Einstein’s letter to Freud about the psychology of war and governance

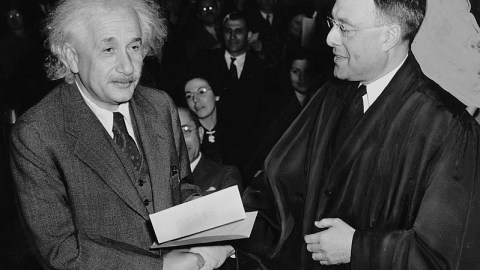

Wikimedia commons

- A little-known correspondence between Einstein and Freud reveals his thoughts on war.

- In this letter, Einstein puts forth the idea for a world government run by an intellectual elite.

- His goal in this letter was to get Freud’s insight into the psychologial matter of violence and how to solve it.

Albert Einstein is synonymous with genius. While we’re all aware of his outstanding contributions to science, much of his brilliance is incomprehensible to us because it pertains to such an advanced domain of physics. That’s why it’s always enlightening to hear Einstein’s personal thoughts on a number of other issues, less scientifically esoteric and more worldly. It’s no surprise that for a man as smart as Einstein, he had a number of concerns and opinions on how to contend with some of the greatest challenges civilization faced.

In 1931 the Institute for Intellectual Cooperation invited Einstein to engage in a cross-disciplinary exchange of ideas about world politics and peace. Always up for dialectics and diverse opinions, he went ahead and began a series of letters with Sigmund Freud. This little known correspondence between these two luminaries reveals a great deal about some of Einstein’s thoughts on war, mankind and global politics.

Einstein admired Freud’s work and believed that some of his psychological ideas could help him unravel the eternal problem of man’s affinity for violence. Within these letters, the two of them discuss human nature at length and muse on both tangible and abstract ways of reducing violence and war in the world.

There is a strange sense of foreboding in these series of letters. As the onslaught of World War II had yet to rear its head, their words hold an even greater prescience and importance. Much of what they discuss are problems that still plague the world and persist, albeit with new political actors and much greater apocalyptic means of destruction.

This letter we’re going to explore illuminates an aspect of Einstein’s thinking on the notion and nature of war and world governance.

Why war? Albert Einstein’s letter to Sigmund Freud

Einstein begins his letter to Freud lamenting a common plight of intellectuals throughout the ages. The fact that we are led by the least among us. Scoundrels, profiteers, ideologues and other moronic factors of society makeup our ruling political classes. That is as true as it was then as it is today.

Referencing men like Goethe, Jesus and Kant – Einstein mentions how great spiritual and moral leaders are universally recognized as leaders even though their ability to directly affect the course of human affairs is quite limited and tangibly ineffective.

“… But they have little influence on the course of political events. It would almost appear that the very domain of human activity most crucial to the fate of nations is inescapably in the hands of wholly irresponsible political rulers.

Political leaders or governments owe their power either to the use of force or to their election by the masses. They cannot be regarded as representative of the superior moral or intellectual elements in a nation. In our time, the intellectual elite does not exercise any direct influence on the history of the world; the very fact of its division into many factions makes it impossible for its members to cooperate in the solution of today’s problems.”

Historically, this was right around the time that the League of Nations was in effect, which proved to be a futile endeavor. Einstein believed that in order to counteract this ineptitude of the ruling class, an intellectual elite control would need to be established.

“In our time, the intellectual elite does not exercise any direct influence on the history of the world; the very fact of its division into many factions makes it impossible for its members to cooperate in the solution of today’s problems. Do you not share the feeling that a change could be brought about by a free association of men whose previous work and achievements offer a guarantee of their ability and integrity?”

Einstein seems to be thinking about the idea of a philosopher-king but in the form of an international council. It would include an international legislative and judicial body, while being able to settle all conflicts. In effect, it would be a perfect world government, led by the greatest among us. Yet even Einstein was even quick to temper this utopian political idea with a note of caution.

“Such an association would, of course, suffer from all the defects that have so often led to degeneration in learned societies; the danger that such a degeneration may develop is, unfortunately, ever present in view of the imperfections of human nature.”

Einstein’s main concern

Einstein approached Freud for his insight on the unconscious and because he knew that Freud’s “sense of reality is less clouded by wishful thinking.” In approaching Freud on this issue, Einstein lays out the concern by charting out man’s lust for power, greed, capacity for evil and the psychological roots of an individual being roused to violence, which inevitably leads to the communal death march of mass warfare.

The crux of Einstein’s inquiry with Freud could be summed up as the following:

Is there any way of delivering mankind from the menace of war?

“It is common knowledge that, with the advance of modern science, this issue has come to mean a matter of life and death for civilization as we know it; nevertheless, for all the zeal displayed, every attempt at its solution has ended in a lamentable breakdown.”

Einstein’s solution for an international governance of elites of mind and intellect has to first contend with a number of issues. One of those being nationalism, the crowd outgrowth of all those aforementioned psychological maladies of individual man.

“Thus I am led to my first axiom: the quest of international security involves the unconditional surrender by every nation, in a certain measure, of its liberty of action, its sovereignty that is to say, and it is clear beyond all doubt that no other road can lead to such security.”

The early 20th century saw a number of political and philosophical movements that tried to establish this type of world governance. Einstein recognized that fact and realized that there must be something deeper at play in opposition to this goal.

“The ill-success, despite their obvious sincerity, of all the efforts made during the last decade to reach this goal leaves us no room to doubt that strong psychological factors are at work, which paralyse these efforts. Some of these factors are not far to seek. The craving for power which characterizes the governing class in every nation is hostile to any limitation of the national sovereignty.”

Einstein points out that within many nations is a small group of people whose sole purpose is to advance their personal interests and power through warfare. This is the logical conclusion for any group that rises to power, regardless of their political disposition. Whether it be leftist or right rhetoric, the only way to enforce and advance their power is through violence and war.

“I have specially in mind that small but determined group, active in every nation, composed of individuals who, indifferent to social considerations and restraints, regard warfare, the manufacture and sale of arms, simply as an occasion to advance their personal interests and enlarge their personal authority.”

They manage to pull this off politically by using their control over mass media and other varied institutions.

“Another question follows hard upon it: how is it possible for this small clique to bend the will of the majority, who stand to lose and suffer by a state of war, to the service of their ambitions? An obvious answer to this question would seem to be that the minority, the ruling class at present, has the schools and press, usually the Church as well, under its thumb. This enables it to organize and sway the emotions of the masses, and make its tool of them.”

Although Einstein realized there is more than meets the eye to this answer. Underneath the surface lies not only the root of deeper problem, but also a potential solution to this very weighty inquiry into the nature of humanity.

“Yet even this answer does not provide a complete solution. Another question arises from it: How is it these devices succeed so well in rousing men to such wild enthusiasm, even to sacrifice their lives? Only one answer is possible. Because man has within him a lust for hatred and destruction. In normal times this passion exists in a latent state, it emerges only in unusual circumstances; but it is a comparatively easy task to call it into play and raise it to the power of a collective psychosis. Here lies, perhaps, the crux of all the complex of factors we are considering, an enigma that only the expert in the lore of human instincts can resolve.”

Poised in Einstein’s question to Freud is a desire to be able to identify and then remedy this “enigma of human instincts.”

Is it possible to control man’s mental evolution so as to make him proof against the psychosis of hate and destructiveness?

“Here I am thinking by no means only of the so-called uncultured masses. Experience proves that it is rather the so-called “Intelligentzia” that is most apt to yield to these disastrous collective suggestions, since the intellectual has no direct contact with life in the raw, but encounters it in its easiest, synthetic form upon the printed page.”

Einstein’s letter leaves us with a lot to think about. His letter can be read in its entirety here.

Freud’s response is equally compelling and seeks to answer a lot of the questions that Einstein put forth.

While on first glance, their conclusions may look dour, especially in light of the tragedies that befall the world only a decade later during World War II. Their blunt honesty and teardown of the problems we all face puts us one step closer to one day remedying the perils of war and unjust world governance.

But my insistence on what is the most typical, most cruel and extravagant form of conflict between man and man was deliberate, for here we have the best occasion of discovering ways and means to render all armed conflicts impossible.