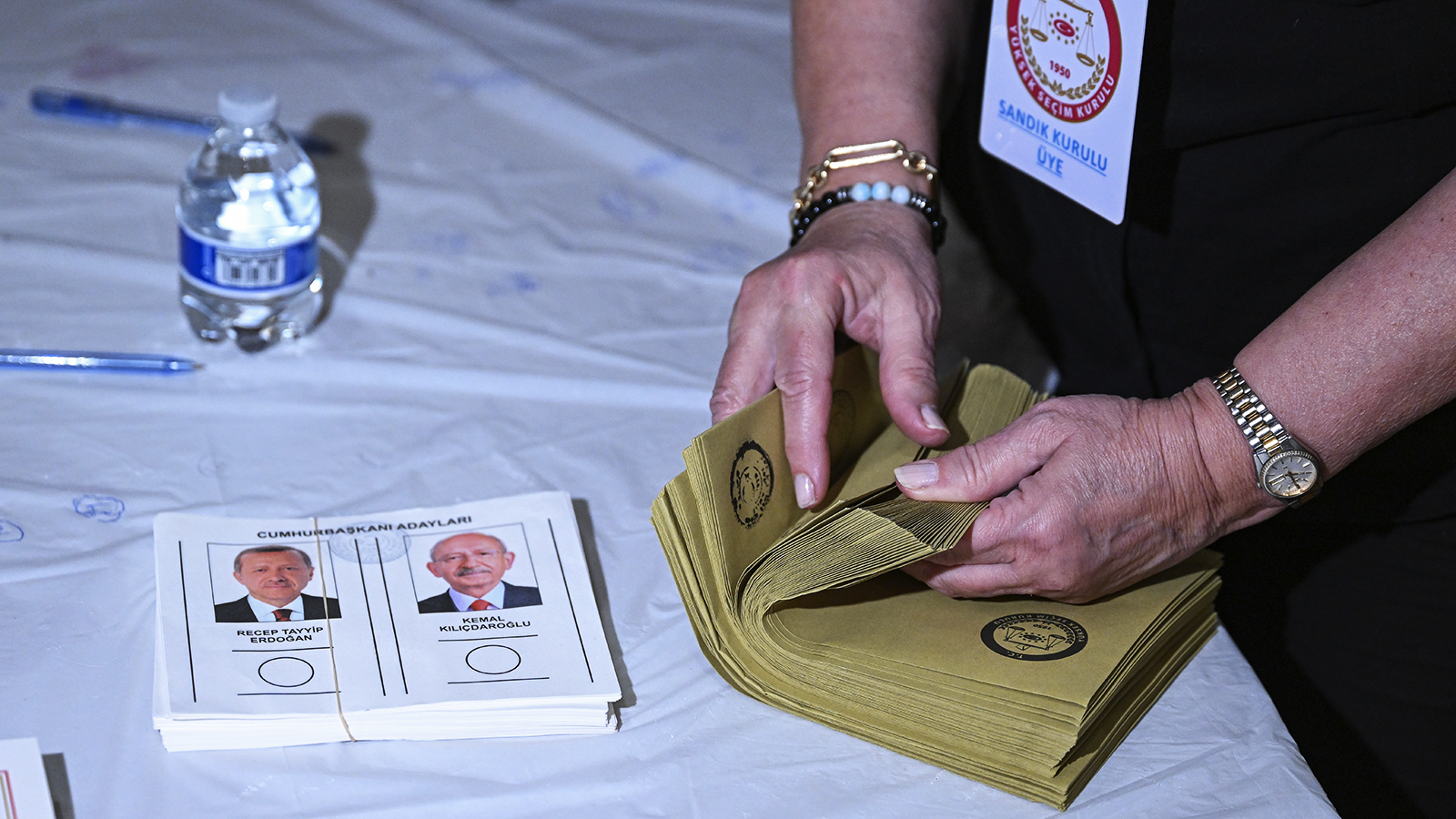

Some critics have long viewed polling as an attack on democracy, potentially poisoning that source of democratic legitimacy, voting. In 1996, a journalist named Daniel S. Greenberg wrote a column in The Baltimore Sun that effectively summed up his problem with what he called “the quadrennial plague of presidential election polling.” Greenberg was hardly a crank. He was a veteran journalist who had helped transform science reporting at Science, the journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and who published the Science & Government Report. He knew of polling’s prediction failures, but that wasn’t really what bothered him about what he characterized as an “infestation of polling moving deeper into the electoral system.”

Greenberg’s critique focused on polling results that “are easily confused with political reality, producing bandwagon effects, heartening the leaders and disheartening the laggards.” Polls can make it seem as if an election is over long before Election Day, undermining “the historic role of campaigns… to educate the voters about candidates and issues.” Polling encourages candidates to alter their personae or issues based on “voters’ anxieties and fears,” leading to governance by polling. Worst of all, in Greenberg’s view, were deceptive push polls, which under the guise of a conventional poll try to influence voters through deceptive questions, spreading “political poison.” (Push polls were the primitive predecessors to Cambridge Analytica’s efforts.)

How can citizens protect their rights against this insidious force? Easily, wrote Greenberg: Refuse to reply or lie. After all, small events can create large errors, which could bring polling down.

A few years after Greenberg’s jeremiad, Kenneth F. Warren, a professional pollster, spent 317 pages of his book In Defense of Public Opinion Polling (2001) reviewing and refuting the case against the practice. His first chapter went straight to the problem: “Why Americans Hate Polls.” He broke the reasons down into six capacious buckets: polls are un-American; polls are illegal, if not unconstitutional; polls are undemocratic; polls invade our privacy; polls are flawed and inaccurate; and polls are (paradoxically) very accurate and intimidating.

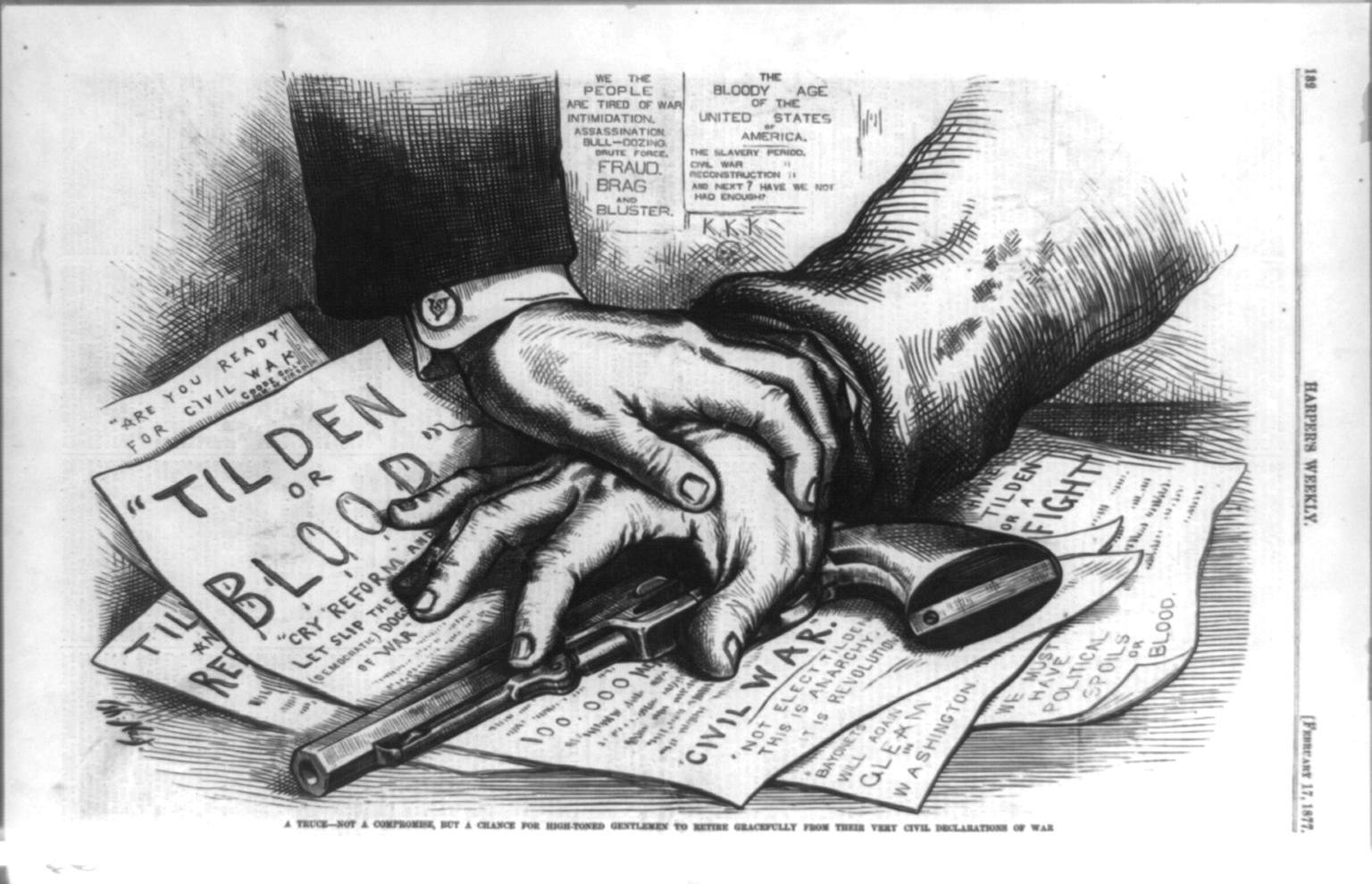

That was two decades ago, an age before social media, smartphones, mainstream conspiracy theories, and Cambridge Analytica’s psychometric techniques. Warren’s sunny defense of polling, although comprehensive, showed no appreciation for the darker currents already running through modern American society. (Many of these currents, such as paranoia and conspiracies, have, of course, long been part of U.S. history.) In fact, the anxieties provoked by polling are in their own way predictive. Moreover, many of those fears emerged in more potent form with the new technologies and techniques.

Polls can make it seem as if an election is over long before Election Day.

Igor Tulchinsky and Christopher E. Mason

To be successful, prediction technologies at a certain point run into questions over privacy. They require data unique to individuals, such as their genome or (far dicier and less developed) the bubbling contents of their minds and personalities — what the late 19th-century psychologist William James called “the stream of consciousness.” Prediction of nature is the subject of that awe-inspiring endeavor known as modern science. We want to know what the weather will be, how the pandemic will spread, or when the earthquake will occur. We may doubt that prediction is possible or may believe that we, like early proponents of smallpox inoculations, are engaged in a rebellion against God’s will and so resist the advice of science.

Prediction in humans, however, cuts far more deeply and is far more difficult. To achieve a degree of predictive precision or even to develop a better quantitative sense of uncertainty and risk requires an understanding of human impulses and dynamics.

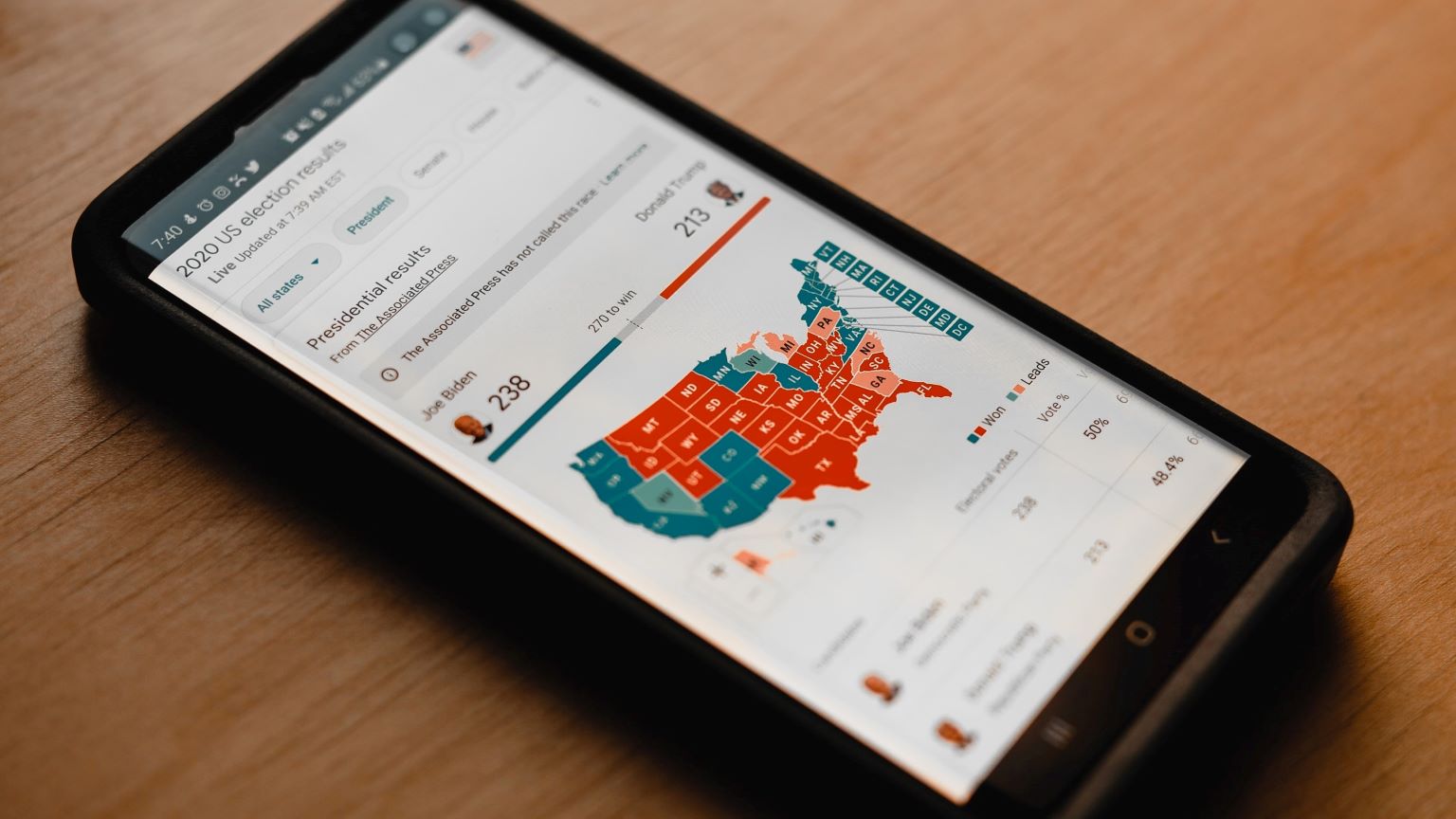

Imagine a set of algorithmic tools, diverse and ample proxy data, and powerful machine-learning programs focused not on manipulation but on learning how to more accurately predict elections. The system would target such key questions as who is likely to vote, how big the undecided pool is, and what deeper psychological factors determine how individuals make decisions. The use of techniques aimed at manipulating voters would be banned. Imagine that over time the failures punctuating the history of scientific polling will fade away, the error rates will shrink, and public confidence will rise. In effect, as predictive capacity grows, the risk of a prediction failing will steadily decline until it approaches zero.

Would that be good or bad from a democratic perspective, meaning not that the “best” candidate necessarily will win an election but that the polls will accurately mirror the sentiments of voters? How would potential voters react to a deep belief that the pre-election polls are correct? Except in elections that look extremely close, why would they bother to ponder public issues or vote, except as a sort of civic gesture or a comforting rite? (Today, there’s an analogous situation in markets, where increasing numbers of investors opt to buy indices without applying any effort at research or analysis.)

This is a complaint long made about conventional polls — that they can make or break candidates needlessly or, more acutely, that calling elections can deter people from voting in states whose booths are still open. If the polls become extremely accurate, will millions simply not bother to vote, believing that the polls aren’t wrong? Falling voter participation tends to introduce volatility in the results, like a stock with a small float of shares or like primaries or runoff elections. And what about governing? If prediction gets so precise, why not govern by poll, going directly to the people and getting rid of the leeway traditionally afforded to elected lawmakers to make decisions in a republic governed by representation?

Politics and governance are enterprises engaged in coping with an uncertain future; polls are flickering flashlights in the dark.

Igor Tulchinsky and Christopher E. Mason

Those questions take us to a very different world, a long way from the one the U.S. Founding Fathers envisioned — in fact, to a democratic reality that they feared. Politics and governance are enterprises engaged in coping with an uncertain future; polls are flickering flashlights in the dark. Columnist and public intellectual Walter Lippmann was essentially right about a democratic citizenry uninformed on many important matters, in particular economics, science, and foreign policy. But he may have misjudged the potency of his solution, which was to find experts to tackle issues that in some cases might have no clear-cut solutions, that run roughshod over popular conceptions of fair play or morality, or that require sacrifices by voters. (Think of the difficulties of doing anything about a relatively straightforward prediction problem such as climate change.)

In a democracy, politics is ambivalent about prediction: on the one hand worshiping market sages or political commentators who wear the mantle of prescience (until they’re wrong enough times) but on the other resisting limitations on free will and incursions into the individual’s autonomy. Prediction that eliminates risk and uncertainty may require the kind of personal-data gathering that can feel like a transgression (and in a few cases already requires payment). Moreover, the line between prediction and control — no access to data, no insurance — is often a contested one.

All this raises fewer questions about whether enhanced prediction is possible than about the effects of the backlash to it. There is no doubt that improving prediction promises enormous benefits in any number of areas, shrinking risks that have hung over humanity since prehistory. But it also brings with it new problems and risks.

The drive toward better prediction clearly increases the appetite for more and better data, leading to recent critiques such as Age of Surveillance Capitalism (2019) by Harvard Business School’s Shoshana Zuboff, who argued in a New York Times commentary in 2021 that an “epistemic coup” has been perpetrated by the big tech companies, particularly with respect to the kind of data that drive many advanced prediction technologies. Zuboff believes that if democracy is going to survive, we must regain control over our personal data — “over the right to know our lives.”

Her solution to the “coup” is for democracies to take back commercial control of data and resist the encroachments of technological surveillance, much as Daniel Greenberg advised folks weary of pollsters telling them what to think not to respond to them, or to lie. Zuboff’s somewhat apocalyptic scenario is an illustration of the kind of feedback loops that can be set up by transformations as profound as the enhanced power of prediction.