Lobsters don’t die from old age — they die from exhaustion

- Since the beginning of time, humans have fantasized over and quested for eternal life.

- Lobsters and a kind of jellyfish offer us clues about what immortality might look like in the natural world.

- Evolution does not lend itself easily to longevity, and philosophy might suggest that life is more precious without immortality.

One of the oldest pieces of epic literature we have is known as the Epic of Gilgamesh. It’s easy to get lost in all the ancient mythology — talking animals and heroic battles — but at its heart lies one of the most fundamental and universal quests of all time: the search for immortality. It’s all about Gilgamesh wanting to live forever.

From Mesopotamian poetry to Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, from golden apples to the philosopher’s stone, humans, everywhere, have wanted and sought after eternal life.

And yet, perhaps the secret to immortality is not as elusive as we might think. Rather than holy objects or science fiction, we need only look to the animal world to see how nature, that most magical of places, might be able to answer one of the oldest questions there is.

Eternal crustaceans

If you ever find yourself at Red Lobster or about to munch into a lobster roll, take a moment to consider that you might just be eating a clue to perpetual youth. To see why, we have to know a tiny bit about aging.

As you get older, it’s impossible not to notice how everything creaks a little more, how easy jobs now require great effort, and how hangovers are no longer a laughing matter. Our bodies are designed to degrade and wear away. This deterioration, known as “senescence” in biology, occurs at the cellular level. It’s when the cells in our body stop dividing, yet remain in our body, active and alive. We need our cells to divide so that we can grow and repair. For instance, when we cut ourselves or lift weights in the gym, it is cell division that replaces and rebuilds the damage done. But, over time, our cells just stop dividing. They stay around to do the best they can, but like the macroscopic humans they make up, cells get slower and more error-prone — and so, we age.

But not lobsters. In normal cases of cell division, the shields at the end of our chromosomes — called telomeres — are remade a bit smaller, and so a bit less effective after each subsequent cell division at protecting our DNA. When this reaches a certain point, the cell enters senescence and will stop dividing. It won’t self-destruct but will just carry on and wallow as it is. Lobsters, though, have a special enzyme (unsurprisingly, called telomerase) which makes sure that their cells’ telomeres remain as long and brilliant as they’ve always been. Their cells will never enter senescence, and so a lobster just won’t age.

However, what evolution giveth with one hand, it taketh with another. As crustaceans, their skeleton is on the outside, and having a constantly growing body means they are always outgrowing their exoskeletal homes. They need to abandon their old shells and regrow a new one all the time. This, of course, requires huge reserves of energy, and as the lobster reaches a certain size, it simply cannot consume enough calories to build the shell equivalent of a mansion. Lobsters do not die from old age but exhaustion (as well as disease and New England fisherman).

The jellyfish that reverses its life cycle

Although lobsters might not have perfected immortality, perhaps there’s something to learn.

But there’s another animal that does even better than the lobster, and it’s the only creature recognized to be properly immortal. That’s the jellyfish known as Turritopsis dohrnii. These jellyfish are tiny — about the size of a fly at their biggest — but they’ve mastered one ridiculous trick: they can reverse their life cycle.

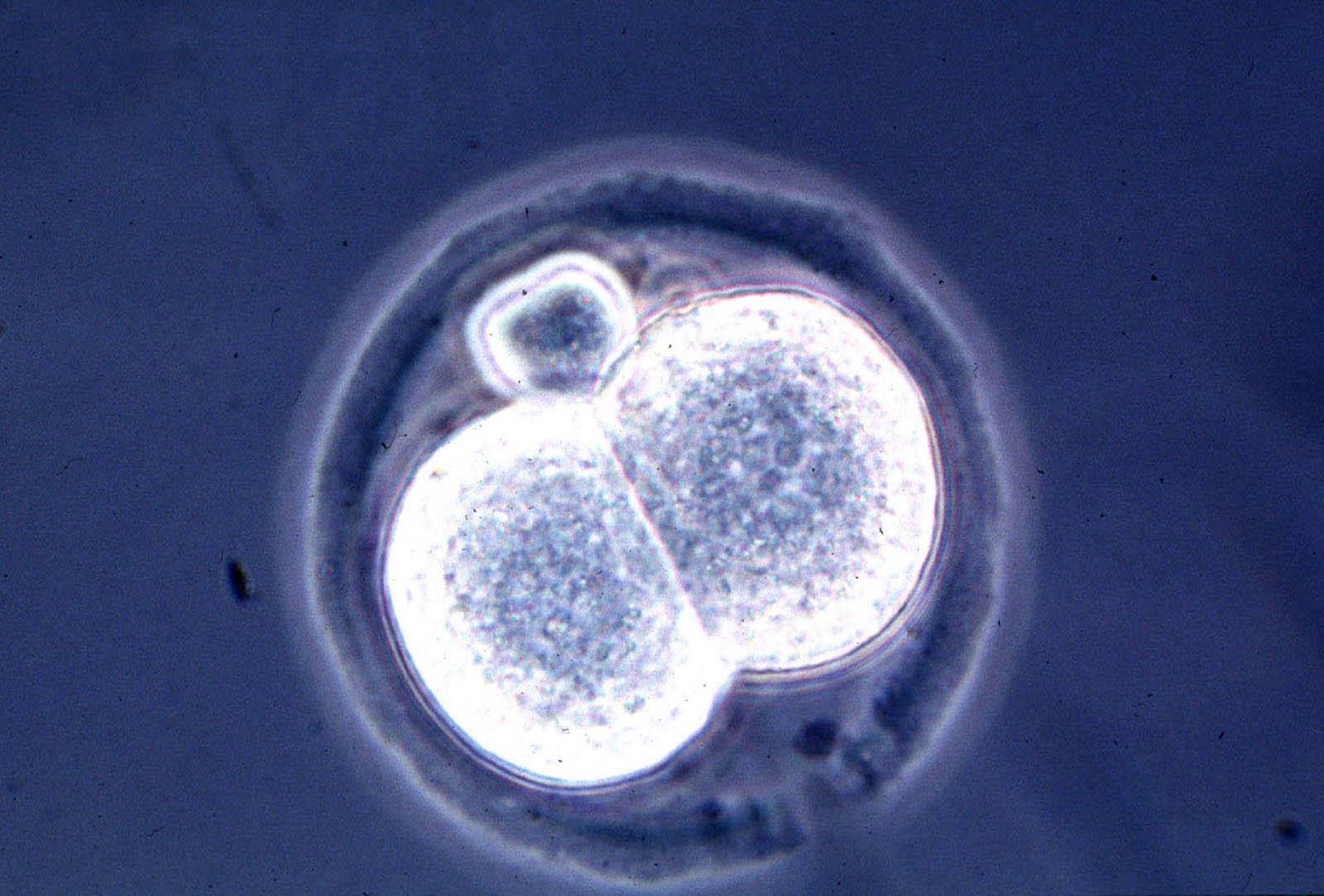

An embryonic jellyfish starts as a fertilized egg before hooking onto some kind of surface to then grow up. In this stage, they will stretch out to look like any other jellyfish. Eventually, they will break away from this surface to become a mature, fully developed jellyfish, which is in turn ready to reproduce. So far, so normal.

Yet Turritopsis dohrnii does something remarkable. When things get tough — like the environment becomes hostile or there’s a conspicuous absence of food — they can change back to one of the earlier stages in their lifecycle. It’s like a frog becoming a tadpole or a fly becoming a maggot. It’s the human equivalent of a mature adult saying, “Right, I’ve had enough of this job, that mortgage, this stress, and that anxiety, so I’m going to turn back into a toddler.”. Or, it’s like an old man deciding to become a fetus again, for one more round.

Obviously, a fingernail sized jellyfish is not immortal as we’d probably want the word to mean. They’re as squishable and digestible as any animal. But, their ability to change back to earlier forms of life, ones which are better adapted to certain environments or where there are fewer food sources, means that they could, in theory, go on forever.

Why do we want to live forever?

Although the quest for immortality is as old as humanity itself, it’s surprisingly hard to find across the diverse natural world. Truth be told, evolution doesn’t care about how long we live, so long as we live long enough to pass on our genes and to make sure our children are vaguely looked after. Anything more than that is redundant, and evolution doesn’t have much time for needless longevity.

The more philosophical question, though, is why do we want to live forever? We’re all prone to existential anguish, and we all, at least some of the time, fear death. We don’t want to leave our loved ones behind, we want to finish our projects, and we much prefer the known life to an unknown afterlife. Yet, death serves a purpose. As the German philosopher Martin Heidegger argued, death is what gives meaning to life.

Having the end makes the journey worthwhile. It’s fair to say that playing a game is only fun because it doesn’t go on forever, a play will always need its curtain call, and a word only makes sense at its last letter. As philosophy and religion has repeated throughout the ages: memento mori, or “remember you’ll die.”

Being mortal in this world makes life so much sweeter, which is surely why lobsters and tiny jellyfish have such ennui.

Jonny Thomson teaches philosophy in Oxford. He runs a popular Instagram account called Mini Philosophy (@philosophyminis). His first book is Mini Philosophy: A Small Book of Big Ideas