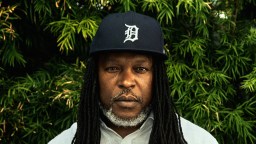

The 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution abolished slavery—but it still remains legal under one condition. The amendment reads: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” Today in America, big corporations profit of cheap prison labor in both privatized and state-run prisons. Shaka Senghor knows this second wave of slavery well—he spent 19 years in jail, working for a starting wage of 17 cents per hour, in a prison where a 15-minute phone call costs between $3-$15. In this video, he shares the exploitation that goes on in American prisons, and how the 13th Amendment allows slavery to continue. He also questions the profit incentive to incarcerate in this country: why does America represent less than 5% of the world’s population, but almost 25% of the world’s prisoners? Shaka Senghor’s latest venture is Mind Blown Media.

Shaka Senghor: So prisons in America specifically are some of the biggest, most dysfunctional businesses we have in our society, and they are a business because of the cheap and free labor.

When you read the 13th Amendment—that basically was the amendment that broke through slavery and freed the men and women who were enslaved at the time—there is a clause in there that allows for the re-enslavement of people in the event that they’re convicted of a crime. And so in prisons throughout our country, you have people who are working for basically free, and if they’re not working for free they’re working for wages that, if we saw that happening in another country, we would be very critical of.

When I was in prison I worked for $0.17 an hour; that was my starting rate working in the kitchen. But there are also big corporations who invest in prison labor because they can get this labor for $1.50 an hour. The sad part about it is that, in turn, they don’t even hire these men and women when they’re actually released from prison. Everything in prison has inflated costs. It costs us—inside prison, when I was inside—anywhere between $3 and $15 for a 15-minute phone call.

We don’t have to pay that out here in free society. There is a way that we can send emails to men and women inside prison, and it cost five cents every time we send that, whereas out here in society we can send emails without any charge. And so there are so many ways that the prison is exploited: the cheap labor, the cost of services and goods, and it’s a model that, sadly and unfortunately, has affected a large segment of our society.

I think most people aren’t aware of why the business models of prison exist, because most of our society has been left clueless in regards to how our judicial system works. And it’s largely been through the effect of campaigns that politicians have run for years, this whole idea that one of the greatest fears you should have is crime in America. When you’re operating out of a space of fear you’re not thinking clearly, so you’re not willing to examine things that are right in front of us.

And so the way that the prison system has developed and evolved over the years, is it originally started as government-run, state-run institutions, and then people started seeing investment opportunities when the states and couldn’t keep up with the budgetary cost of incarcerating so many people. We currently have over two million men and women incarcerated throughout the country, and we represent five percent of the world population, yet we incarcerate 25 percent of the world’s incarcerated people.

And so, at some point, states could no longer keep up with those budgets, private investors moved in and seized an opportunity, and then they started structuring laws in a way that ensured that people continue to be incarcerated for the most frivolous things. Like, 40 years ago we didn’t have as many laws on the books that we have now, and when you look at how the war on drugs itself impacted incarceration rates, if you follow that pathway you’ll see how people seized on that opportunity and began to invest in private businesses.