What Does Liberty Mean to You?

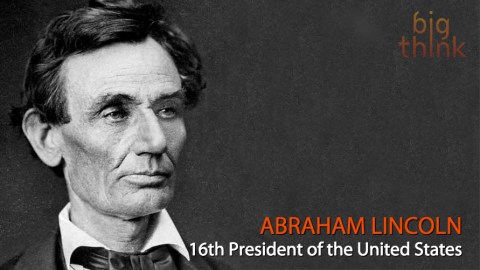

Below you’ll find some words of wisdom from Abraham Lincoln, 16th U.S. president and familiar $5 facade man. The words are derived from a speech Lincoln gave in Baltimore in April 1864, less than a year before the end of the bloody Civil War (and, consequently, about a year prior to the president’s grim assassination). The idea: We Americans like to make a huge hullabaloo about big concept words like “freedom” and “liberty” despite the fact we’ve never really bestowed upon those monikers any semblance of a thorough definition. What is liberty? Back in Lincoln’s time, two sets of Americans claimed to fight for it. Liberty meant slavery should be extinguished; liberty meant the right to own slaves.

While contexts may change, major existential dilemmas have a biting tendency to stick around much longer than anyone would like. Does anyone really believe we have a useful definition of “liberty” to hang our hats on in 2015? If Congress were in session, we’d have Democrats and Republicans arguing about this concept right now, posturing until their voices run dry. The issues they’d be arguing are hardly analogous to slavery — it’s one thing to argue about liberty in a debate about human bondage; a whole other when talking about charter schools or food stamps — but the core debate still remains rooted in our fundamental disagreement over the word.

Here’s Lincoln’s take:

“The world has never had a good definition of the word liberty, and the American people, just now, are much in want of one. We all declare for liberty; but in using the same word we do not all mean the same thing.”

Sound familiar?

We hardly have answers here at Big Think regarding what we’re going to eat for breakfast, let alone how to define the foggiest, yet most fundamental value of American democracy. Still, it’s interesting when attempting to pinpoint the source for Washington’s tedious brand of do-nothingness to lay eyes on the word “liberty” and not be able to formulate a coherent meaning — or at least a coherent meaning the person next to you would also agree with. If we understood what the word really meant to us as a whole, perhaps governing would be much easier.

Of course, if we all agreed, then there wouldn’t be much use for democracy.