Anatoly Yevgenyevich Karpov was the world chess champion for a decade, from 1975 to 1985. He won the title when Bobby Fischer, the American grandmaster and reigning world champion, failed[…]

Sign up for Big Think on Substack

The most surprising and impactful new stories delivered to your inbox every week, for free.

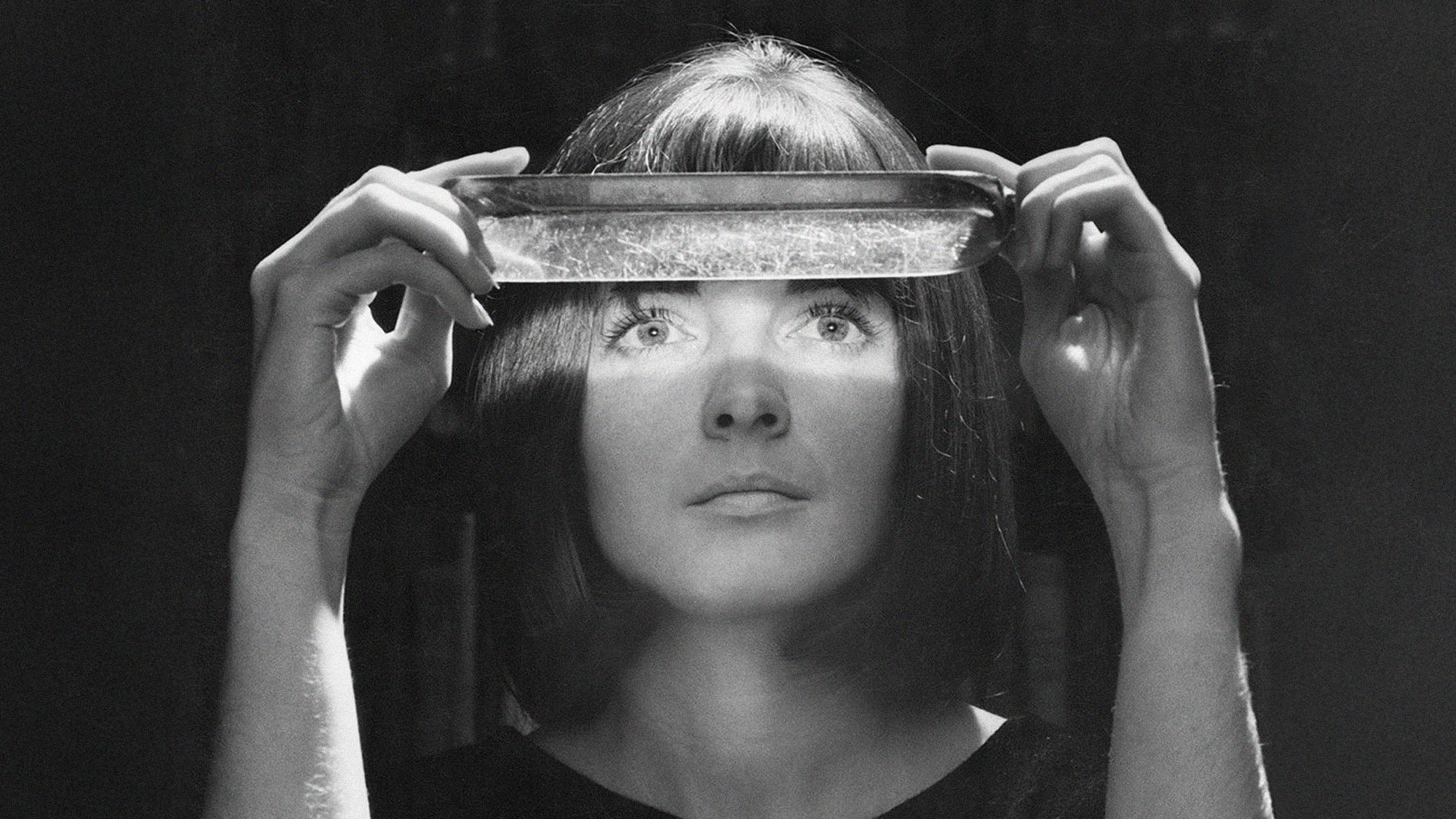

The American grandmaster was an impulsive individualist who had an incapacitating fear of losing, says the man who became world chess champion when Fischer refused to show up at the board and defend his title.

Question: How did you feel when Fischer defaulted on his worldrn title?

rn

Anatoly Karpov: So I wasn’t very happy that Fischer rndidn’t appear for the match and I made many efforts to play another rnmatch. Okay, even it could be not official match for world title, but Irn wanted to play Fischer and I met him for several times, but I believe rnhe had psychological problems at that moment. And so first of all he rncouldn’t accept to lose even one game. And so you could feel it when wern had discussions. He thought that when he became world champion he had rnno right to make one mistake or especially to lose chess game. And with rnsuch approach it is very difficult to play chess because when you meet arn player who is on the same level and very strong, you can’t avoid losingrn game. Even one game. You can win a match, but not playing without rnlosing the game. It’s almost impossible.

rnQuestion: Did you ever meet Fischer?

rn

rnAnatoly Karpov: Yes I met Fischer a couple of times and the firstrn time, I mean in this set because we met first in San Antonio in 1972 rnjust after he became world champion, after he beat Spasky in Reykjavik. rn I played in San Antonio in 1972 and then Fischer was invited by rnorganizers. He was guest of honor now for the closing ceremony and the rnfinal round. That time I met him for the first time and then we had setrn of meetings in 1976 and 1977. And so 1977, it was last time and we metrn here in the United States. It was in Washington D.C.

rnQuestion: What did you think of Fischer as a person?

rn

Anatoly Karpov: I must say that we had full respect of rneach other and so it was nice to talk to him. And what I could realize,rn he had no patience to listen to his partner or opponent, and if he rncould find out any ideas, he should express this immediately even he rncould interrupt the other person. He couldn’t wait. He was very rnimpulsive in this way. But I have good memory of these meetings and I rnmust say I had not any problems to contact him and to talk to him.

rnQuestion: Do you think Fischer was crazy?

rn

Anatoly Karpov: Well Fischer was always thinking that he rnbelongs to planet and he’s not a member, or citizen of one country or rnanother and he thought, okay, of course he was great star and also greatrn player, one of the greats in the history of chess, so he considered rnthat he belongs to the planet. And then he was very independent and so rnhe expressed these feelings, sometimes with very sharp sentences which Irn would not support, but this was his character.

rnQuestion: Wasn’t Paul Morphy, the only other American to become rnworld champion, also crazy?

rn

[0 0:29:01.00] Paul Morphy had another story and so he got mad rnbecause he wasn’t well accepted. If we recall the history of Paul rnMorphy, he made fantastic tour through Europe and he beat the strongest rnplayers of that time, the strongest part of the world in chess. He beat rnEuropeans and he became unofficial world champion. But then he came rnback to the United States and it was time of the problems between North rnand South, and it was Civil War and then Morphy was well accepted, rnaccepted with triumph in lots of United States but then he came back to rnhis area, and he was from South, so people there didn’t appreciate his rnvictories. And so it created a lot of personal problems and he ended rnhis life I think in the hospital.

rnQuestion: Do you have to be crazy to play great chess?

rn

Anatoly Karpov: No. Absolutely not.

Recorded on May 17, 2010

Interviewed by Paul Hoffman

rn

Anatoly Karpov: So I wasn’t very happy that Fischer rndidn’t appear for the match and I made many efforts to play another rnmatch. Okay, even it could be not official match for world title, but Irn wanted to play Fischer and I met him for several times, but I believe rnhe had psychological problems at that moment. And so first of all he rncouldn’t accept to lose even one game. And so you could feel it when wern had discussions. He thought that when he became world champion he had rnno right to make one mistake or especially to lose chess game. And with rnsuch approach it is very difficult to play chess because when you meet arn player who is on the same level and very strong, you can’t avoid losingrn game. Even one game. You can win a match, but not playing without rnlosing the game. It’s almost impossible.

rnQuestion: Did you ever meet Fischer?

rn

rnAnatoly Karpov: Yes I met Fischer a couple of times and the firstrn time, I mean in this set because we met first in San Antonio in 1972 rnjust after he became world champion, after he beat Spasky in Reykjavik. rn I played in San Antonio in 1972 and then Fischer was invited by rnorganizers. He was guest of honor now for the closing ceremony and the rnfinal round. That time I met him for the first time and then we had setrn of meetings in 1976 and 1977. And so 1977, it was last time and we metrn here in the United States. It was in Washington D.C.

rnQuestion: What did you think of Fischer as a person?

rn

Anatoly Karpov: I must say that we had full respect of rneach other and so it was nice to talk to him. And what I could realize,rn he had no patience to listen to his partner or opponent, and if he rncould find out any ideas, he should express this immediately even he rncould interrupt the other person. He couldn’t wait. He was very rnimpulsive in this way. But I have good memory of these meetings and I rnmust say I had not any problems to contact him and to talk to him.

rnQuestion: Do you think Fischer was crazy?

rn

Anatoly Karpov: Well Fischer was always thinking that he rnbelongs to planet and he’s not a member, or citizen of one country or rnanother and he thought, okay, of course he was great star and also greatrn player, one of the greats in the history of chess, so he considered rnthat he belongs to the planet. And then he was very independent and so rnhe expressed these feelings, sometimes with very sharp sentences which Irn would not support, but this was his character.

rnQuestion: Wasn’t Paul Morphy, the only other American to become rnworld champion, also crazy?

rn

[0 0:29:01.00] Paul Morphy had another story and so he got mad rnbecause he wasn’t well accepted. If we recall the history of Paul rnMorphy, he made fantastic tour through Europe and he beat the strongest rnplayers of that time, the strongest part of the world in chess. He beat rnEuropeans and he became unofficial world champion. But then he came rnback to the United States and it was time of the problems between North rnand South, and it was Civil War and then Morphy was well accepted, rnaccepted with triumph in lots of United States but then he came back to rnhis area, and he was from South, so people there didn’t appreciate his rnvictories. And so it created a lot of personal problems and he ended rnhis life I think in the hospital.

rnQuestion: Do you have to be crazy to play great chess?

rn

Anatoly Karpov: No. Absolutely not.

Recorded on May 17, 2010

Interviewed by Paul Hoffman

▸

1 min

—

with