Marcelo Gleiser

Theoretical Physicist

Marcelo Gleiser is a professor of natural philosophy, physics, and astronomy at Dartmouth College. He is a Fellow of the American Physical Society, a recipient of the Presidential Faculty Fellows Award from the White House and NSF, and was awarded the 2019 Templeton Prize. Gleiser has authored five books and is the co-founder of 13.8, where he writes about science and culture with physicist Adam Frank.

A fresh view of intelligence — spanning living systems from bacteria to human civilization — challenges the idea that it’s merely problem-solving.

A perfect map is as useless as it is impossible to create.

The preservation and celebration of life, and not greed, should be our primary decision-making value.

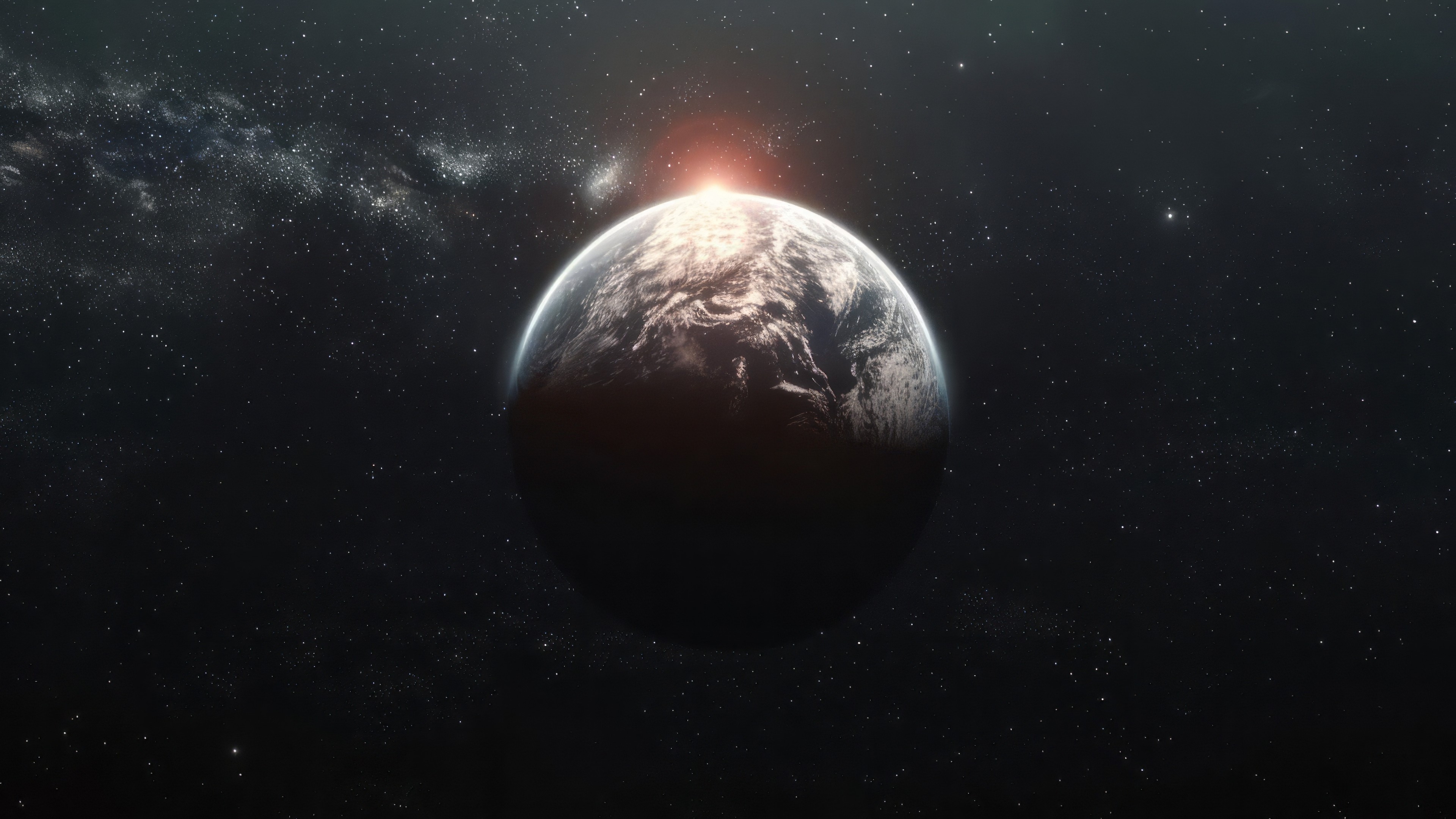

An interview with Lisa Kaltenegger, the founding director of the Carl Sagan Institute, about the modern quest to answer an age-old question: “Are we alone in the cosmos?”

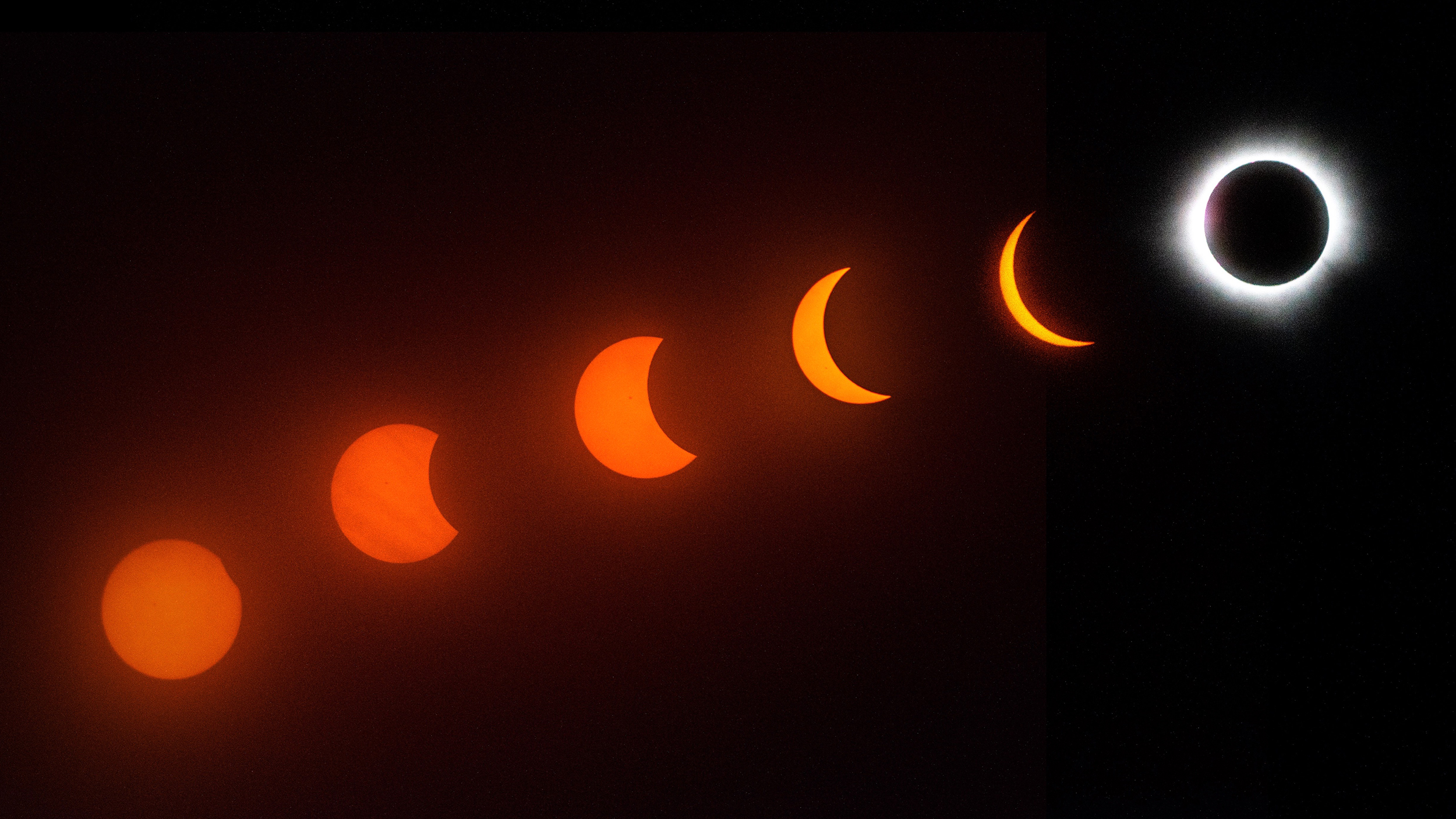

Total eclipses are a product of a strange and almost eerie cosmic coincidence — one that makes Earth an even rarer world in the galaxy and, by proxy, in the Universe.

The “first cause” problem may forever remain unsolved, as it doesn’t fit with the way we do science.

Here’s the case for why science can’t keep ignoring human experience.

13.8 columnist Marcelo Gleiser reflects on his recent voyage to Earth’s last wild continent.

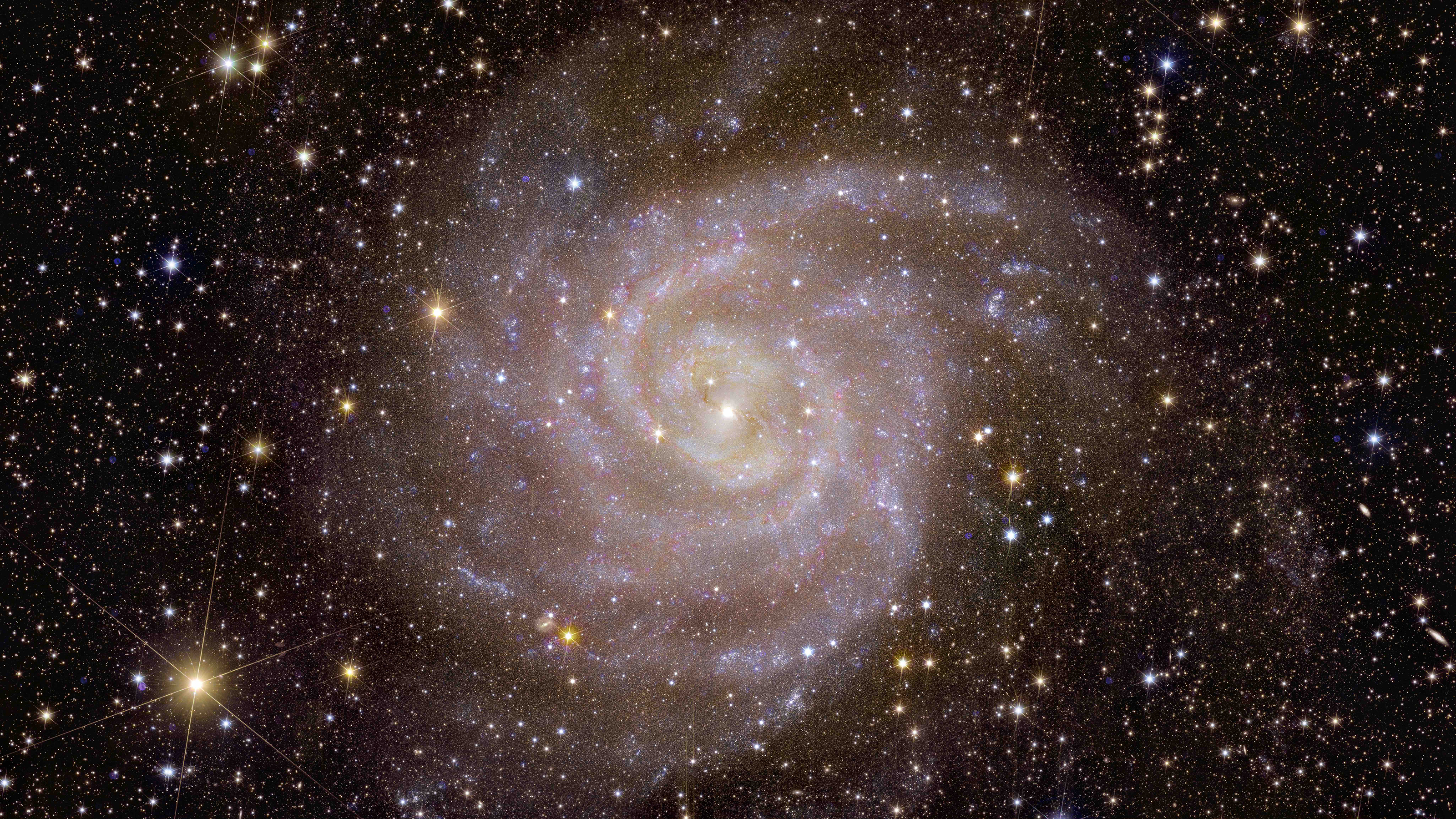

In 1924, Edwin Hubble found proof that the Milky Way isn’t the only galaxy in the Universe.

Millennia ago, philosophers like Anaximander grasped that nature is the ultimate recycler.

From how life emerged on Earth to why we dream, these unanswered questions continue to perplex scientists.

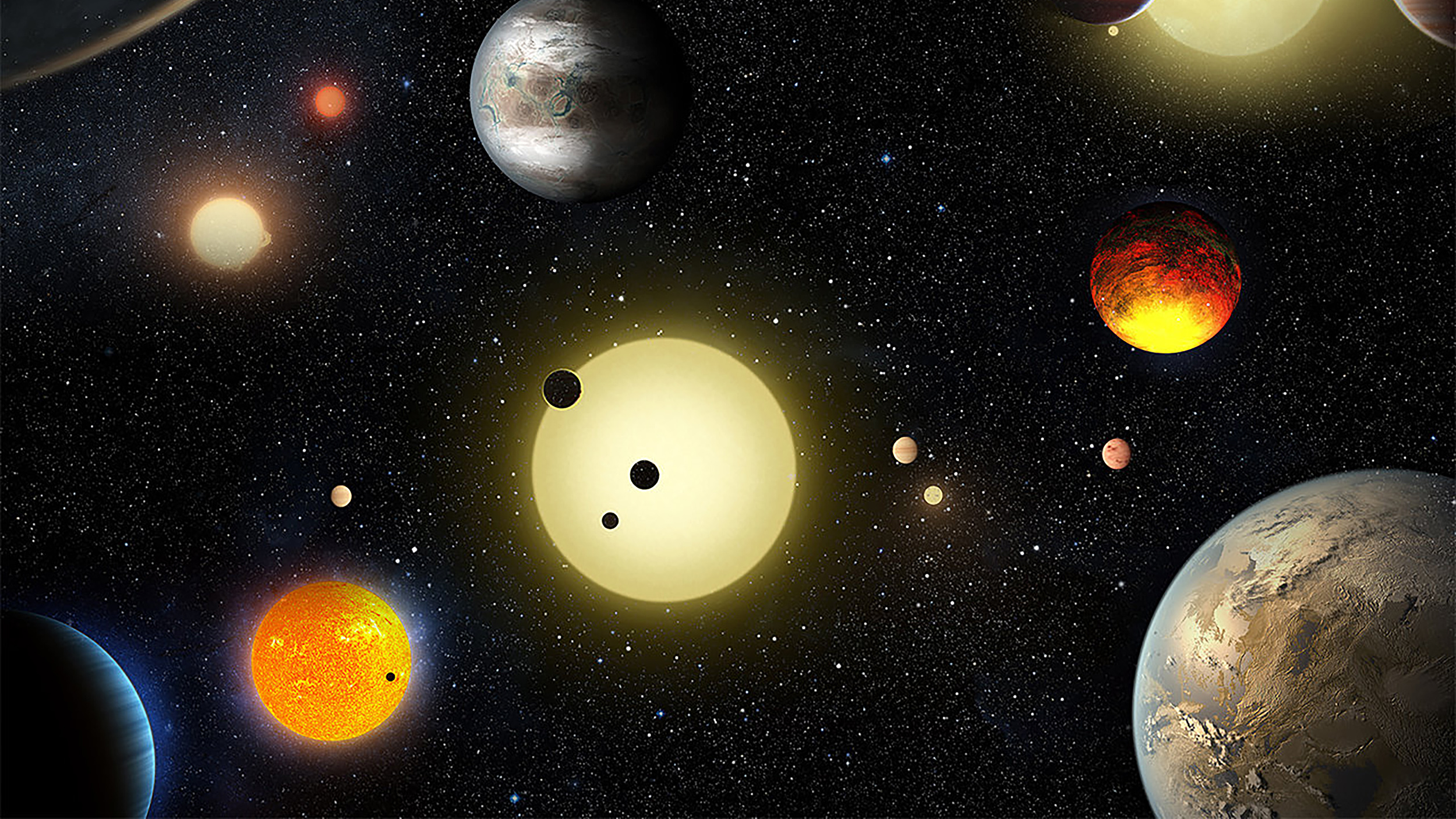

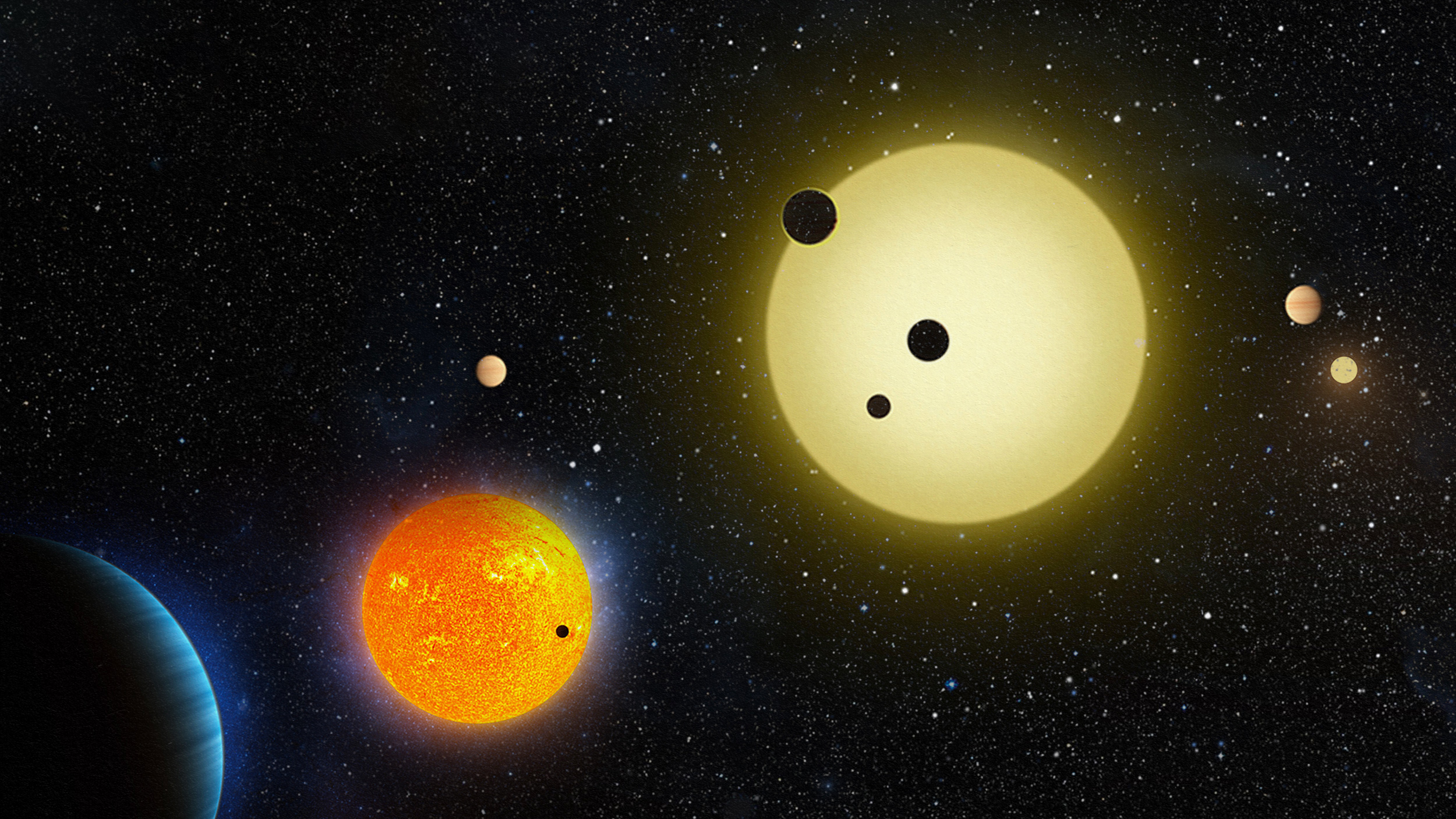

Astronomers have discovered more than 5,000 confirmed exoplanets — very few of which resemble Earth.

Our intuitive understanding of time is very different from a physicist’s understanding of time. How do we reconcile these views?

Two of the answers add a dimension to physics that doesn’t belong there. Maybe we could call it “astrotheology.”

We need a hypothesis that accounts for both the fine-tuning of physics for life but also the arbitrariness and gratuitous suffering we find in the world.

“If we find just one other example of biology out there, then life is not an accident.”

From ancient Greek cosmology to today’s mysteries of dark matter and dark energy, explore the relentless quest to understand the Universe’s invisible forces.

The best answer we have is, “Life is matter with intentionality.”

Finding a tiny planet around bright stars dozens or hundreds of light-years from Earth is extremely difficult.

Scientists may have detected the somewhat smelly chemical dimethyl sulfide on a planet 120 light-years from Earth.

Looking at our planet with post-Copernican eyes has the power to change how we relate to it and each other.

A new book envisions an encounter of minds between the Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges, the physicist Werner Heisenberg, and the philosopher Immanuel Kant.

Life in the supremely vast cosmos is incredibly rare. We need a new vision for our living planet and for ourselves.

We should acknowledge that there are faith-based myths running deep in science’s canon.

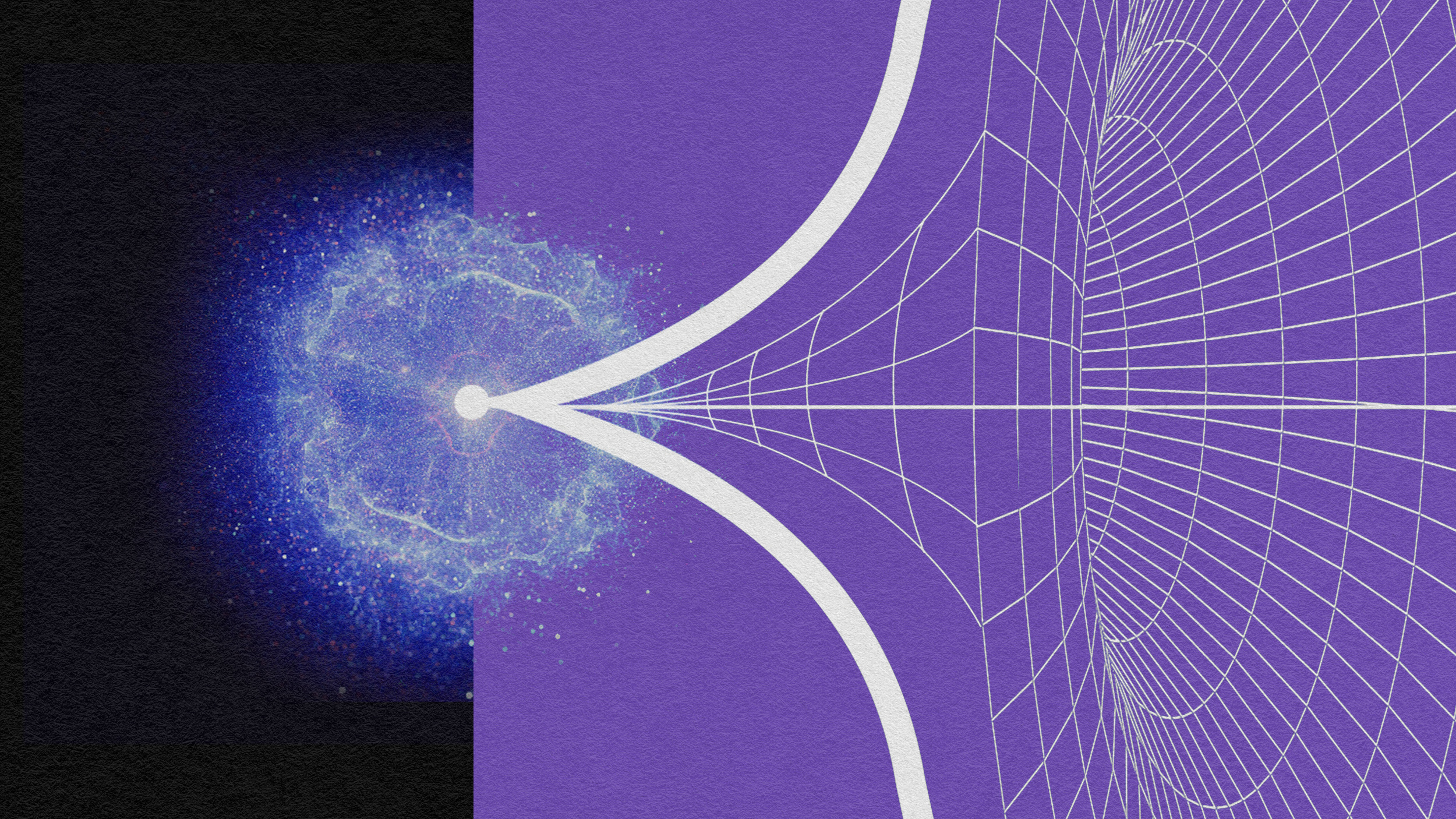

The multiverse pushes beyond the limits of the scientific method. From our vantage point in the Universe, we cannot know if it’s real.

How are we to deal with the quantization of spacetime and gravity?

There is no such thing as a void in the Universe.

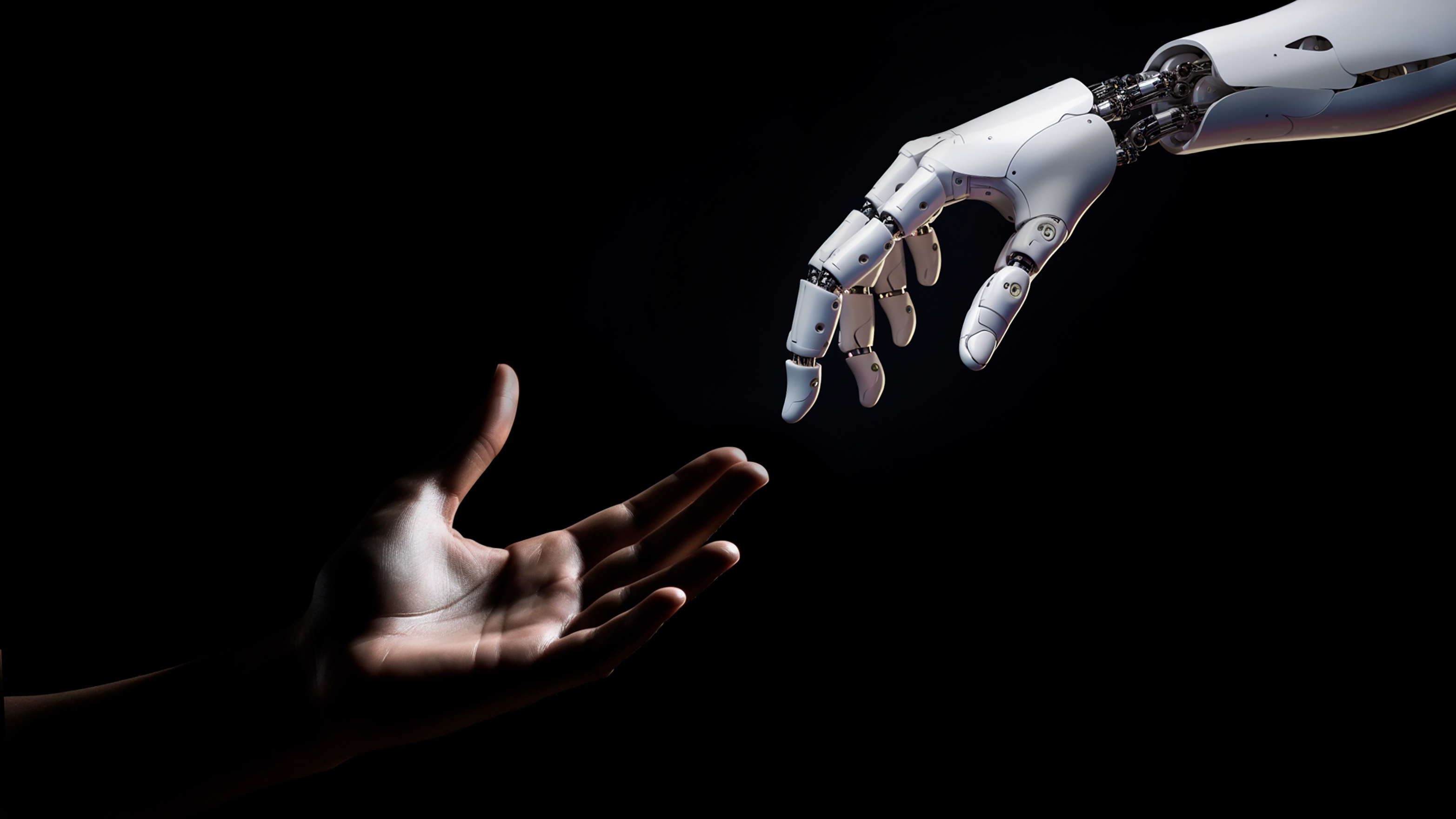

Fear of technology is not new. But we misunderstand its origin. In reality, we don’t fear technology but each other.

Perhaps the whole Universe is the result of a vacuum fluctuation, originating from what we could call quantum nothingness.