Tim Brinkhof

Tim Brinkhof is a Dutch-born, New York-based journalist reporting on art, history, and literature. He studied early Netherlandish painting and Slavic literature at New York University, worked as an editorial assistant for Film Comment magazine, and has written for Esquire, Film & History, History Today, and History News Network.

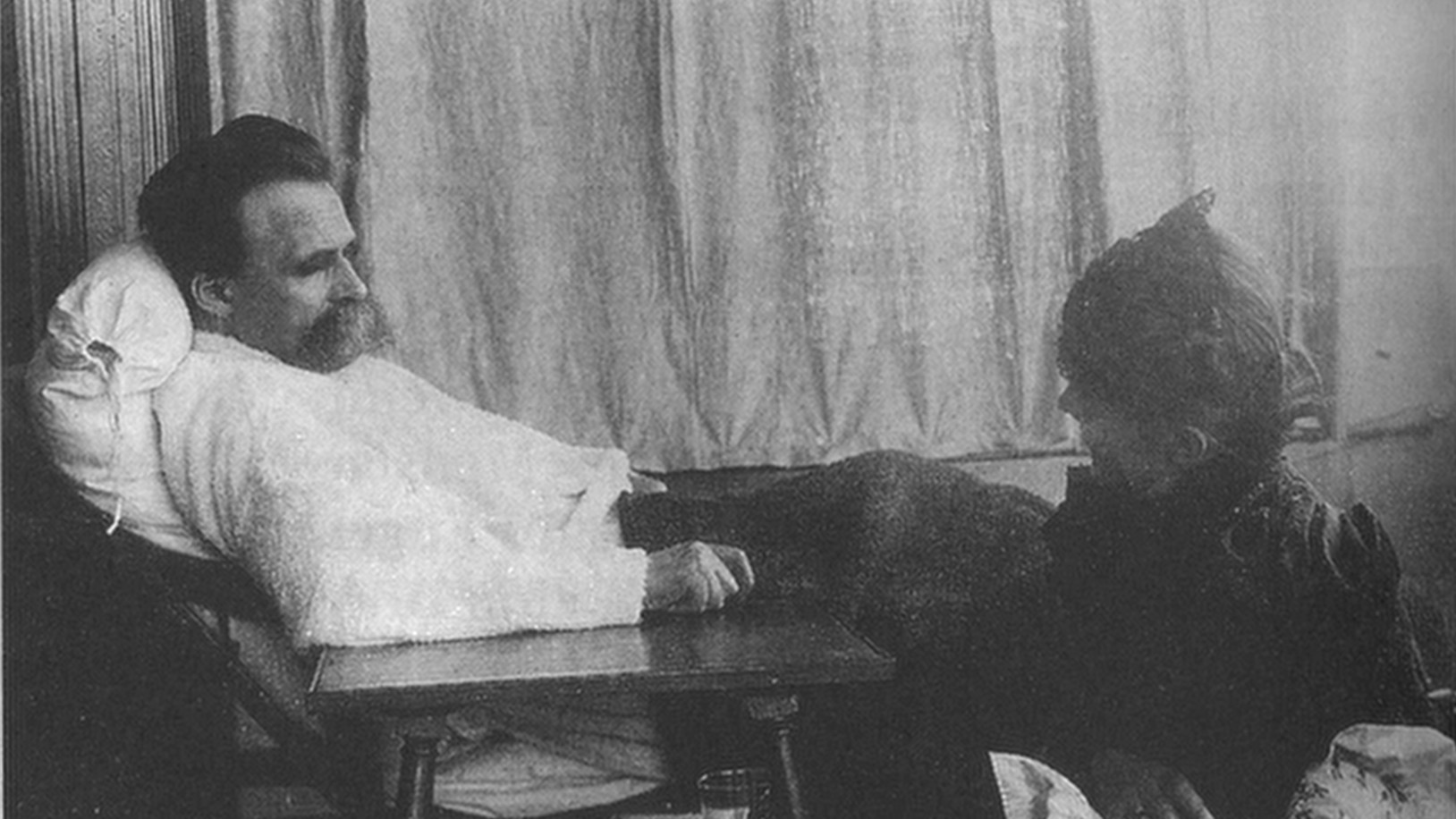

The great philosopher spent the final portion of his painful life in a vegetative state. Did illness get him there, or was it his own philosophy?

Once at the pinnacle of Amsterdam’s art scene, Rembrandt van Rijn eventually found himself outcompeted by his own students.

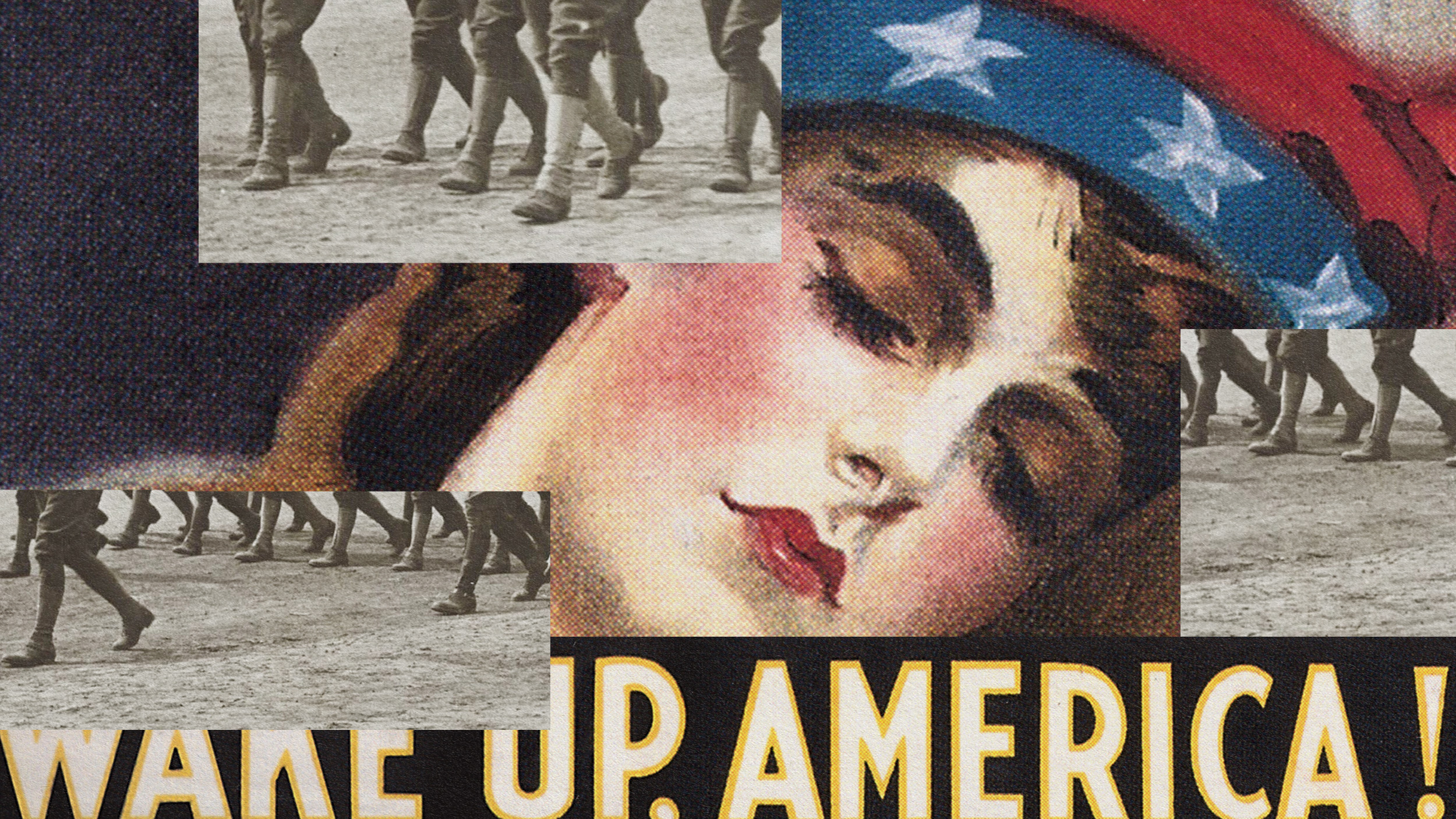

Rejecting romanticism, these famous paintings depict war as it really is: sadistic and senseless.

China has always been one of the world’s wealthiest nations, but Chinese wealth looks different across the country’s eventful history.

In war zones, aggressors steal art to eradicate the cultural heritage of others. Victims, meanwhile, sell stolen art in order to survive.

The Persian Constitutional Revolution made unlikely allies and enemies of missionaries, ayatollahs, the shah, and his Russian ambassadors. Its legacy shaped modern-day Iran.

In ancient Rome, collective bathing was the norm. In the West today, it’s the exception — and that’s too bad.

The world’s “most produced living playwright” wins out over other contestants, including Salman Rushdie and Margaret Atwood.

Science and technology were making early modern Europe a better place to live, but at what cost?

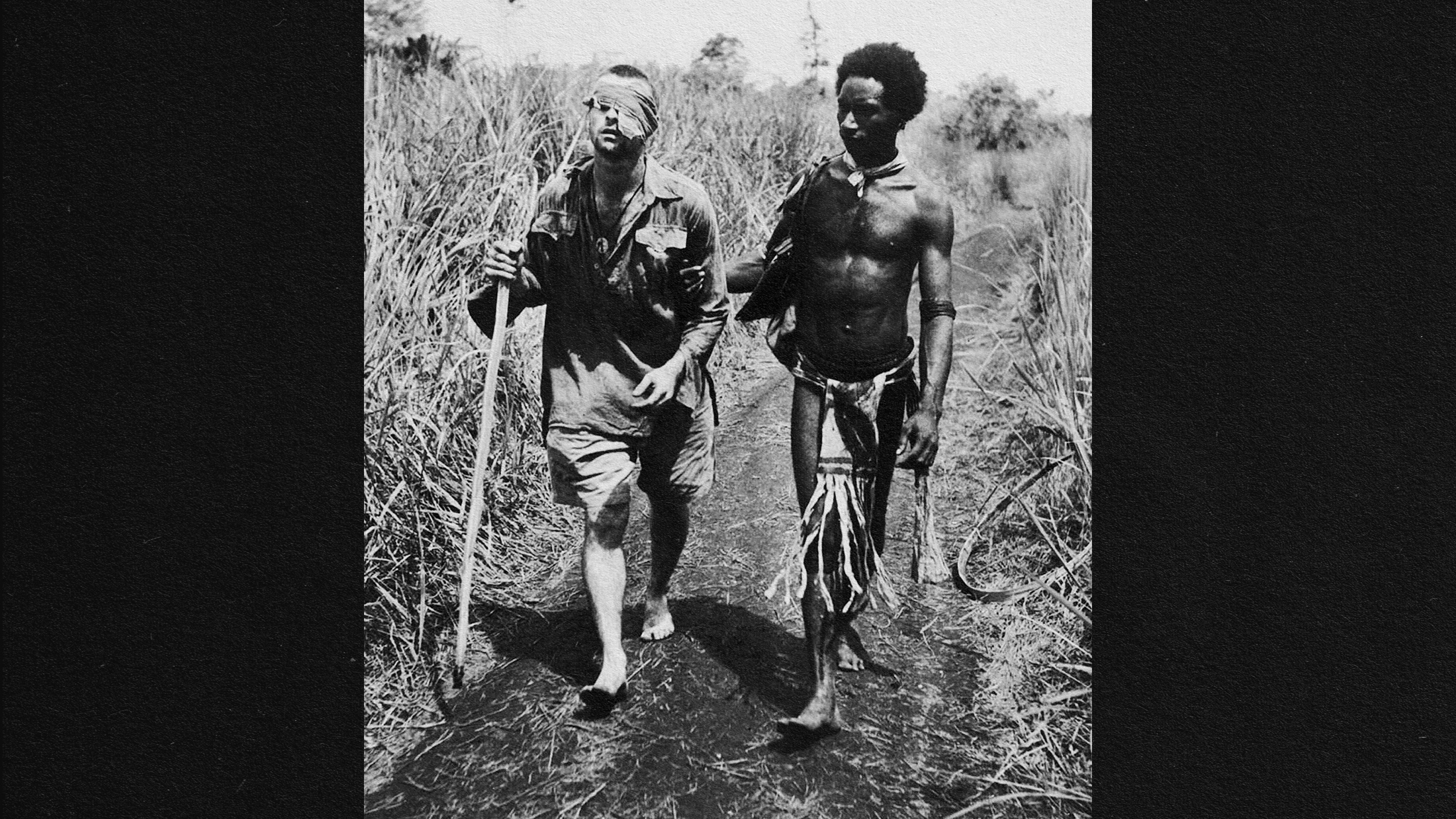

Australian soldiers fighting the Japanese recruited native New Guineans to their campaign.

Historians have been able to piece together a clear picture of how the average Roman citizen spent their waking hours.

His crime was so great, he was not only sentenced to death but his name was to be erased from memory.

Still, the author’s main argument wasn’t totally discredited.

The design was as intricate as that of modern-day, factory-fabricated denim jeans, and just as durable. The ancients had fashion.

Pure cinema is about removing redundancy so that even the smallest detail serves a purpose in relation to the bigger picture.

The region of Catalonia has been at odds with greater Spain for over 300 years. The prospect of autonomy remains a distant and fading dream.

The polymath used science to elevate his art.

Nero’s reputation as one of the most malevolent emperors in Roman history might be partly slander.

Explore how belief shapes destiny, from Oedipus Rex to modern geopolitics.

The arsons were no accident, archaeological evidence suggests.

Only Caesar lived to tell the tale.

Voyage into the lawless world of experimental literature.

The Te’omim Cave in the Jerusalem Hills is filled with skulls and oil lamps — objects a new study says may have been used in dark rituals.

What better explains the prevalence of heavy metal in Scandinavian countries: culture or economy?

These initially sympathetic characters take readers down a dark path.

Those white, marble statues you see in museums all over the world were originally painted with bright colors.

Mounted on horses and armed with unique, powerful bows, the archers of Genghis Khan inspired terror wherever they rode.

A classical equivalent to Chanel No. 5.

Hybrid animals emerge when two different species from the same family reproduce. For many years, the kunga’s lineage was just another genetic mystery.

Aiming to unlock the secrets of his unconscious mind, Jung experimented with intensive daydreaming.