No end in sight: Mass exodus of Venezuelan refugees flood into neighboring countries

Image source: Wikimedia Commons

- Millions of Venezuelan refugees are taxing their destination countries’ infrastructures.

- About 4 million Venezuelans have already fled from their home country.

- Countries such as Peru and Ecuador are trying to stem the flow, while Colombia welcomes more in.

Latin America is suffering one of the largest refugee crises in its history. Venezuela’s outpouring of refugees is only second to that of Syria. Already four million Venezuelans have escaped their homeland, the brunt of the exodus started in 2015. A staggering 12 percent of the country’s entire population have already fled.

Running away from a collapsed economy and a repressive government, more than one million Venezuelans have left since the end of 2018. The UN predicts that this number will rise to 5.4 million before the year is through. Other sources project that several hundred thousand to millions more may join the fold by the early 2020s.

Venezuela’s refugee crisis

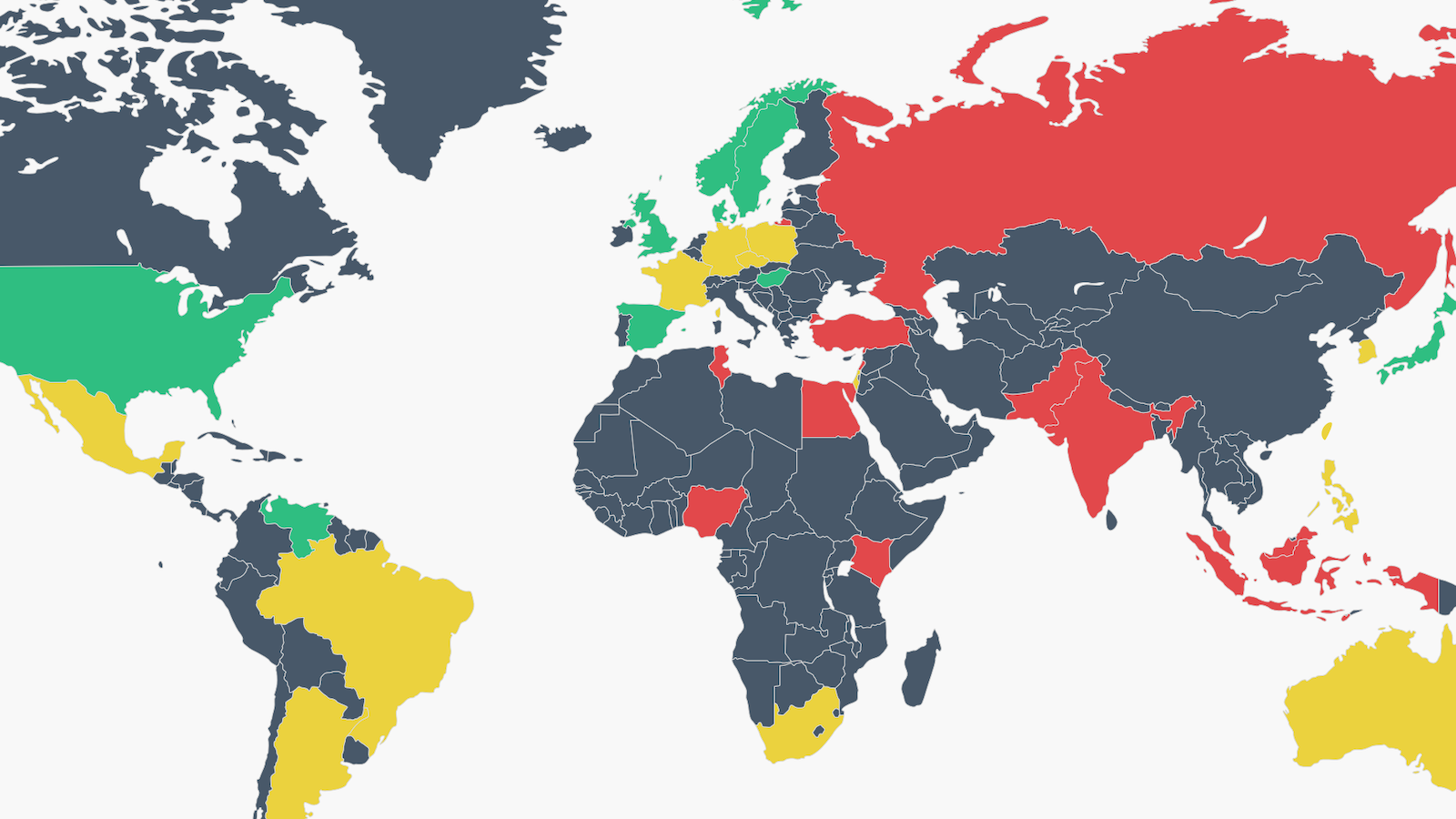

No country has been left unaffected by the impact of Venezuela’s downfall. Colombia, which shares the longest border with Venezuela, at the moment hosts 1.3 million refugees. This is followed by roughly another 800,000 in Peru, 300,000 in Chile, and 260,000 in Ecuador. A number of Caribbean states have a high number of refugees relative to their total population, as well.

Colombia expects to take in up to 3 million refugees by 2021. Ambassador Francisco Santos recently told reporters, “To be very sincere, if it goes to 3 million, we don’t have the money.”

Only a fraction of international assistance has been devoted to the Venezuelan refugee crisis. Indeed, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) need an additional $738 million to assist migrant-receptive countries in both Latin America and the Caribbean region.

The joint UNHCR-IOM special representative for Venezuelan migrants, Eduardo Stein, recently stated, “We are looking at a complex set of needs for the next two years, even if there is a political solution today.”

The UN has repeatedly put out calls for more funding: “Latin American and Caribbean countries are doing their part to respond to this unprecedented crisis, but they cannot be expected to continue doing it without international help,” Stein declared.

Displacement of Venezuelans in Colombia

Millions are roving and crossing borders as the days go by. Some estimate that the exodus could, in all, exceed 8 million people. A number of bordering countries have already begun to tighten their entry requirements and put up further barriers. Ecuador, for instance, upped its requirements — Venezuelans now need to present a passport and a clear criminal record in order to get into the country. So far, both Brazil and Colombia have kept their open border policy.

A majority of the migrants have stayed in the region. Yet, as the crisis continues, these once open destination countries are becoming less welcoming. Dealing with their own problems of slow economic growth, scare jobs, and overtaxed health and education infrastructures, many of these countries can’t support the influx of migrant entrants.

Recent waves of refugees are poorer than those that had come before. Lack of jobs and unstable environments, historically, lead to exploitation and the rise of crime. Colombia with its 1,400-mile border with Venezuela, is now dealing with disorder on one end of their country and a build up of refugees on its southern border, as Peru and Ecuador increasingly turn more Venezuelans away.

Brazil has been systematically relocating migrants to the border state of Roraima, where Venezuelans sometimes have been able to work informal jobs and ease labor shortages. The region’s capital city, Boa Vista, with a population of 400,000, now has more than 50,000 displaced Venezuelans.

Venezuelan migrants gather at the Colombian Border

Photo credit: Juan David Moreno Gallego / Anadolu Agency / Getty Images

As a result of the roiling in the region, there has been a surge of homelessness in many of the towns on the border. “We lost control of the city,” says Teresa Surita, the mayor of Boa Vista.

Colombia’s government officials estimate that 0.5 percent of their GDP goes to providing health care, schooling, and other infrastructural services to Venezuelans. Ecuadoran leaders, who recently went to the IMF for increased financial assistance, estimate that their nation spends about $170 million a year — or .16 percent of its GDP — on health and education for Venezuelan migrants with an exceptional humanitarian visa.

There has also been an increase of negative public sentiment regarding the refugees. Amparo Goyes, a resident of Quito, Ecuador’s capital states, “People used to feel sorry for [Venezuelans], but now there’s fear of crime.”

Politicians and citizens are calling for tighter controls on migrants and restrictions on immigration.

Even so, amidst the changing attitudes and growing crisis, Colombia has been issuing permits that’ll allow 700,000 Venezuelans the right to work and receive public services for a minimum of two years. Politicians in Colombia have even signed a pact that they won’t stir anti-Venezuelan campaigns in the coming elections.

The crisis is Latin America seems to have only begun. Those most touched by the events occurring are urging the global community to assist them in coping with this crisis.