Another important reason to stay fit: your independence

Photo by Wang Biao/VCG via Getty Images

- Everyone suffers from sarcopenia: the loss of muscle mass and strength due to age.

- While there are numerous benefits to exercise, an important one is remaining independent well into old age.

- Weightlifting is essential for keeping muscle mass and strength as the decades go by.

The myriad benefits of exercise are well-documented. From physical strength and emotional control, to warding off cognitive disease, weight management, and overall life satisfaction, staying fit is demanded by our biology. There’s another benefit of exercise that older populations need to consider: remaining independent well into old age.

That’s the consensus of Amanda Loudin’s recent Washington Post article. She begins by discussing an 82-year-old female powerlifter pummeling a home intruder with a table and bottle of baby shampoo. Thankfully, her incredible story was captured on video. Willie Murphy beat him so bad he begged her to call an ambulance. Fortunately (for him) the police arrived just in time to help him out.

Not everyone is Willie Murphy. But how many octogenarians would be able to fend for themselves when a younger and larger man breaks into their home? At that age, a mere slip can easily cause a hip fracture, which could quickly result in death. The fall causes the victim’s immune system to be compromised, making them more susceptible to common illnesses like pneumonia. That process is exactly what killed my grandmother.

Only in the post-Industrial world did we even need to think of exercise as separate from everyday life. For most of time, every member of a tribe had to carry their own weight. Survival required physical activity; everyone had to chip in. Sure, there was hunting—the average nomadic tribe member walked an average of 19 miles per day—but there was also squatting and bending to pick vegetables, roots, and plants, carrying water from the river, and that essential component of social coherence: play.

Movement is a biological inheritance. We do harm when not honoring that fact.

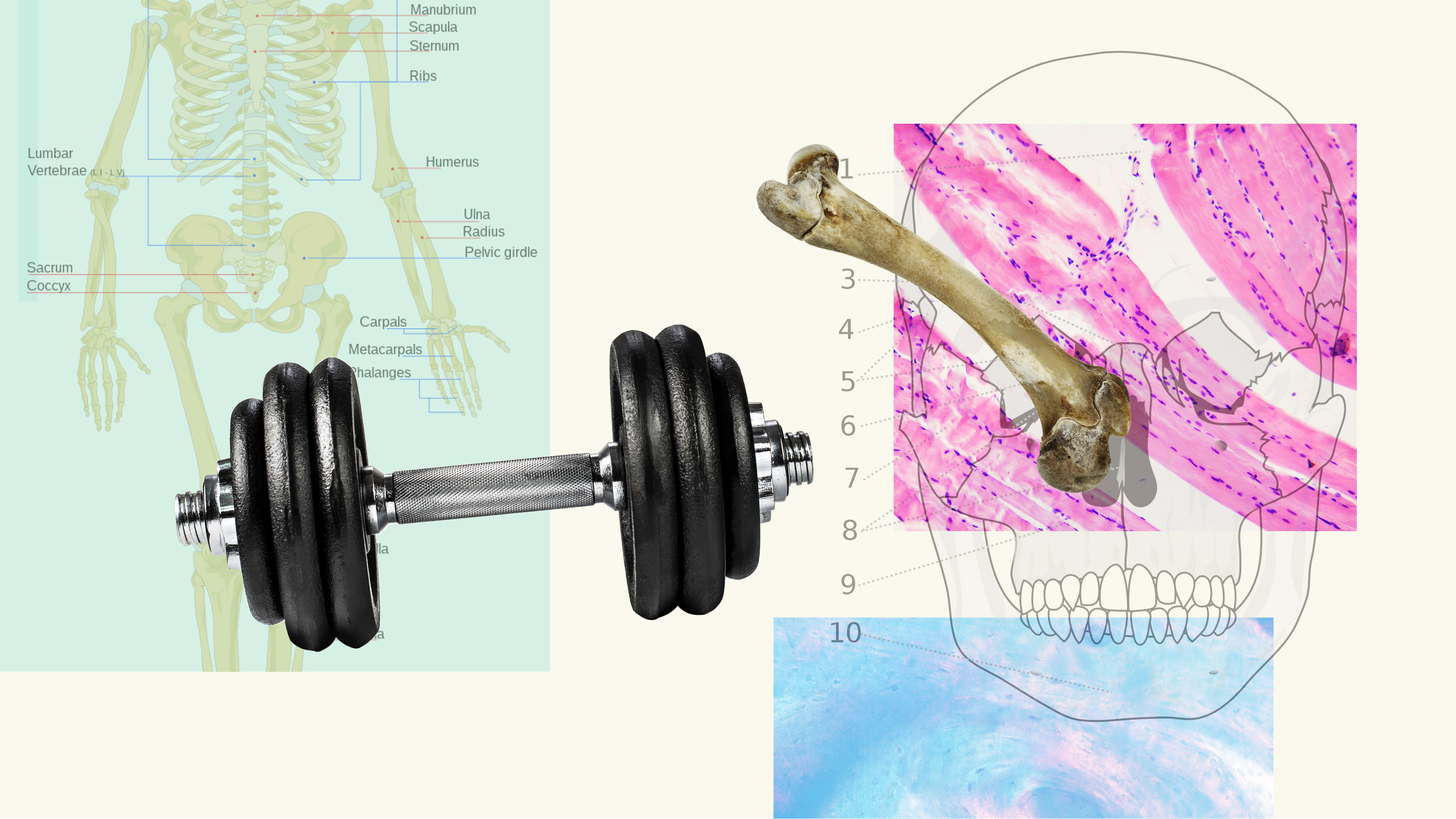

Regardless of fitness level, sarcopenia plagues everyone. The loss of muscle tissue begins in our thirties. While any exercise aids in overall health, only by lifting heavy objects (or lighter objects repetitively—”time under tension” matters) do we fend off the ravages of muscular atrophy. As sports medicine physician Matt Sedgley tells Loudin,

“When we talk about bone health and falls, we talk about three factors: fall, fragility and force. Participating in weight-bearing and resistance-training exercises helps develop muscle mass. This may help treat fragility conditions like osteoporosis. So if you fall you have stronger bone density. It may also lead to more cushioning when you do fall.”

Falling is one danger. There are other less serious (though equally frustrating) realities we face as we age. Walking up and down stairs without losing our breath. The ability to carry our groceries from the car. Speaking of cars, there’s also driving. The more we lose motor control and strength, the less we’ll be able to remain independent.

It doesn’t have to be that way. Consider Tao Porchon-Lynch, a 101-year-old yoga instructor who continues to teach workshops and dance in ballroom competitions. Her secret? She never stopped being active. When I interviewed her in 2010, shortly after taking her master class, she had just broken her wrist. Within two months, at age 91, she was doing arm balances with ease. That injury would sideline people half her age far longer. As she told me that afternoon,

“I’ve had a hip replacement. I was getting dog food at A&P. I got twisted and ended up with a pin in my hip. Health-wise, I’m seldom sick. Mentally, I don’t allow myself to think about tomorrow and what will happen. I don’t like people to tell me what I can’t do. I never thought about age.”

At that time, Porchon-Lynch lived alone, shopped for herself, and drove herself around her upstate New York community to teach five yoga classes a week. When I’ve discussed her fierce independence and incredible fitness to people over the years, some claim genes and others luck. Sure, those factor in, but that sounds more like an excuse. It reduces a lifetime of hard work to a quip that makes someone feel better about their lack of desire for putting in the work to stay healthy.

The author practicing with Tao Porchon-Lynch, Strala Yoga, New York City, 2010.

To paraphrase biomechanist and popular blogger, Katy Bowman, you are never out of shape; you are exactly in the shape you train for. If you don’t train in any capacity, your shape is going to reduce the possibility that you’ll remain independent later in life.

There are numerous arguments about exactly how to remain fit. What runs underneath all of them is that you have to move in some capacity. A 2012 review of sarcopenia in older adults details its causes and consequences, as well as offering ways of fending off inevitable decline. Aging is the obvious culprit, though the authors better define the issues:

“Its cause is widely regarded as multifactorial, with neurological decline, hormonal changes, inflammatory pathway activation, declines in activity, chronic illness, fatty infiltration, and poor nutrition, all shown to be contributing factors.”

By the eighth decade of life as much as 50 percent of muscle mass has been lost. Obesity, an increasing problem in our time, negatively contributes to this process: increased fat mass accelerates the loss of muscle tone and lean body mass. While mass tends to be the focus when defining sarcopenia, strength is another factor. We get weaker as we age. But we can slow the decline through exercise and better nutrition.

Loading your body with heavy weights (or lower weights at higher repetitions) fits into the movement recipe, along with the basics: squatting, jumping, pushing, and pulling. Being able to pick up and put down weight, to pull weight to you and push it away from you, and to move through your entire range of motion on a regular basis are all basic movement patterns that help to fend off the demise of muscle mass and strength.

It is inevitable that you will become weaker and slower. Losing your independence does not have to be the end result. You can live well until the day they die. You can remain quite independent. But you have to put in the work to earn that result.

—

Stay in touch with Derek on Twitter and Facebook. His next book is Hero’s Dose: The Case For Psychedelics in Ritual and Therapy.