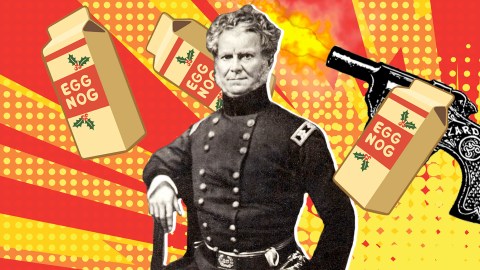

The boozy and violent story behind America’s Eggnog Riot

Big Think

- In 1826, Americans loved to drink, and the young cadets at West Point Academy were no exception.

- After being forbidden from imbibing everyone’s favorite egg-based holiday beverage, West Point cadets would go on to start a riot that lasted into the early hours of Christmas morning.

- The story behind the Eggnog Riot both offers a glimpse into life in 1826 and the history behind how West Point became the disciplined institution it is today.

Americans used to really enjoy a stiff drink or five. Today, the average American drinks a little over two gallons of pure alcohol a year, but in 1830, that number was 7.1 gallons. It makes sense: Clean drinking water was hard to find, the dangers of alcohol were less understood, and it was just common practice to toss a few back throughout the day.

Unfortunately, maintaining a near-constant buzz has a tendency to limit your prospects in life. In 1826, Colonel Sylvanus Thayer was tasked with molding the nation’s top military minds at West Point Academy, but he had a problem: the academy’s cadets were drunks.

The student body in 1826 was a particularly bad bunch. Among them was Jefferson Davis, who’d later go on to become the president of the Confederacy. Before this, though, Davis drunkenly stumbled into a 60-foot-deep ravine, and was the first cadet to be arrested for visiting the local tavern.

He was arrested because Thayer was determined to whip some discipline into the fledgling academy and its cadets. Thayer is known as “the father of West Point” because of the many reforms he made, such as raising admissions standards, introducing engineering as a key subject, and outlawing the consumption of alcohol. Before 1826, though, students were permitted to drink on the fourth of July and Christmas; this would be the first year that Thayer forbade drinking even on these special occasions, with disastrous consequences.

Sylvanus Thayer, who would go on to be known as “the father of West Point.”

Wikimedia Commons

Smuggling whiskey

Come Christmas Eve, several boozehound cadets hatched a plan. Traditionally, they would drink eggnog on Christmas Eve. The creamy beverage was a luxury in Europe, but because the United States had so many farmers, it was easy to come by the requisite eggs and milk. Normally, the drink was spiked with rum (unless you were George Washington, whose private recipe called for brandy, whiskey, rum, and sherry). This year, there’d be eggnog, but no liquor.

This wouldn’t do, obviously. So, with the enthusiastic support of Davis, a number of cadets set out across the Hudson river to go find some precious brown stuff to spike their nog with.

This was risky. Davis had already been arrested for drinking, and although the cadets regularly frequented the nearby taverns, getting caught would have been disastrous. After nearly starting a fight in one tavern over the cost of the liquor, the cadets went to another, where they procured four gallons of whiskey. When crossing back across the Hudson, they were stopped by a West Point security guard. Luckily, a 35-cent bribe was enough for him to look the other way.

Things get violent

With all the necessary ingredients in place, the cadets could begin their furtive partying. But, like any who’s ever lived next door to college students can attest, drunk kids don’t stay quiet for long. At four in the morning, Captain Allen Hitchcock—who was charged with keeping watch over the cadets that night—awoke to the sound of singing above him.

He ran up, ordered the crowd of drunk men to go back to their beds before he heard more partying in a nearby room. The cadets in the next room had somehow gotten wind that Hitchcock was coming, so they used their wits and tactically hid themselves under their blankets, which Hitchcock immediately noticed. Another cadet decided to use his hat to cover his face. Hitchcock furiously demanded the student reveal himself and was ignored. Heated words were exchanged.

When Hitchcock left to investigate the sounds of another party, one of the men shouted “Get your dirks and bayonets… and pistols if you have them. Before this night is over, Hitchcock will be dead!” You can always tell that a party’s mood has turned sour when folks start calling for somebody’s death.

Captain Ethan Allen Hitchcock. Of course this man would break up young people having a party.

Wikimedia Commons

Davis, who was absolutely sloshed at this point, burst into a room filled with other partiers and shouted, “Put away the grog boys! Captain Hitchcock’s coming!” Captain Hitchcock was directly behind him and ordered Davis to return to his room. Davis obeyed, which would later save him from being court-martialed.

Hitchcock found himself playing an increasingly violent game of whack-a-mole. Whenever one group of cadets were ordered back to their bunks, he’d hear another group singing or smashing windows and plates. He went to break up another party, only to find the door barricaded. After he burst through, one cadet fired a pistol at the captain, but his shot was (fortunately) interrupted by another cadet who bumped into the would-be murderer. The bullet buried itself harmlessly in the door jamb. It’s not clear whether this was an intentional act or whether the man had just drunkenly stumbled into the first cadet.

Meanwhile, Lieutenant William Thorton—also tasked with chaperoning the cadets—was meeting equal resistance. One cadet brandished a sword at him, while another whacked him over the head with a chunk of wood. The cadets weren’t calming down or dispersing; the officers decided to call for backup. Hitchcock asked a cadet relief sentinel to “bring the ‘com here,” but the drunk rioters misheard this as “bombardiers,” a nickname given to West Point’s artillery men.

The artillery men and cadets were bitter rivals, and the thought of being subdued by their artillery men enraged the cadets. Windows were smashed, banisters were ripped away from staircases, plates were shattered and thrown about—but the night was coming to an end, and the cadets were sobering up.

Up to 90 cadets out of the academy’s 260 were involved in the Eggnog Riot. It wouldn’t do to indict over a third of the young Academy’s class, so Thayer chose only to punish the worst offenders. Nineteen cadets were expelled, but Davis and his future general Robert E. Lee were not among them.

Depending on your point of view, this story can be a cautionary tale about the dangers of over-imbibing or the dangers of excessive discipline. Regardless, I hope you raise a glass (just one) of some eggnog this holiday season in remembrance of West Point’s great Eggnog Riot.