A philosopher’s case against death

The idea is intuitive: It is good to be alive; it is bad to die. Yet many, even most, resist this idea, and not just because they believe in an afterlife. Some of the resistance comes from the worries about what would happen to the world if we lived much longer: Overpopulation! Stagnation! Social security and pension crises! These are reasonable concerns: Something that appears to be good for the individual can have such bad effects for society that in the end it is good for no one. But more commonly, people simply appear to accept that death comes after a full life; they do not object to death, only untimely death.

Writer David Ewing Duncan traveled the United States giving talks on biotechnology and life extension. At each venue, he asked the audience if they would want to live 80 years, 120 years, 150 years, or forever. People were allowed to imagine breakthroughs in antiaging medicine. Out of 30,000 people, around 60 percent responded by saying 80 years, 30 percent said 120 years, nearly 10 percent said 150 years, and less than 1 percent said forever. His results were similar to those of a 2013 survey conducted by the Pew Research Center about Americans’ opinions on death. When asked how long they would want to live, 69 percent gave a number between 78 and 100. The average ideal life span turned out to be about 90. Only 8 percent said that they would want to live beyond 100, and only 4 percent said they would want to live beyond 120.

My own experience teaching an undergraduate class on the philosophy of death confirms some of these findings. At the beginning of each semester, I ask my class how long they would want to live, ideally. Contrary to what we might expect, the vast majority are content with a natural life span. They do not worry much about death. Half of the class say that they have never really thought about death. (Of course, this might be because they are young.) As someone who finds death to be a gruesome prospect, I find this easygoing attitude toward death weird. At first, I did not take it seriously. Surely they are only pretending to accept death in order to comfort themselves and each other! But when I pressed people around me on the matter, they too insisted that they were okay with dying. Really. This was not because they, like 80 percent of Americans, believed in an afterlife. People I spoke to were often agnostics, and they did not justify their equanimity by referring to heaven. Rather, they had accepted death and said that they had “made peace” with it. They had the same sentiments with regard to aging. The limiting conditions of our lives are fine to them just the way they are. Gradually it dawned on me: Could it be that what seems obvious (to me), namely, that it is bad to age and die, is actually a countercultural thought?

Stoic philosophers from Zeno to Marcus Aurelius implored us not only to accept death, but to love it as a part of the cosmically just iron laws of nature.

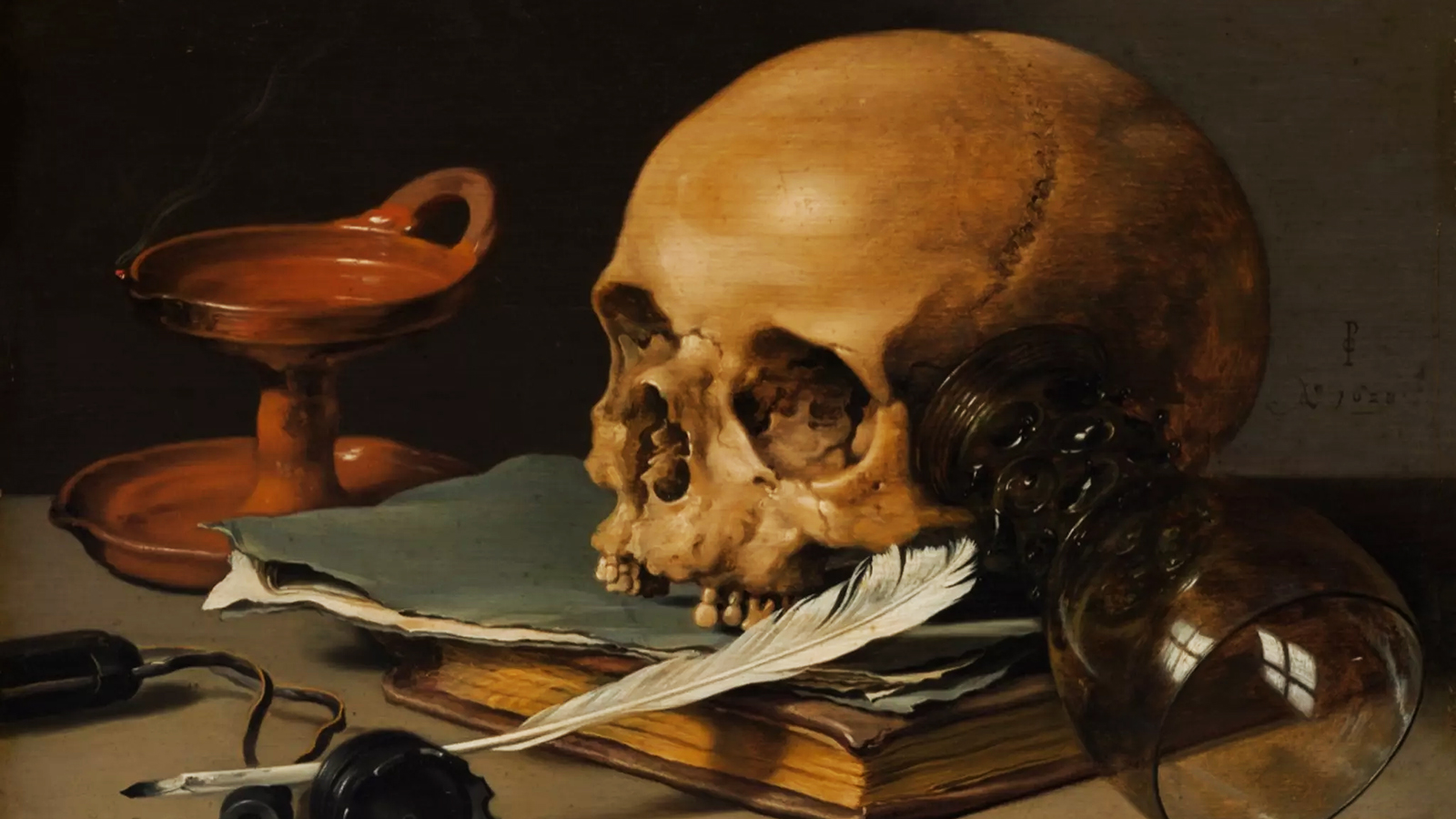

I began to study ideas about human mortality. What I found was that the acceptance of death is deeply embedded in our cultures. In the literature on death, this view is often referred to as “apologism” and contrasted with prolongevism, but it could also be labeled the “philosophical view” or the “wise view,” since all the most important philosophers and teachers of mankind have taught that we should not fear death.

Socrates likened earthly existence to a punishment and an illness and understood death to be a relief, something to look forward to. The Buddha similarly taught that life is suffering and saw our final and absolute extinction as the highest good. Stoic philosophers from Zeno to Marcus Aurelius implored us not only to accept death, but to love it as a part of the cosmically just iron laws of nature. The 16th-century thinker Montaigne, under the influence of Plato and the Stoics, goes so far as to identify philosophical wisdom with the acceptance of death in the famous title of one of his essays, “To Study Philosophy is to Learn How to Die.” Epicureans competed with Platonists and Stoics, but they agreed with these rival schools that death is nothing to fear.

In Book III of the Roman epicurean philosopher Lucretius’s “On the Nature of Things,” in a section called “On the Folly of Fearing Death,” we find nearly all of the main reasons given for not fearing annihilation that we hear to this day: (a) we have no experiences when dead, so it cannot be bad; (b) if we have had a good life, then we should “retire like a guest sated with the banquet”; (c) if we have had a bad life, then “why not make end of life and trouble?”; (d) life will get boring in the end because “all things are ever as they were”; (e) we should “yield” to the younger generation, because “one thing must be restored at the expense of others” in a natural circle of life, whereby “one thing shall never cease to rise up of another, and life is granted to none for freehold, to all on lease”; and (f) we must die to avoid overpopulation since “there must needs be substance that the generations to come may grow.”

These are a few examples of death’s ardent advocates, and the list could be continued by simply adding the name of any philosopher, or prophet for that matter, who comes to mind. The likelihood that the thinker will be against death is slim. In a recent book on our attitudes toward death, the authors conclude, with some surprise, “[C]ome to think about it, we can’t think of a single major philosopher or world religion that subscribes to the position that death is nothing more than a dreadful prospect, the worst possible cheat imaginable.” Gerald J. Gruman, author of a classic study on the history of our ideas about death, similarly concludes that “the leading intellectual currents [of the West are] extensively infiltrated by apologism: The belief that prolongevity is neither possible nor desirable.”

Many of the stories we tell bring home the apologist message. The human condition seems harsh, since it comes with aging, illness, and death. However, so the message goes, it is actually what is best for us, and if we resist it and try to change it something bad is bound to happen. This is the moral of one of the earliest known pieces of literature from the 18th century BC, the “Epic of Gilgamesh.” Gilgamesh, pained and frightened by the death of his companion, sets out to find the secret of eternal life. At one point he finds it in a plant he rescues from the depths of the ocean. When he carelessly leaves the plant on the ground to go bathing, a snake steals it. All his efforts fail in similar ways. He eventually learns that “life, which you look for, you will never find. For when the gods created man, they let death be his share, and life withheld in their own hands.”

It was also a favorite theme of the Greeks. Man’s hubris, his refusal to stay within his proper bounds, is punished: We should not fly too close to the sun. In the tale of Tithonus, Eos — the Goddess of Dawn — falls in love with Tithonus and asks Zeus to make him immortal. Zeus grants Tithonus his wish, but with a catch. While unable to die, Tithonus still ages. In the end, they could do nothing but lock the senile old man in a room where he still lies babbling incoherently. (The moral may be highly relevant today: Many fear that the quest for life extension will result in the horrific spectacle of hospital wards with row after row of senile, demented centennials.) We all know how Sisyphus was punished by the gods to push a rock up a hill for all eternity. What, though, did he do to deserve this punishment? The backstory is this: Sisyphus was a king who tricked Death into putting on handcuffs. He then locked Death in a wardrobe, and as a result, no one died any more. People were still trying to slaughter each other on the battlefield to no avail. Once order was restored and death reinstated, Sisyphus was punished by being given what he wished for — namely, immortality, but again with a catch. This is a fitting punishment thinks the apologist, since in her view life without death is in fact a never-ending, infernal pushing of the rock. Death, more peaceful than the deepest sleep, saves us from sharing Sisyphus’s fate. Thank you, Death.

We are living in a time that has much less respect for the notion of hubris, but many of our most popular works of imagination continue in the tradition of the acceptance of death.

These are, of course, old myths, and we are living in a time that has much less respect for the notion of hubris, but many of our most popular works of imagination continue in the tradition of the acceptance of death. This may not be obvious until one reflects on it. Yet in what popular work of art does a quest for immortality end well? In what work of art does the hero seek immortality but is stopped by the villain? “The Lord of the Rings,” “Narnia,” “Harry Potter,” and the “Star Wars” series, to mention some of our most beloved and widely recognized stories, all reinforce the apologist narrative. Both J. R. R. Tolkien’s and C. S. Lewis’s fantasy epics were written as responses to what both authors saw as disturbing and dehumanizing science-driven visions for humanity, advanced by writers such as Julian Huxley, J. B. S. Haldane, and Olaf Stapledon.

In “The Lord of the Rings,” earthly paradise is a low-tech pastoral old Britain, whereas evil is created in the industrial furnaces of Sauron. The story centers around a magical ring, the One Ring, which can give its bearer great powers, including life extension. But it also corrupts: After having lived five times his natural life span, one of its possessors literally turns into the slimy creep Gollum. Only the Ainur, including wizards, and the elves are immortal. Men, dwarves, hobbits, and most other races cannot live forever and thus are subject to aging and natural death. In Tolkien’s universe, despite many having a desire for it, immortality is not desirable for those who are mortal. Every race has a set span; to exceed this span proves to be agony.

Peter Jackson, who directed the films based on the books, is not alone in interpreting the One Ring as representing science and technology, as well as their seemingly uncontrollable powers. Even the best, with the best of intentions, cannot control it. We must renounce its powers and return to a more natural way of being in order to save ourselves.

In the first two installments of C. S. Lewis’s “Narnia” series, Jadis, a young princess, violates the law of Aslan and eats a magical apple from the Silver Tree, which gives her inexhaustible powers and immortality but also transforms her into the psychopathic, mass-murdering archvillain, the White Witch. In J. K. Rowling’s “Harry Potter” series, the archnemesis is the formidable black magician, Voldemort, who, according to Wikibooks, “apparently believes nothing is worse than death; perhaps his greatest weakness is his inability to love.” Taken together, Lewis, Rowling, and Tolkien have sold 600 million copies of their books, far more than any other literature except for a few religious texts, all of which are, of course, also apologist. As movie adaptations — again taken together — they have grossed more than any other franchise, constituting a quarter of the top 40 grossing films of all time.

Speaking of films, while the first three installments of the “Star Wars” saga did not seem to be concerned with either hubris or death, the prequels showed themselves, at least partly, to be another cautionary tale about what happens if we do not accept death. Darth Vader, we learn, was once a young Jedi Knight whose final turn to the dark side was an effort to save his beloved princess from dying in childbirth. The Jedi Master Yoda, a personification of wisdom, encapsulates the moral: “Death is a natural part of life. Rejoice for those around you who transform into the Force. Mourn them do not. Miss them do not. Attachment leads to jealousy. The shadow of greed, that is.”

Moving beyond art, apologism is also the faith of our leading bioethicists. Leon Kass, the former chairman of the President’s Council on Bioethics, writes in his book “Life, Liberty, and the Defense of Dignity” that death “is a blessing for every human individual, whether he knows it or not,” and he complains that “the desire to prolong youthfulness [is] an expression of a childish and narcissistic wish incompatible with devotion to posterity.”

Fellow council member Francis Fukuyama warns that a graying population poses a wide range of threats, from economic collapse to the inability to defend our country. Daniel Callahan, another leading bioethicist, argues in favor of setting limits to how medicine is used. We should enable people to live well, but we should not seek to prolong their lives. Heart transplants, for example, should be reserved for younger patients, even given relatively ample resources, whereas the priority with older patients is to enable the best quality of life during their remaining years. Callahan believes a full human life is possible to achieve by 65. After 80, one’s death is still sad but not a tragedy; it is a tolerable death. Callahan rests his idea of a tolerable death on the concept of a “natural life span,” which he bases on “a persistent pattern of judgment in our culture and others of what it means to live out a life.” This “persistent pattern of judgment” referred to by Callahan is what I am referring to as the Wise View.

Thanatophobia, the fear of death, is, according to the mental health profession, no more rational than a fear of spiders, open spaces, or clowns.

In an echo of Soviet-style psychology, psychologists have even defined acceptance as the only sane, well-adjusted response to death. Thanatophobia, the fear of death, is, according to the mental health profession, no more rational than a fear of spiders, open spaces, or clowns. It is a product of “intrapsychic structural tension,” “infantile conflict,” or some other pejoratively labeled state. Kübler-Ross’s popular grief cycle model of how to face death and other forms of serious loss, by moving through the stages of denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and finally acceptance, was initially intended to be strictly descriptive. However, it is often appropriated as a normative model of a healthy mind: We ought to move from denial to acceptance, and if we do not, then there is something wrong with us.

Should we naively insist that surely death — our own or that of a loved one — is simply gruesome, then philosophers, priests, and psychologists stand ready with their wisdom to tell us not to rage and rebel, but to relax and accept death because life has an end because it has a beginning, and it consists of different stages, each one with its particular meaning and charm, not unlike the seasons of the year. The limit of death raises the stakes; it makes each moment significant, each choice important, and it endows life with seriousness and meaning. We should seek a good life, not necessarily a long life. Death is a fitting culmination to a complete life, a well-deserved rest. A fear of death is foolish since either you cease to exist and can therefore not be harmed in any way (since you are not), or you go to a better place. Immortality should not be sought by greedily hanging on to our own particular existence, by refusing to yield and make space. Immortality should be sought in transcendence, in passing the flame of life on through our children, by contributing to the achievements of man, and through the religious and philosophical appreciation of the fundamental oneness of all being. The fact that many people seek to extend youth and postpone death at any cost is a sign of selfishness and decadence. It is hubristic, Promethean, and positivist. Death can be beautiful.

This may sound persuasive, but we should not buy it. Despite its dominance, its distinguished defenders, and its impressive provenance, the Wise View is false. If death is the end then it is simply awful, and it is time we admit it.

Unless there is an afterlife, we will all die — that much is undeniable. But it matters whether we die at 90 or 150. And it matters whether we continue to fall rapidly apart after 50, or if we can delay aging enough to continue in robust health far beyond that. Indeed, from the point of view of health, and healthcare, nothing can have a greater positive impact than addressing aging. Not to speak of the suffering it would prevent.

The Wise View, with its conservative acceptance of the status quo, stands in the way of a greater societal commitment to finding out what aging is, and slow it down, halt it, or perhaps even reverse it. Thankfully, we find ourselves at a turning point in history where the old stories in praise of human mortality are beginning to lose their grip. We are less willing to see death as a just divine punishment, less certain of an afterlife, less inclined to accept that everything that happens by nature is thereby good, and we are no longer certain that nothing can be done about death. We are beginning to allow ourselves to openly admit what our actions already say: namely, that we want youth and life and that we hate aging and death. A rebellion against death is brewing.

Ingemar Patrick Linden taught philosophy at NYU for nearly a decade. He is researching public attitudes to radical life extension. This article is adapted from his book, “The Case Against Death.”

This article was originally published on MIT Press Reader.