10 Women of Philosophy, and Why You Should Know Them

While a great idea can come from anybody anywhere, sometimes a different perspective is needed for progress to be made. In that mindset, today we have ten of the greatest female philosophers of all time.

1. Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986)

As a French existentialist, Marxist, and founding mother of second-wave feminism, there are few philosophers who can hold a candle to Beauvoir, though she never thought of herself as being one. She wrote dozens of books, including The Second Sex and The Ethics of Ambiguity, and is noted for having a very accessible writing style. Her work is often focused on the pragmatic matters of existentialism, as opposed to that of her life partner, Jean-Paul Sartre. She was very active in French politics, as a social critic, protester, and member of the French resistance.

“The curse which lies upon marriage is that too often the individuals are joined in their weakness rather than in their strength, each asking from the other instead of finding pleasure in giving.”

2. Hypatia of Alexandria (Born c. 350–370, died 415 AD)

A Greek philosopher and scientist, she was regarded by many of her contemporaries as the greatest philosopher of the age. Her fame was such that prospective students traveled great distances to hear her speak. While it remains uncertain as to the scope of her writings, a common problem for ancient authors, it is agreed that she at least co-wrote several surviving works with her father, including extensive commentaries on Greek science and philosophy. She was killed by a Christian mob as part of larger riots in the city, though there is some evidence to suggest that she was assassinated over controversial astronomical work.

“There was a woman at Alexandria named Hypatia, daughter of the philosopher Theon, who made such attainments in literature and science, as to far surpass all the philosophers of her own time.” – from Socrates of Constantinople

3. Hannah Arendt (1906-1975)

Another great philosopher who didn’t consider herself one. The German born Arendt, who escaped Vichy France for New York, wrote extensively on totalitarianism during her life. Her magnum opus, The Origins of Totalitarianism, analyzes and explains how such governments come to power. Likewise, her book Eichmann in Jerusalem,considers how the most average of men can be made evil in the right conditions. She also wrote on other political subjects, such as the American and French revolutions, and offered a critique of the idea of human rights.

“Under conditions of tyranny it is far easier to act than to think.”

4. Philippa Foot (1920-2010)

An English philosopher working out of Oxford and UCLA, she is often credited with sparking a revival in Aristotelian thought. Her work in ethics is extensive and well known: she wrote the trolley problem. Over her lifetime she worked with many philosophers (including our next entry), and heavily influenced many living philosophers. A collection of her essays, Virtues and Vices, is a key document for the recently revitalized interest in virtue ethics.

“You ask a philosopher a question and after he or she has talked for a bit, you don’t understand your question anymore.”

5. G.E.M Anscombe (1919-2001)

A British philosopher working out of Oxford who wrote about everything she could lay her hands on, including logic, ethics, meta-ethics, the mind, language, and war crimes. Her greatest work was Intention, a series of papers showing how what we intend to happen has a great effect on our ethical standing. Her groundbreaking work Modern Moral Philosophy,has influenced modern ethical work extensively; it was here that she invented the word consequentialism. She also debated many famous thinkers, including Phillipa Foot. She was also a notable firebrand, protesting both Harry Truman and local abortion clinics.

“Those who try to make room for sex as mere casual enjoyment pay the penalty: they become shallow.”

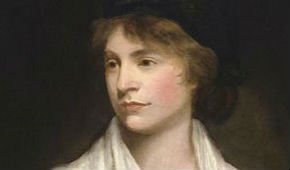

6. Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797)

An English philosopher and popular writer, she was the author of A Vindication of the Rights of Men, a defense of the French Revolution against Burke; andA Vindication of the Rights of Woman,an answer to those who argued against the education of women. She was, in some ways, the first feminist philosopher. She also wrote several novels, travel guides and a children’s book. She died from complications of childbirth at age 38. That birth gave us her daughter, who was also a noted writer: Mary Shelly, author of Frankenstein.

“Virtue can only flourish amongst equals.”

7. Anne Dufourmantelle (1964-2017)

Image: Librairie Mollat

A French philosopher and psychoanalyst, her philosophy was based on risk taking. Particularly, the notion that to truly experience life we must take risks, often considerable ones. She discussed the notion of “security” which frowns on risk while also leaving a void in our existence. She was the author of 30 books, has many interesting lectures, and died as she lived.

“When there is really a danger to be faced, there is a very strong incentive to devotion, to surpassing oneself.”

8. Harriet Taylor Mill (1807-1858)

Wife of John Stuart Mill, Harriet Mill was a philosopher in her own right. Despite publishing few works during her lifetime, her influence on her husband’s work is undeniable. Her essay The Enfranchisement of Women is a precursor to Mill’s later work The Subjection of Womenand makes many of the same points. John Stuart Mill’s masterpiece On Libertyis dedicated to her, and by his admission partly written by her.

“All my published writings were as much my wife’s work as mine; her share in them constantly increasing as years advanced.” — J.S. Mill

9. Kathryn Gines (Born 1978)

A Philosopher working out of Pennsylvania State University, Gines has written a book on Hannah Arendt’s philosophy. A continental philosopher, she has written extensively on Africana philosophy, black feminism, and phenomenology. A collection of her work can be found here.

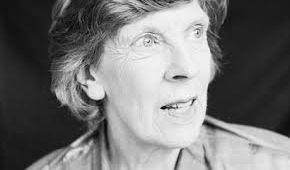

10. Carol Gilligan (Born 1936)

The founder of the school of care ethics, Gilligan’s work In a Different Voicehas been called “The little book that started a revolution.”Her work questions the value of universal standards of morality, such as fairness or duty, seeing them as impersonal and distant from our problems. She instead proposes that we consider relationships and our interdependence in moral actions.

“I’ve found that if I say what I’m really thinking and feeling, people are more likely to say what they really think and feel. The conversation becomes a real conversation.”